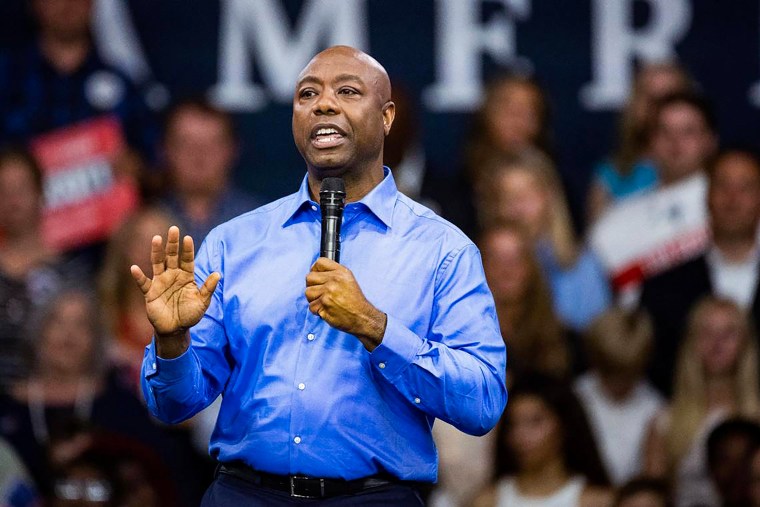

Four days after a Republican primary debate in Miami where he was “long-winded, off-topic and boring,” Sen. Scott Tim Scott, R-S.C., announced Sunday that he was suspending his campaign for president. “I think the voters, who are the most remarkable people on the planet, have been really clear that they’re telling me: not now,” he told former GOP Rep. Trey Gowdy, now a Fox News host.

Is there a Black Republican candidate who can be honest about his or her experiences as a Black person while campaigning for the country's highest office?

When, if ever, will it be the time for the Black Republican presidential candidate? Can there ever be one who doesn’t have to deny the existence (or at least the impact) of racism in a run for the White House? Who doesn’t feel compelled — as Scott so often did, and as Ben Carson and Herman Cain so often did — to portray other Black people as broken?

“I don’t believe racism in this country today holds anybody back in a big way,” Cain said in 2011. In 2015, Carson, who was in Ferguson, Missouri, the year after a white police officer shot and killed Black teenager Michael Brown, said that he wasn’t sure whether there had been wrongful targeting of Black people but that he did see a problem with safety-net programs, saying, “We need to be looking at all the factors that have kept the Black community in a very dependent position for decades.”

Is there a Black Republican candidate who can be honest about his or her experiences as a Black person while campaigning for the country's highest office? Or is dishonesty about race in America the price of admission?

In July 2016, the week after a police officer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, shot and killed Alton Sterling and a police officer in St. Anthony, Minnesota, shot and killed Philando Castile, Scott gave a speech on the floor of the Senate. He told the story of how, in one year of life as an elected official, police had pulled him over seven times. Once he was accused of driving a stolen car. His brother, a command sergeant major in the Army, had been pulled over and accused of the same. He told the story of one of his staffers, a 30-year-old Black man, who was “pulled over so many times here in D.C. for absolutely no reason other than driving a nice car.” And he told the story of a supervisor with the Capitol Police who called to apologize after an officer disregarded Scott’s congressional pin and demanded ID. “That is at least the third phone call that I have received from a supervisor or the chief of police since I have been in the Senate,” said Scott.

Scott was no less of a conservative then. But rather than deny racism’s existence, he was clear-eyed about what he’d observed and, given his party affiliation, rather brave.

“Was I speeding sometimes? Sure,” Scott said about his experience being pulled over seven times. “But the vast majority of the time I was pulled over for driving a new car in the wrong neighborhood or something else just as trivial.” Most important, he said, “I do not know many African American men who do not have a very similar story to tell no matter their profession. No matter their income, no matter their disposition in life.”

After George Floyd’s murder, Scott was one of the lawmakers who was working on a police reform bill. Unfortunately, no bill ever came together. And since Scott entered the presidential race, that honesty he showed on the Senate floor has gone missing.

Appearing on ABC’s “The View” in June, Scott was asked about his stated belief that systemic racism doesn’t exist.

“I said America is not a racist country,” he said. “Because it’s not.”

Scott isn’t a rarity. There’s an untold number of socially conservative Black people, even fiscally conservative Black people

Based on his general political views, Scott isn’t a rarity. There’s an untold number of socially conservative Black people, even fiscally conservative Black people. They are not islands to themselves but regular Black people, living in regular Black communities everywhere.

What keeps the politically inclined among them from running as Republicans? Most likely the realization that, in order to fully ingratiate themselves with the GOP, they’d have to do as Scott did during his failed presidential run: pretend that racism is nothing but the figment of the Black person’s (or the big-government liberal’s) imagination.

Rich Lowry, editor of the conservative National Review, praised Scott’s appearance on “The View” and shared to social media a video clip of Scott arguing that racism isn’t holding Black people back and that “progress in America is palpable.” In fact, Scott’s remarks on “The View” seemed designed to excite those running conservative media.

But in the same way that Scott’s July 2016 Senate speech revealed his frustrations with racism, so did remarks he made to The Washington Post two months ago. The Post was writing about reports that wealthy GOP donors didn’t want to give to an unmarried candidate such as Scott. But he perceived something more sinister. “It’s like a different form of discrimination or bias,” Scott told the newspaper. “You can’t say I’m Black, because that would be terrible, so find something else that you can attack.”

He had to have known — right? — that donors who didn’t want to give to him because he’s single surely wouldn’t be convinced to give to him after he accused them of having an issue with his race. It’s telling, then, that he said what he said anyway.

This Republican nomination process was over before it began, but that remark to the Post may have signaled the moment when Scott knew he was out: the moment, that is, he refused to be the racism denier he thought his presidential aspirations required.