For many pundits watching the lack of progress on sequestration cuts, there was a reflexive instinct to blame President Obama. If he'd get congressional Republicans to do what he wants them to do, the president would demonstrate "leadership." It's a sad argument that overlooks separation of powers, Civics 101, and the basic structure of party politics, but we've heard it quite a bit anyway.

On Friday, however, after Obama said he's tried everything he can to reach a fair compromise with congressional Republicans, National Journal's Ron Fournier marveled that the president "can handle bin Laden," but not House Speaker John Boehner.

In fairness, it's sometimes hard to tell when Fournier is kidding, and I honestly have no idea if a comment like this was made in jest. But I don't think so -- Fournier has been one of the more assertive pundits insisting in recent weeks that Republican intransigence must somehow be Obama's fault. It stands to reason that the National Journal writer genuinely doesn't know how and why the president can take charge on national security, but struggle with Congress.

Indeed, if I had to guess, I'd say low-information voters nationwide may have the same question. If Obama has "worked his will" on national security, ending the war in Iraq, decimating al Qaeda, launching the bin Laden mission, helping take down the Gadhafi regime, etc., why does the president have so much trouble reaching simple fiscal compromises with lawmakers?

The answer has a lot to do with where presidents have broad power -- and where they don't.

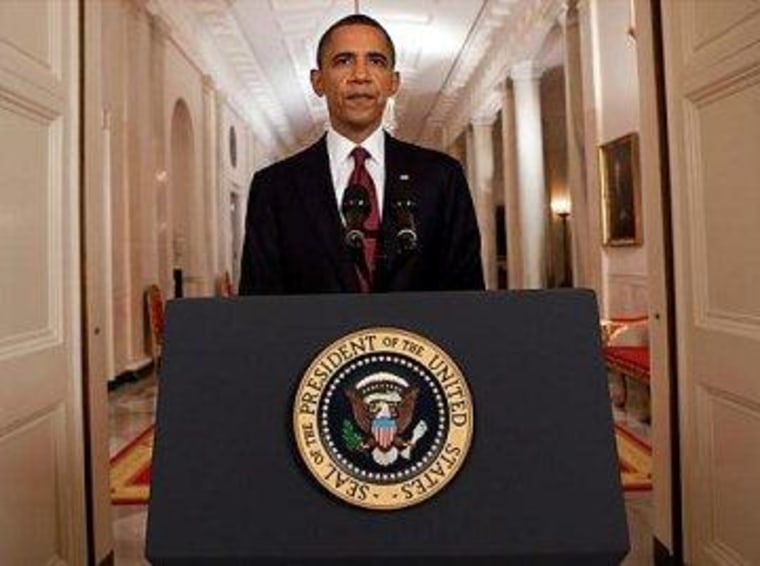

To Fournier's question, Obama didn't exactly "handle" Osama bin Laden, so much as ordered the strike that killed Osama bin Laden. The president, in his capacity as Commander in Chief, reviewed the intelligence, weighed his options, consulted with his team, and made a decision. That decision was then carried out, exactly as the president had instructed.

And why can't Obama demonstrate similar leadership qualities when dealing with Congress? Well, probably because it's wise not to think of the duly-elected Speaker of the House as a dangerous adversary, but rather, as a constitutional officer who helps lead a co-equal branch of the American government.

When it comes to national security and foreign policy, a president has ample opportunities to "take charge." It's baked into the cake -- he or she has unique responsibilities and powers. We can and should debate the appropriate limits on those powers, and how best they should be subjected to checks and balances, but for the modern presidency, the scope of authority over the use of force is quite broad.

When President Obama, for example, decided to give the green light to the mission in Abbottabad, Republicans were given no filibuster opportunities; there was no consideration of the "Hastert Rule" in the House; and there were no pleas for votes or need for legislative arm-twisting.

For good or ill, the process is incredibly efficient -- the administration presents a chief executive with information; the chief executive makes a decision; that decision is executed. Period. Full stop.

The legislative process, whether pundits like it or not, includes infinitely more choke points at which progress can come to an immediate stop. The executive branch can no sooner tell the legislative branch what to do than vice versa -- the president is not Congress' boss and the Speaker can ignore a president's wishes for any reason.

And here's the kicker: this is a feature, not a bug. We don't want an American system of government in which a president can "handle" a Congress the way he or she "handles" a terrorist threat. Checks and balances, warts notwithstanding, are to be celebrated, not denigrated.

Does this mean a president will have greater opportunities for unilateral success on foreign policy? Yes. Should we hope a president has similar authority to give orders to Congress? Absolutely not.