When President Obama delivers the State of the Union Tuesday night, he will outline ideas that have been months in the making. The speech is typically the most watched presidential address of the year – 33 million viewers caught it live in 2014 – yet many people may not realize how much goes into the big night.

“This is sort of the World Series, and the Final Four, and the Super Bowl -- all rolled into one for the Obama speechwriting operation,” says Dan Pfeiffer, senior adviser to Obama.

On Friday, Pfeiffer offered a behind the scenes look into the process, from policy brainstorming with budget gurus to the president’s late night writing sessions in Hawaii.

BRAINSTORMING

“The fun part’s in the beginning, when you sit down with the president months before the speech, and let him just do a download of what he’s thinking,” Pfeiffer says, and those meetings provide “a map of where to go.”

Aides use that map to flesh out proposals.

“In September, you cull ideas from the cabinet agencies, from the policy councils here,” says White House Communications Director Jennifer Palmieiri. “Brian Deese, who’s deputy director at OMB, he manages that process,” Palmieri told MSNBC.

On the last Friday night before this year’s address, Deese was hard at work, chairing a State of the Union meeting of economists, White House aides and members of the National Economic Council. While many of the president’s junior press aides are crammed into tight quarters in the West Wing, Deese occupies a sprawling budget office in the Eisenhower building next door.

“We try -- to the greatest extent possible -- to wrap up the development process,” Deese explains, “before the really serious speechwriting begins.” Deese believes that is the best way to avoid “policy-making on the fly.”

Obama tends to use the draft speeches to audit ideas, Deese explains, asking questions like “can we afford that?” and “is that a high value investment of resources?”

“There are some issues that actually don’t have that big a price tag, but you still want to ask tough questions,” Deese says, adding that as an editor, Obama “pushes us to think rigorously.”

Then the president’s revisions start arriving.

As one of Obama’s longest-serving senior aides, Pfeiffer -- who has served in Obama’s inner circle since before he was president -- works out of a coveted office down the hallway from the Oval Office. But he still gets nervous about rewrites.

“There’s always like, sort of this moment of trepidation as you wait to get the president’s copy back, to see how far you are from actually getting it done,” Pfeiffer says.

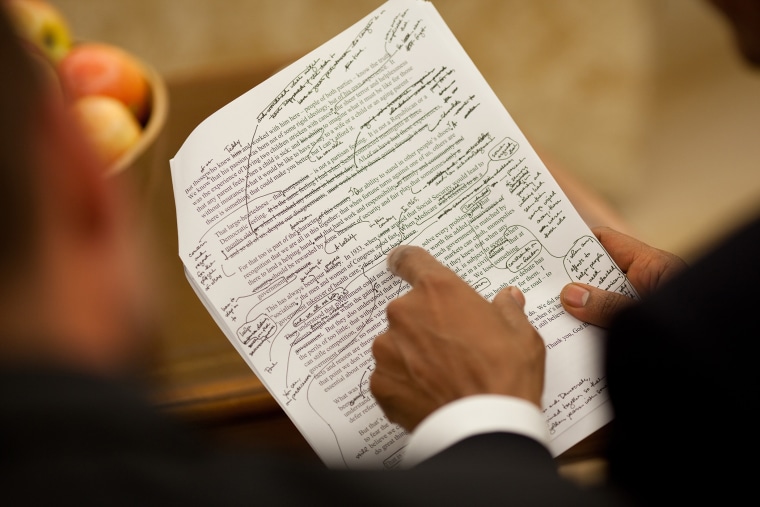

“We’ll either get email from him at night,” says Pfeiffer, or “long pages from a legal pad that he has written full grafs on -- sometimes pages with like arrows pointing to where it should go.”

As an author in his pre-presidential life, Obama clearly has his own style of writing and revising. And in an era of the personal computer, some aides marvel at his penmanship.

“He has extraordinarily neat handwriting -- it's surprising,” says Palmeri. “The first time I saw it, I thought it was a font,” she recalled.

CREDIT AND IDEAS

Historians note that presidents tend to use State of the Union addresses both to take credit for past achievements and roll out new plans. Second term addresses can focus more on taking credit, as a president aims to burnish a legacy and argue his policies are working. About 17% of Obama’s first term addresses focused on claiming credit, according to research by political scientists Alison Howard, and the president plans to herald a rebounding economy this year.

“What you’re going to see – both in the speech and his budget – is an explanation of what the president has done over the last six years,” says Deese, citing energy, health care and jobs programs, “[and] how they all fit together to build a firmer economic foundation.

The second term agenda, says Deese, is devoted to providing “middle class families more security, more opportunity and more of a sense that they fit in in the new economy.”

Reflecting on key lines in the address, Palmieri also cited the middle class. “There’s a phrase in the speech that I think really sums up the speech well,” she says, “It’s about the economy – it’s about the middle class.”

A TWO-SCREEN SPEECH

When all the rewrites are done and the president heads to Capitol Hill, the White House staff get to rest – sort of.

“When I worked for President Clinton, you could say, ‘Okay great, the speech is on, let’s sit and watch the speech and see an hour or so later what the reaction is,’” recalls Palmieiri. “Now we’re watching the speech in a very active way -- because of Twitter.”

White House aides usually gather in the press secretary’s office – “because it has a huge TV,” Pfeiffer explained – and watch the address with an eye on the web. “I’ll watch it on television with my phone in my hand,” Pfeiffer says, “and sort of track Twitter, and other social networks, [for] the two-screen experience to see what’s happening – which is how a lot of people are watching it these days.”

Related: How much do you know about State of the Union history?

Tracking Twitter discussion of last year’s address, Nielsen estimated that over eight million people saw tweets about it.

Obama’s aides are not just watching that conversation, of course, they’re trying to shape it.

On Friday evening, a young, diverse crowd of techies were still quietly typing away in the “Digital Strategy Office.” With three ornate rooms in the Eisenhower building, the area looks like a cross between a European embassy and a trendy start-up, with high ceilings and stone corbels giving way to goofy, photoshopped pictures of the president and marked-up white boards. For the State of the Union, the goal is to explain and enhance the speech online.

“Our theory is not everyone in America is going to want to hear a lot about a particular policy -- but we’re going to be able to reach the millions of people who really care about [certain priorities],” says Palmieri.

So the White House’s online broadcast of the speech includes a visual “river of content,” she says, with details on every topic the president raises. It’s an unapologetically wonkish approach; with 132 charts and graphics, last year’s version was the mother of all PowerPoints. And apparently, the wonks are out there: Last year’s address drew 1.4 million views.

Despite all the changes surrounding this historic address, that’s one thing that hasn’t changed – given the option, many Americans do want to hear directly from the president about how things are going – about the state of our union.