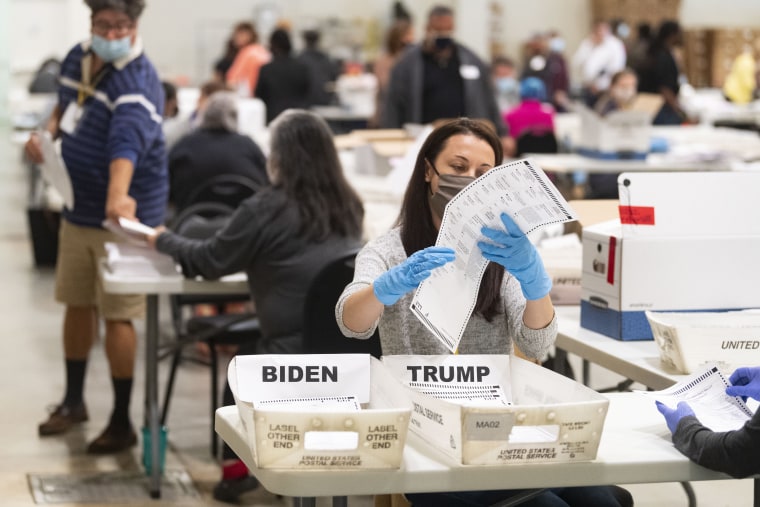

“A functioning democracy requires that the public servants who administer our elections are able to do their jobs without fearing for their lives,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said in a statement Thursday. That statement accompanied the Justice Department’s announcement that federal prosecutors in Georgia and Arizona had obtained two separate guilty pleas in two separate cases from those who made criminal threats against election workers. According to the Justice Department, its Election Threats Task Force has led to charges in 14 cases and nine convictions related to threats against election workers.

According to the Justice Department, its Election Threats Task Force has led to 14 charges and nine convictions related to threats against election workers.

That’s not bad for a task force that was launched two years ago in response to the sharp spike in hostile threats to election workers after the 2020 presidential election. Not bad, but not great, either.

More than 1,000 communications reported by election officials have been assessed by the Justice Department task force since its inception. The Justice Department found about 11% of the reported messages met established criteria for opening federal criminal cases. That means the Justice Department initiated about 110 investigations into threats aimed at election workers — who include volunteers, as well as career public servants and elected officials. In that context, a mere 14 cases’ being charged and nine convictions in two years isn’t cause for celebration. We’re talking not only about threats to individuals; such threats undermine our elections process, the cornerstone of our democracy.

The two guilty pleas the Justice Department announced Thursday involved defendants charged with threatening workers in other states. In the Georgia case, a Texas man pleaded guilty to making violent threats on social media that targeted state officials, an election worker and local police. In the Arizona case, an Ohio man pleaded guilty to threatening to kill an election overseer inside the Arizona secretary of state’s office. Also, on Aug. 28 in Arizona, an Iowa man was sentenced to 2½ years in prison for communicating threats to a Maricopa County Board of Supervisors election official, as well as to the then-state attorney general.

According to the Justice Department, almost 60% of the threats it has investigated have targeted election workers in seven key swing states, but many of the defendants accused of being responsible lived elsewhere. That means the threat isn’t isolated; it’s nationwide. That means there needs to be a more assertive and proactive national response by federal law enforcement officials and a similarly assertive response by officials at the county and state levels.

An all-hands-on deck approach is needed if we’re to secure the 2024 elections. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, an April survey revealed 45% of election workers had safety concerns for their peer group in upcoming elections. Swift investigations, prioritized prosecutions and sentences that reflect the gravity of the problem are essential for at least two reasons.

First, consequences and accountability usually have a deterrent effect on future bad conduct. For example, the more than 1,000 arrests related to the Jan. 6, 2021, breach of the U.S. Capitol and long sentences for organizers are generally considered to have had a deterrent effect on those contemplating similar acts. The same would be true for those thinking about threatening election workers.

Election officials who’ve expressed concerns about threats need the assurance that threats against them will be met with the full force of the government.

Second, those election officials who’ve expressed concerns about threats need the assurance that threats against them will be met with the full force of the government. That kind of confidence doesn’t come from promises alone but from tangible prosecutive results. If election workers are worried about threats from the criminal element, they may decline to work the polls, leaving us with poll workers who aren’t as worried because they’re aligned with those making the threats.

Further, the people threatening the people who make sure our elections go smoothly can’t be deterred if they don’t hear about the consequences levied upon others. Similarly, election workers can’t feel assured if they don’t hear about criminal accountability for those behind the threats. That kind of transparency and messaging doesn’t happen with nine convictions and a media update every two years. We need more publicity surrounding arrests and prosecutions — and not just from the feds, but also from county and state officials.

Federal elections are run by the states, but you wouldn’t know that from the near absence of efforts by those states to protect the people who run those elections. In fact, there seems to be a disturbing lack of state-level attention to these threats. In October, the Center for American Progress, an independent, nonpartisan policy institute, wrote of complaints from election workers that “the threats and harassment they’ve reported have not been taken seriously by local law enforcement.” If election workers feel that their concerns are minimized, they’ll most likely stop reporting them. In November 2021, Reuters wrote about the threats against election officials that were never acted upon by state prosecutors. Reuters described this inaction as “the paralysis of law enforcement in responding to this extraordinary assault on the nation’s electoral machinery.”

The high-threat environment in the country might have factored into Garland’s decision to publicly denounce threats against election workers and to summarize his task force’s results. Judges, jurors, witnesses and prosecutors are facing unprecedented threats in connection with four indictments against former President Donald Trump. He’s right when he says our democracy requires that election workers must be able to “do their jobs without fearing for their lives.”

Counties and states need to figure out a coherent plan to secure election workers, and the Justice Department needs to step up its efforts.

Law enforcement officials and prosecutors need to be careful to make the distinctions between threats and free speech when they’re making decisions related to investigating and charging threats. They also need to make sure their strategies about whether to investigate or charge aren’t driven by political factors; that has no place in law enforcement strategies. But the counties and states need to figure out a coherent plan to secure election workers, and the Justice Department needs to step up its efforts.

We need such a two-pronged federal and state approach lest the only citizens who feel they can safely exercise free speech are the ones who threatened everybody else into silence.