There is a non-trivial chance that former President Donald Trump could be imprisoned before the election — and continue to run for the White House. It’s unprecedented for a former president to be mired in such a legal mess. But what’s less widely known is that there is a precedent for a prominent presidential candidate running for office while locked up in prison.

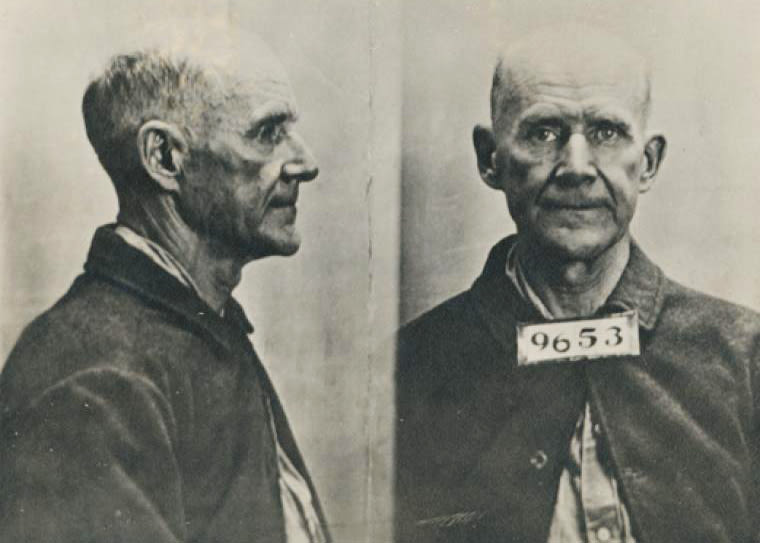

About a century ago, Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs ran for president from prison — and received nearly a million votes, about 3% of the national vote share. Debs’ campaign relished his status as a prisoner; supporters at rallies held picket signs with his prison picture and proudly wore lapel buttons that said, “For President: Convict No. 9653.”

In that respect, Debs’ campaign might appear to parallel Trump’s. The only time Trump has posted on X (formerly known as Twitter) since he was kicked off of the platform in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 insurrection has been to share a photo of his defiant mug shot. Polling indicates that Trump’s base is unfazed by his indictments — and perhaps even more likely to rally on his behalf because of them.

But the similarities end there. Trump’s legal troubles are primarily tied to his attempts to subvert democracy; Debs was imprisoned for anti-war rhetoric on behalf of the working class. Trump commands the support of an authoritarian mass movement; Debs represented a small but influential sector of the far left that called for the expansion of democracy into economic life. While Trump uses his rhetoric to gin up a cult of self, Debs called for “the Christ-like practice of solidarity” with his fellow citizens.

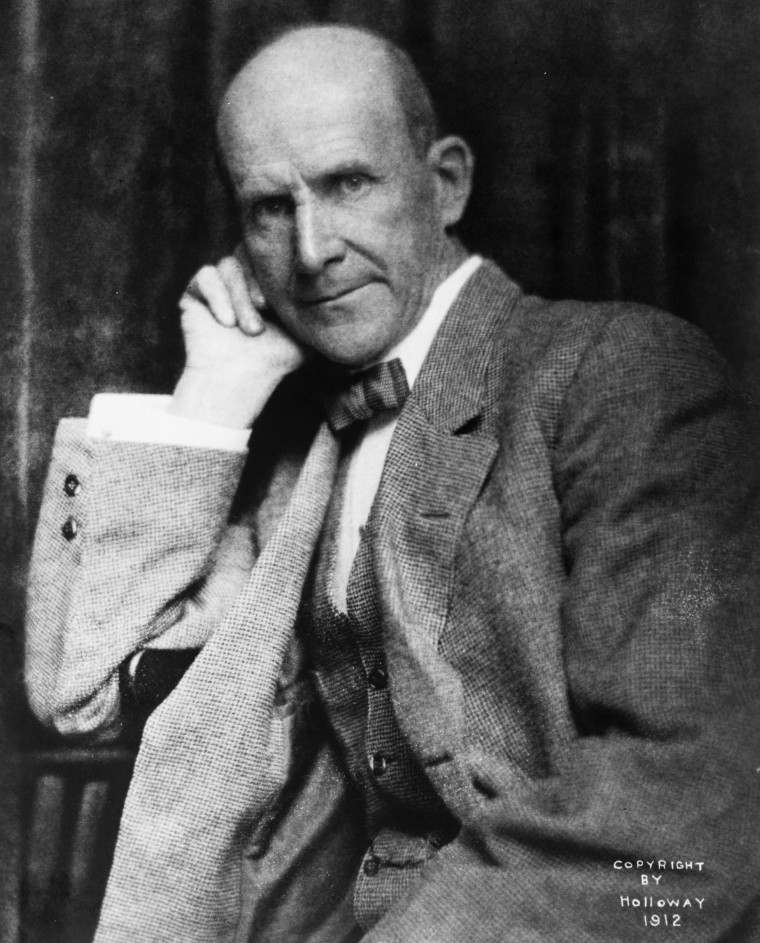

Still, Debs’ run provides a fascinating example of how imprisonment can code politically to the electorate, and the awkward logistics of running for president while stuck in a prison cell. To learn more about his run, I called up Ernest Freeman, a professor at the University of Tennessee and author of “Democracy’s Prisoner: Eugene V. Debs, the Great War, and the Right to Dissent.” Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Zeeshan Aleem: Who was Eugene Debs, and how was this man able to secure a full 3% of the vote while in prison?

Ernest Freeberg: Eugene Debs was one of the founders and the longtime leader of the Socialist Party in the United States. He came up through the labor movement and first went to prison in 1895 for being the leader of the American railway unions in the Pullman Strike, the largest strike in the 19th century. The fact that he was put in jail for leading that strike led him to the conclusion that the two major political parties were both in the hands of what he would consider to be the corporate plutocracy. He believed that the only way forward was to convince workers to vote in their own interests — and that would be embodied in the Socialist Party platform.

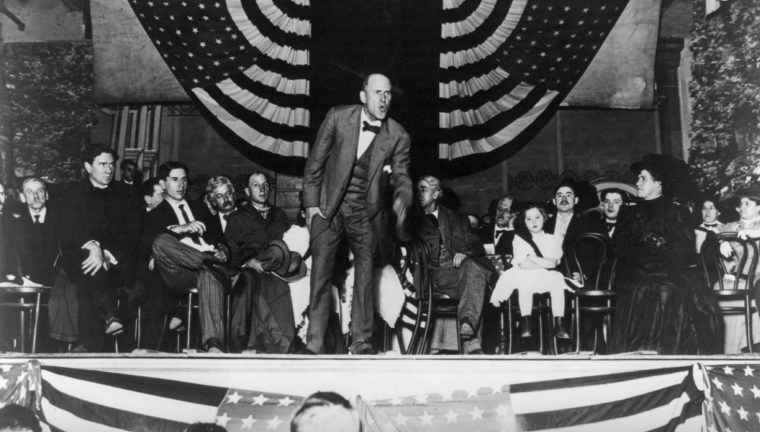

He was really a charismatic speaker, who barnstormed across the country and made his fifth run for president as leader of the Socialist Party in 1920. Even though the Socialists were not ever close to winning a presidential campaign, they had quite a number of state-level and city-level offices. His high watermark was 6% of the presidential vote in 1912. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, called Debs one of America’s “most undesirable citizens,” an apostle of “bloodshed, anarchy, and riot.” Roosevelt also urged his fellow progressives to borrow some of the moderate parts of the Socialist message in order to head off the really revolutionary parts. Some ideas — such as old age pensions, support for health benefits, women’s suffrage, a ban on child labor, and state support for kindergarten — were part of the Socialist Party platform long before they became adopted by the main parties.

What was unique about Debs was that he was able to take what many considered to be a radical, foreign idea like socialism and present it in the American vein.

Ernest Freeberg

What was unique about Debs was that he was able to take what many considered to be a radical, foreign idea like socialism and present it in the American vein. He was comfortable talking about socialism in the context of the Declaration of Independence and Tom Paine and Walt Whitman and John Brown. His argument was: We completed the war against chattel slavery, and the next step was wage slavery.

Can you give us some more context on why he was imprisoned?

Freeberg: When the war broke out in 1914, the vast majority of Americans from all different political persuasions favored American neutrality. The gradual escalation of the war eventually led Woodrow Wilson to enter the war in 1917, and there had to be a major draft right away. The government decided that it would do two things: First, it would seize the loudest microphone in the marketplace of ideas by creating a massive propaganda campaign to stir up hatred of the Germans and to rally support for the allies. Second, Congress very quickly passed the Espionage Act, which made it illegal to give comfort to the enemy, essentially. This law was not used to prosecute spies, but in fact became a powerful weapon for silencing dissent.

Debs was strongly anti-war, and he was well aware that if he went onto the stump and gave a speech about the war that he would, along with his fellow comrades, end up going to jail. In June of 1918 he gave a speech at a Socialist picnic in Canton, Ohio, knowing that there were government agents in the audience who were taking down his every word. He says things like, "You need at this time especially to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder," making the argument he’s made all along, which is that this was, as the saying goes, “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

Debs was put on trial in Cleveland, and he used that as an opportunity to speak against the war again and to defend his right to free speech. The government argued that what he was really doing at that Socialist picnic was trying to incite young men in the crowd to resist the draft. One of the long-standing exceptions to First Amendment rights is that you’re not allowed to use speech to incite others to crime. Nobody in the audience was found to not have their draft registration; there was no evidence that anybody was moved to not participate in the draft because of hearing Debs speak. But given the way the law was applied in 1918, he was very quickly convicted.

Debs wasn’t the only one convicted — over 1,200 socialists, anarchists, religious pacifists, and some people who just said some cranky thing about the war effort in the wrong place were prosecuted, and many were jailed. Few people knew or cared about most of these people, but Debs was the visible one, a significant voice in American political life for decades. The sight of him in prison garb galvanized many who decided the government had gone too far in silencing dissent. So an amnesty movement around these prisoners centered around getting him out of prison. Part of the amnesty movement strategy to get Debs out of prison — or at least to help people remember that he was in jail — was to nominate him for president in 1920. While the Socialist Party was in disarray in 1920, thanks in large part to government persecution, almost a million Americans voted for Debs, considering it a protest vote for freedom of speech.

How much did his imprisonment for his beliefs play a role in inspiring his fifth and final run?

Freeberg: The imprisonment was central to deciding to run him again. At this point, the Socialist Party is largely shattered. It’s been split by some who feel like the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia is the way forward and that the idea of convincing workers to vote is a dead end. The government has also rounded up many Socialist leaders in jail. And so one thing they hope to pull them together is uniting around Eugene Debs as their leader. What they’re counting on is turning this into a chance for people to vote in a protest vote against the Wilson administration’s persecution of free speech.

The attorney general and Woodrow Wilson are inundated with letters from people writing to say, ‘Look, I’m not a socialist, and I’m a great believer in the war effort. But we’ve gone off the rails to be putting people in jail in this way.’ Many of them are the ones who end up voting for Debs as a protest vote.

How did he actually campaign while he was in prison?

Freeberg: The government was very confused about how to handle this. They ultimately agreed to allow him to write a 500-word letter to the newspaper, once a week, during the campaign season. These were published at the discretion of the press. Most of what he would consider to be the capitalist-controlled press was not interested in running his opinions on anything, so they didn’t appear in a lot of places. You could find it in the socialist press and independent press here and there, but an awful lot of that was bankrupted by the Espionage Act. So he didn’t get the word out that much.

It’s one of the great forgotten mass protest movements, and also one of the great forgotten free speech movements in our history — this three-year campaign to get Debs out of prison.

Ernest Freeberg

In prison, he was allowed to have visitors, and he would smuggle messages out — usually messages designed to show complete defiance of the government. When it was suggested that maybe Wilson would pardon him if he apologized, he would say, 'Wilson is the one who belongs in prison, not me.' He wasn’t going to yield at all in order to try to win a pardon.

It’s one of the great forgotten mass protest movements, and also one of the great forgotten free speech movements in our history — this three-year campaign to get Debs out of prison. If you look at the people who signed on to this, it’s really a who’s who of writers and thinkers of the day: Helen Keller, Carl Sandburg and H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw, and the list goes on. People enlisted in this regardless of whether they were themselves socialists.

Was Debs’ embrace of his identity as a prisoner helpful for garnering votes?

Freeberg: It certainly was; it’s hard to imagine any other candidates in the Socialist ranks at that point getting anything like the attention that Debs did running from prison. So at least in terms of raising the visibility of the Socialist message (limited as it was), I’m sure that that helped. But for many people, the vote was really not about whether or not socialist policies should be adopted, but rather as a protest vote about free speech. And the Socialists tended to sell it that way, to a wider audience. They didn’t spend a lot of time trying to advocate in this campaign for their ideas about state ownership of the means of production, they focused much more on the outrage of what had happened to Socialists, with Debs being the poster boy for that.

What was Debs’ experience in prison?

Debs considered prison to be an institution of class warfare, and believed that he could be just as good a Socialist leader in prison as he could be out on the stump. He endeared himself to every warden he ever met; they ended up sneaking him out of prison to have breakfast with their family and taking him on picnics, and becoming lifelong friends. They consulted with Debs about how to improve prison conditions. Debs got assigned to the prison hospital in Atlanta, where he spent a lot of time helping people who were dealing with drug addiction and sexually transmitted diseases and suffering and dying, and he would write letters for them. People all around the world were sending Debs candy and tobacco and books, and he would keep little of it for himself and pass it around to everybody. His wardens would say things like 'he’s the most Christ-like person I’ve ever met.' When Debs got out of prison, he wrote a book called “Walls and Bars,” which is a series of essays about prison reform. He made the most of his time in prison.

It’s hard to imagine two politicians more different than Debs and Trump. But in light of the emerging comparisons, maybe you can help illuminate how so?

They’re different in terms of the success of Trump’s following. Both of them are, on some fundamental level, populists who claim that the enemy is the powers-that-be in Washington. The Socialist Party developed a far more concrete, detailed program for actually reconstructing the way American democracy and the American economy would work. So they’re pulling on the same general anxiety about capitalism, but their blueprint for what to do about it is directly opposite.

On the issue of labor, for example, for Debs the key is for working people to organize and to think of themselves as voting for their class interest, and to organize at the site of the workplace to demand more access to the goods that are being produced by American abundance. I have a hard time really understanding what Trump is actually offering, aside from nativism — and at this point not even that. Mostly, all I’m hearing is his claim that he’s won the 2020 election.

What do you think is valuable about reckoning with Debs’ legacy today?

Freeberg: There was a time in our history when our conception about the range of political possibilities was much wider, when the Socialist Party was active and a meaningful voice in the conversation. Many of their ideas about reform were adopted and absorbed, and are now considered to be a commonplace part of the fabric of our society (the other parts being too radical, the ideas about state control of the means of production). But it forced the conversation in directions that, I think, made grappling with the problems of the day much richer for society than we have now.

One of the drawbacks of the Red Scare — the first one that shut down the Socialists in the 1920s, not to mention the 1950s — is that it made that socialist tradition seem like an alien force in American life, rather than recognizing that there was this long, radical socialist tradition that very much emerges out of and is part of the American democratic tradition.