In the opening scenes of season 18 of “The Bachelorette,” we meet our new lead: 28-year-old teacher Michelle Young. We see “Miss Young” teaching adorable fifth graders fractions. We see her talking to her extremely Minnesotan (and extremely in love) parents about their perfect marriage. We watch her twirl and “woo!” on a random bridge, do a photo shoot in one gown and then change into another gown to shoot basketballs into crystal-encrusted hoops. We watch her “woo!” again in a red convertible, perfectly wavy hair blowing in the wind as she drives through Indian Wells, California, with the top down.

It’s glamorous. It’s sweet. It’s over the top. It’s corny as hell. And as I watched this sequence play out, I let out a sigh of relief.

Maybe, just maybe, “The Bachelorette,” one of the most aggressively white, conservative shows on television, is going to let Young, a biracial Black woman, be more than a token or an empty symbol. Maybe Young is going to be allowed to just search for true love.

Anyone who has dedicated precious time over the years to watching “The Bachelor,” “The Bachelorette” and “Bachelor in Paradise” (RIP, “Bachelor Pad”), knows that it’s unwise to expect much from the franchise in the way of social progress. This is especially true when it comes to race.

It took 15 years — and a 2012 class-action suit — for the franchise to cast its first Black lead, making attorney Rachel Lindsay the titular Bachelorette in 2017. But with no Black producers working with her and no Black executive producers working on the show at the time, the season was a disappointment. (Young’s season is the first with a Black executive producer, Jodi Baskerville.) Lindsay, by her own account, had to be “a good Black girl, an exceptional Black girl,” to try to be accepted by the Bachelor’s overwhelmingly white audience. And she was left to navigate the weight of being The First in a white, at times overtly racist, space alone.

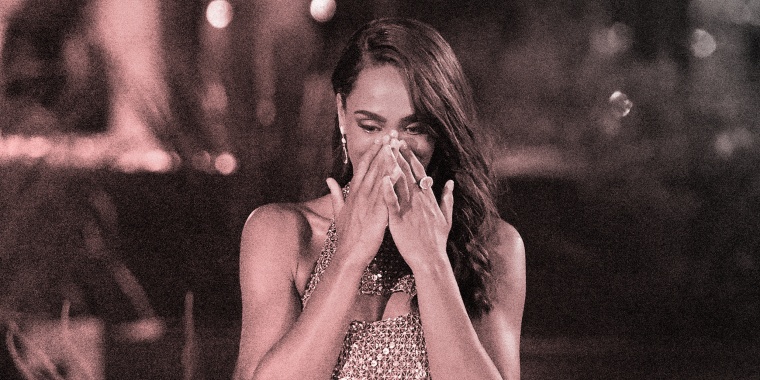

At one point during filming, Lindsay broke down, explicitly telling production: “You are leaning on me to guide you through what it’s like to handle a Black lead. And I have to be the Black lead. I have to educate y’all and navigate my system.”

Lindsay did find love on the show, although she has expressed frustration with the show’s choice to focus more on her runner-up.

Ultimately, Lindsay did find love on the show, although she has expressed frustration with the show’s choice to focus more on her runner-up, a white man, than her now-husband, Bryan Abasolo, who is Latinx. Her relationship didn’t receive the fairytale treatment many fans had hoped for. Three years later, in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd and national reckonings about institutional racism, the franchise scrambled to cast a Black man, Matt James, as “The Bachelor.” But yet again, they failed to stick the landing, and the season ended in a storm of racial controversy. Longtime host Chris Harrison was ousted (with a reported $9 million payout) for going on a tone-deaf, racist tirade during an interview with Lindsay, and James publicly stated that “The Bachelor franchise has fallen short” when it came to its handling of race and racism.

But, wait! Perhaps now was the moment when “The Bachelor” would choose someone other than a middle-age, square-jawed white man to be the steady hand that leads audiences through each season. Emmanuel Acho filled in for Harrison during an “After the Final Rose” special, and former Bachelorettes Tayshia Adams and Kaitlyn Bristowe co-hosted the following season of “The Bachelorette” (and they’ve returned to host the current one). For a second, it seemed like the franchise maybe wasn’t so invested in centering white men as the voices of authority on a show primarily geared at women.

But then news broke that Jesse Palmer, a 43-year-old, square-jawed white man, would be “The Bachelor's" new, permanent host. Because as the adage goes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

The safest thing is always to expect the least from “The Bachelor.” After all, it’s a reality show, one that is intensely invested in the fetishization of heterosexual marriage. But many fans — especially those who recognize the place the 20-year-old franchise occupies in the cultural square — keep letting themselves ask for more, for better, for greater humanity from this silly show. And those fans, myself included, are still holding out hope that “The Bachelorette” will do better by Young.

There is a reason that the broader “Bachelor” franchise has managed to stay appointment television, even as the primacy of networks fade in the era of unlimited binge-watching. Its appeal is tied to the near-universal desire to find love, and the fantasy that doing so just requires “opening up” and “being vulnerable” over the course of eight weeks to a set number of potential romantic partners. The simplicity is why it works.

There is a reason that the broader “Bachelor” franchise has managed to stay appointment television, even as the primacy of networks fade.

“The Bachelor” and “The Bachelorette” are fundamentally a portal into romantic fantasy; products with the same basic appeal as “Pride and Prejudice,” “When Harry Met Sally” and Netflix’s “Bridgerton.” It’s the marriage plot in a reality TV package. And it's deeply satisfying to watch.

“We are not as cynical as we pretend to be,” Roxane Gay wrote in 2014 about feminist fans of “The Bachelor.” “The real shame of ‘The Bachelor’ and ‘The Bachelorette,’ of the absurd theater of romantic comedies, of the sweeping passion of romance novels, is that they know where we are most tender, and they aim right for that place.”

We don’t want cynicism to be our dominant emotion when watching Young’s journey. We want all of the absurd theater, and we want to watch Young be herself during — or is it despite? — the drama. We want to watch Young go on fantastical dates, and dump men who aren’t right for her. We want to watch her be desired. We want to watch her be loved. We want to be fully absorbed by the ridiculous, overwrought, deeply satisfying performance of it all.

“I went on the show in part because I wanted to depict a Black woman at the center of a love story,” wrote Lindsay in that same June essay. “However, it’s up to the producers to display your happy ending.”

We want to watch Michelle Young get her happy ending, no matter how constructed it ultimately is. What a beautiful and absurd journey this could be.