In 2023, Taylor Swift achieved total pop music ubiquity. Her Eras Tour became the highest-grossing tour of all time. She was named Time’s Person of the Year. She won album of the year at the Grammys. She became a billionaire. And her whirlwind romance with Kansas City football star Travis Kelce launched a hundred Fox News conspiracy theories.

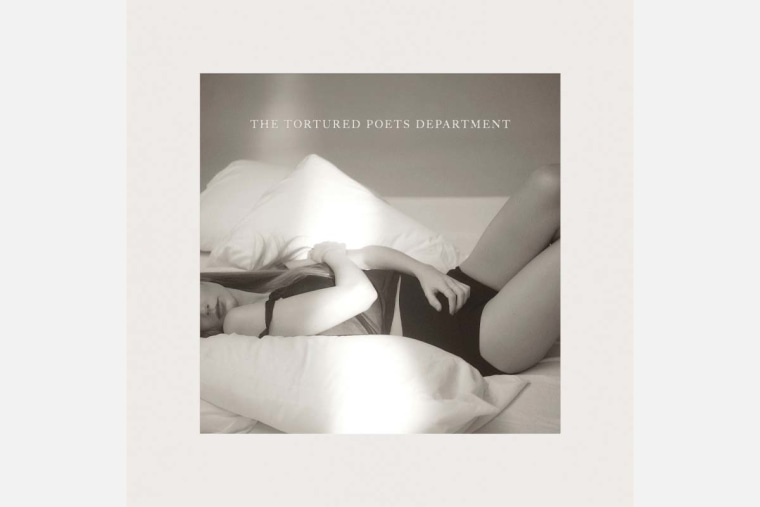

Amid this chaos and success, on Friday Swift released her 6th project in three years, “The Tortured Poets Department.” On one hand, the project is proof of her business acumen: iHeartRadio rebranded Friday “iHeartTaylor” and streamed the entire album as soon as it came out; Instagram designed a new feature specifically for her to tease the project. But Swift positions the album as an emotional salve. These were songs she “needed to make … more than any of my albums that I ever made.” Finished on tour amid the end of a six-year-relationship, there was certainly plenty for her to parse. But the first half of the (surprise double) album especially is too lyrically broad to feel especially poignant. Swift’s most intense feelings come across when she talks about her career and the scrutiny she faces as a public figure. But ultimately “The Tortured Poets Department” feels like a portrait of heartbreak that often avoids the details of what made the love so special and the separation so painful, and a criticism of celebrity that feels as much a product as it is a musical offering.

“The Tortured Poets Department” feels like a portrait of heartbreak that often avoids the details of what made the love so special and the separation so painful.

The synth-pop arrangements on the original 17 songs sound a lot like “Midnights,” and as a result are too often homogenous. Choruses tend to echo and drift rather than build, and a general glossy smoothness tamps down Swift’s vocals. Lyrically, Swift skirts the confessionalism or candor that might give these songs emotional urgency. On “Down Bad,” she reveals, “For a moment I knew cosmic love,” only to follow it up with “Now I’m down bad crying at the gym.” On “Alchemy” she begins, “This happens once every few lifetimes” before saying “These chemicals hit me like white wine.” These are references that feel engineered for widespread appeal rather than personalized storytelling.

At her best, Swift is a master of synecdoche. She outlines a narrative full of tension, misunderstanding, or regret and then fills in the gaps with tiny memories that evoke entire worlds outside the frame. But here again, the first half of “Tortured Poets” underwhelms, as that framing largely slips away. There are very few stories, and more statements of feeling. The random details she provides serve little purpose. Her mention of Charlie Puth (“You smokеd, then ate seven bars of chocolate/ We declared Charlie Puth should be a bigger artist”) on the title track tells us nothing about her and an ex’s dynamic except that they shared surprisingly bad music tastes. The same song uses the device of a typewriter to point to an ex’s pretentious taste, but tells us nothing about how that character trait made her feel or how it impacted their dynamic.

On earlier albums, Swift released her worst songs as singles as a kind of red herring for the tone of the album. (“ME!” was a single on the album that had “Cruel Summer,” for example.) With “Midnights” and “The Tortured Poets Department” she does this but on a bigger scale, following both pop albums with more introspective, delicate, acoustic tracks released a few hours later. These songs, mostly produced by Aaron Dessner and written in Swift's “quill pen” literary prose style, are infinitely more textured, imaginative, and intriguing. On “So High School,” Swift’s gauzy falsetto meshes beautifully with a gnashing ‘90s guitar line, seamlessly relaying a nostalgic sense of euphoria. On gentle piano ballad “Robin,” Swift observes a child’s sense of innocence with care and poignant yearning. And the finger plucked guitar on “I Look In People’s Windows” beautifully expresses a sense of hope that a glimpse of a lost love can spark.

These songs engage in the world-building and storytelling that is Swift’s forte. But they still never quite reach the self-interrogation, empathy, or wisdom of “folklore” and “evermore,” which are the most stylistically similar releases in her catalog. There is a lingering sense of remove here; ornate language papering over a lack of intimacy and complexity.

“Prophesy” has one of the most interesting conceits on the record. Swift positions herself as both a noble and desperate woman in her pursuit of love above all else. But the specter of the titular prophecy is so grand and foreboding, yet largely unexplained, that it overshadows her finer emotional points. “How Did It End” shares a similarly compelling angle on heartbreak: Swift recounts the experience of telling her friends about a breakup and imagines how they process the news. But the language she chooses is clunky (“We were blind to unforeseen circumstances/ We learn the right steps to differеnt dances/ And fell victim to interlopеr’s glances/Lost the game of chance, what are the chances?”) that it is genuinely difficult to access the emotion behind the words.

The most intense writing on the album is about her relationship to fame and work. “I Hate It Here” is an urgent lament about needing to escape. Her imagination runs wild as she dreams up secluded lunar valleys and secret gardens. Here, finally, the romantic prose fit well with the intention of the song. On “Cassandra,” she (presumably) alludes to her feud with Kanye West, ruefully asserting she was right about her onetime interrupter — even if she was initially criticized for her warnings. And on “But Daddy I Love Him,” she resents fans “sanctimoniously performing soliloquies I’ll never see” about whom she chooses to date.

Given the year she’s had, the album’s consistent underdog mentality is less than satisfying. It is a little jarring to hear Swift sing a song like “thanK you aIMee” at this moment in her career. The track, which sarcastically thanks a detractor for motivating her to achieve more, is essentially a remake of 2010’s “Mean,” which promises a critic that he’s going to be stuck in a boring life while she goes on to live in a “big ole city.” It was a childish but understandable conceit then, when she was 21. Today, she may be the most powerful celebrity on the planet.

As it stands, Swift mostly sidesteps discussions about how she cultivates fame and how her art — this album — is a means to that end. But she concludes the album with a moving description of what her own music means to her. Swift details a relationship from her youth that left her so devastated she had to sleep in her mother’s bed and eat cereal. The process of writing a song about that breakup allowed her to let go of the trauma. At the end, she offers that same song to us as a gift, saying, “Now and then I reread the manuscript/But the story isn’t mine anymore.” To make music that feels like art and not a product, Swift needs to prioritize consistently writing with this much clarity, specificity, and honesty, knowing that it will then resonate outward.