Former President Donald Trump stands indicted in Georgia state court in a case with 19 defendants for his alleged efforts to subvert the 2020 presidential election in Georgia. Trump has made it clear that he doesn’t want a speedy trial in any of the four cases in which he is criminally charged, but some of his co-defendants in Georgia seem to be champing at the bit to get to trial as soon as possible. And Thursday, after there were no objections from Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee set an Oct. 23 trial date for co-defendant Kenneth Chesebro, an attorney.

Trump doesn’t want a speedy trial in any of the four cases in which he is charged, but some of his co-defendants in Georgia seem to be champing at the bit.

If that first Georgia trial begins in just two months without Trump himself as one of the defendants on trial, it could spell real trouble for Trump, at least in the court of public opinion.

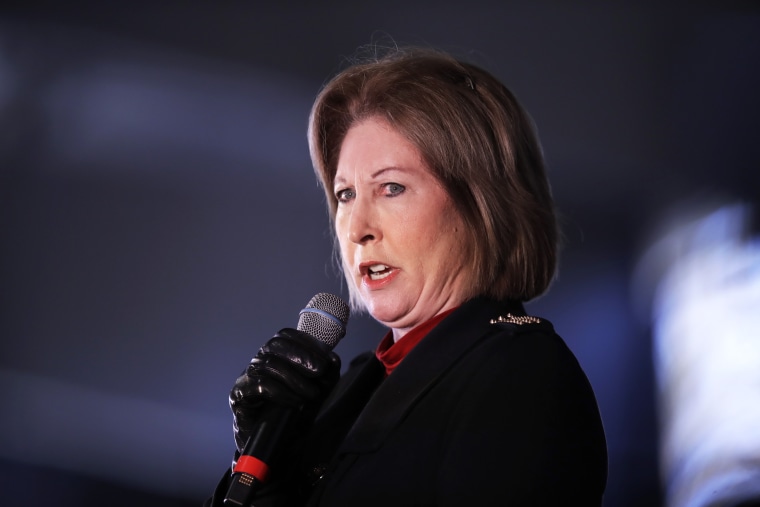

In addition to Chesebro, another attorney, Sidney Powell, has also demanded a speedy trial. Judge McAfee is likely to add Powell to the same Oct. 23 trial date, together with any other co-defendants who make speedy trial demands. In a motion Tuesday, Willis said, "The State maintains its position that severance is improper at this juncture and that all Defendants should be tried together."

In large conspiracy cases, it’s entirely usual to batch defendants together and try them in a series of cases. For example, as a federal prosecutor, I was involved in a large-scale RICO case in Washington, D.C., in which more than two dozen defendants were indicted. After all but 13 pleaded guilty, we batched the defendants into three trials: six defendants in the first trial, six in the second and the last defendant in the third trial.

Two things tend to happen when you prosecute co-conspirators in a series of separate trials, one of which could hurt Trump and the second of which could help him.

When Chesebro and Powell go to trial, their defense attorneys undoubtedly will attack every piece of evidence that tends to incriminate them. But if Trump’s not a part of that first trial, their attorneys may choose not to challenge any of the evidence that incriminates Trump or other alleged co-conspirators. In fact, their attorneys may even embrace and highlight to the jury the evidence that incriminates, say, Trump, Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman and others.

It’s called the “empty-chair defense,” and it can be extremely damaging in the court of public opinion, even if it isn’t all that impactful in a court of law in future trials. Of course, because Georgia allows cameras in the courtroom, this trial could give the viewing public the first chance to see the evidence prosecutors have. That’s why that first trial could have such a significant impact on public opinion.

Attorneys for Chesebro and Powell may argue that Trump, Giuliani, Eastman and others are the real bad actors. It’s easy to imagine an argument from them that their clients were just carrying out the expressed desires of Trump and that he is the one who ultimately bears responsibility for anything that may have crossed legal lines.

More directly, Chesebro may try to portray Eastman as the true architect of the “alternate elector theory.” He may contend that he was just following the advice and guidance of Eastman, a constitutional scholar who was then a professor at the Chapman University Fowler School of Law, that Eastman assured him that the alternate elector theory was on sound legal footing and that he had every reason to believe him.

Simultaneously, Powell’s lawyers might argue that Giuliani assured Powell that he had uncovered lots of evidence of actual fraud in the 2020 election and that she was foolish enough to believe him but that it’s Giuliani who should be held accountable and not her.

Of course, in what would be bad news for the former president, both defense teams could choose to argue that the single most blameworthy culprit, the Svengali who ensnared us all in his web of corruption, is Trump. I have seen such “empty chair” arguments resonate with jurors.

Not going first provides opportunities to impeach witnesses who’ve testified in previous trials.

On the other side of the coin, going second or even later in a series of trials provides significant benefits to those co-defendants. If Chesebro and Powell go first, I can pretty much guarantee that defense attorneys for the 17 other co-defendants will attend every day of the trial. They’ll get a bird’s-eye view of the state’s evidence, hear the testimony of every witness, see each piece of documentary evidence and make note of how prosecutors weave the story together for the jury. Thus, they will be better prepared to defend their clients.

Not going first also provides opportunities to impeach witnesses who’ve testified in previous trials. If a witness is asked to tell a story — in the form of testimony at trial — and then that same witness is asked to tell the story again six months or a year later, the story will be somewhat different. That’s human nature. The witness may choose different words or forget things.

When that inevitably happens, defense attorneys will highlight the inconsistencies and ask some version of “Were you lying then, or are you lying now?” (which, technically, is an objectionable question). To be sure, prosecutors have ways to deal with such challenges, but when a series of trials leads to witnesses’ having to testify multiple times about the same facts, in my experience, that tends to favor the defense more than the prosecution.

If the October trial date holds, we will soon see whether Trump’s decision to let others test the strength and quality of Willis’ evidence works to his advantage or his disadvantage, in the courtroom and in the court of public opinion.