As President Joe Biden got to work on his first full day in the White House, there was a common thread tying together each of the day's major political headlines. It was far from subtle.

Are Republicans prepared to consider the White House's new economic relief package? No.

Senate Republicans vowed Thursday that President Joe Biden's coronavirus relief bill will not get 60 votes, daring the White House to either compromise with the GOP or use partisan procedural tactics to evade their filibuster.

Are Republicans prepared to consider the White House's new immigration reform proposal? No.

President Joe Biden's sweeping immigration plan ran into quick resistance from key Senate Republicans, including some who championed a similar effort eight years ago.

Are Republicans prepared to consider accountability for Donald Trump following his role in inciting a deadly insurrectionist attack on the Capitol? No.

Senate Republicans are coalescing around a long-shot bid to dismiss the impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump before it even begins, relying on a disputed legal argument that says putting an ex-president on trial is unconstitutional.

Are Republicans prepared to accept the new president's authority to pursue priorities through executive actions? No.

Joe Biden has been president for a little more than 24 hours, and Republicans are alleging that he has already poisoned the well when it comes to getting Congress to act on his agenda. Biden signed 17 executive actions after being sworn in Wednesday, and conservatives say this amounts to an end-run on Congress actually legislating.

Are Republicans prepared to allow the Senate to organize under the new Democratic majority? No.

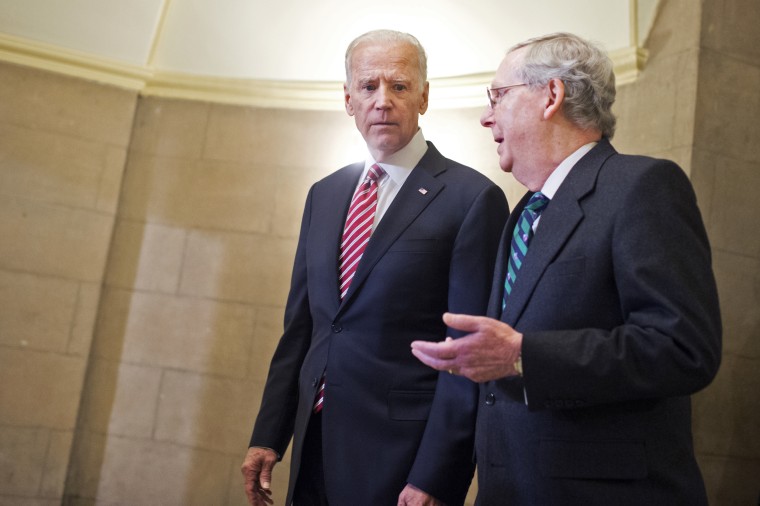

Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, now in the minority, is insisting language assuring the protection of minority rights -- through the requirement that 60 votes are needed to overcome filibusters of bills -- be added to a must-pass organizing resolution.

The circumstances are frustrating for those eager to see effective governing, but they shouldn't surprise anyone. GOP leaders wrote a playbook the last time Democrats controlled the White House and both houses of Congress, and they're obviously running the same plays again.

As we recently discussed, observers need only look at Mitch McConnell's actions in early 2009 to get a sense of how the Kentucky Republican approaches his governing responsibilities when Democrats control the levers of federal power.

As I noted in my book, after President Barack Obama was inaugurated in 2009, Republicans were under some pressure to be responsible and constructive, with many pleading with GOP officials to resist the urge to slap away the Democratic president's outstretched hand. McConnell executed a different kind of plan, refusing to even consider bipartisan governing, even when Obama agreed with his opponents.

As the Kentuckian saw it, the public believes bipartisan bills are popular, so he rejected every element of the Democratic White House's agenda so voters would not see Obama succeeding. "We worked very hard to keep our fingerprints off of these proposals," McConnell told The Atlantic in 2011, referring to legislation backed by the White House.

McConnell was surprisingly candid on this point. "Public opinion can change, but it is affected by what elected officials do," the GOP leader told National Journal in March 2010. "Our reaction to what [Democrats] were doing had a lot to do with how the public felt about it. Republican unity in the House and Senate has been the major contributing factor to shifting American public opinion."

In other words, McConnell felt like he'd cracked a code: Republicans would make popular measures less popular by killing them. McConnell's plan was predicated on the idea that if he could just turn every debate into a partisan food fight, voters would be repulsed; Obama's outreach to Republicans would be perceived as a failure; progressive ideas would fail; and GOP candidates would be rewarded for their obstinance.

McConnell added soon after, in reference to his party's approach to policymaking, "The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.... Our single biggest political goal is to give our nominee for president the maximum opportunity to be successful."

This is the senator's vision. It is not a secret. With Biden in the Oval Office, McConnell has a guiding principle: Failure is the goal. His priority is to position his party to retake the Senate majority after the 2022 midterms, and then elect a Republican president in 2024. Working constructively with a Democratic White House would do little to advance these objectives, which is precisely why he will choose a maximalist partisan course: because gridlock and dysfunction will give McConnell more of what he wants.

Yesterday was the first day in which the GOP reembraced its Party of No label. It won't be the last.