We’re nearing the end of Black History Month, and with it, the end of this iteration of "Black History, Uncensored," our series focused on Black writers targeted by conservative bans.

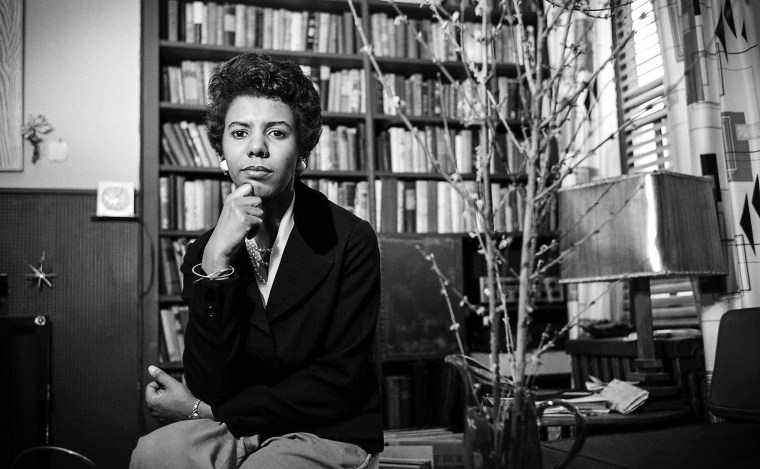

From the outset, I didn't want to confine this series to book authors, because doing so would ignore Black creators whose work didn’t quite fit that form. Creators like Lorraine Hansberry, the famed playwright behind “A Raisin in the Sun."

Hansberry strayed from her middle-class parents’ center-right leanings as a teenager and left Chicago for New York City, where she pursued her writing career and activism. "A Raisin in the Sun" debuted in 1959, making her the first Black woman to have a show produced on Broadway. The play was somewhat autobiographical for Hansberry, telling the story of a Black family who struggles to gain a toehold in middle-class America.

As Blair McClendon wrote for The New Yorker in January 2022:

Hansberry was not raised to be a radical. She was born in Chicago in 1930, the child of an illustrious family that was well regarded in business and academic circles. Lorraine’s father, Carl Augustus Hansberry, was a real-estate speculator and a proud race man. When Lorraine was seven years old, the family bought a house in a mostly white neighborhood. Faced with eviction by the local property owners association, Carl fought against racially restrictive housing covenants in court.

But as we’ll see in Monday’s featured work, the limitations of that victory contributed to Hansberry’s political radicalism.

“The Black Revolution and the White Backlash," Hansberry’s speech at a 1964 town hall, focused on race relations, in which she described how her father’s inability to secure full citizenship rights in spite of his legal wins led her to embrace more radical thinking about civil rights activism. (You can listen to her speech here.)

Speaking of her father, she said:

[H]e moved his family into a restricted area where no Negroes were supposed to live and then proceeded to fight the case in the courts all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. And this cost a great deal of money. It involved the assistance of NAACP attorneys and so on and this is the way of struggling that everyone says is the proper way to do and it eventually resulted in a decision against restrictive covenants which is very famous, Hansberry v. Lee. And that was very much applauded.

“But the problem,” she added, “is that Negroes are just as segregated in the city of Chicago now as they were then and my father died a disillusioned exile in another country."

This, she explained, is why she grew exhausted with white, liberal views on activism, which often suggested Black people take less aggressive stances in order to achieve the freedoms they sought.

“I wrote a letter to The New York Times recently which didn’t get printed,” she said at the start of her speech. And she pulled from that alleged letter in her later remarks:

I wrote to the Times and said, you know, ‘Can’t you understand that this is the perspective from which we are now speaking? It isn’t as if we got up today and said, you know, ‘what can we do to irritate America?’” It’s because since 1619, Negroes have tried every method of communication, of transformation of their situation: from petition to the vote, everything. We’ve tried it all. There isn’t anything that hasn’t been exhausted. Isn’t it rather remarkable that we can talk about a people who were publishing newspapers while they were still in slavery in 1827, you see? We’ve been doing everything, writing editorials, Mr. Wechsler, for a long time, you know.

The “Mr. Wechsler” Hansberry referenced was New York Post columnist James Wechsler, who had argued that Black activists associated with Hansberry were “ambushing captive white liberals” with their demands.

Hansberry said “the charge of impatience is simply unbearable,” and she issued a challenge of sorts for white people supposedly inclined toward freedom and justice for all.

“The problem is we have to find some way with these dialogues to show and to encourage the white liberal to stop being a liberal and become an American radical,” she said.

In a world where conservatives associate accountability with oppression, there’s no mystery why some of them have sought to keep Hansberry’s work away from America’s most malleable minds, She didn’t plead with white peers for freedom; she commanded it from them. And she used her brilliant words to shame them when they fell short.

Related: