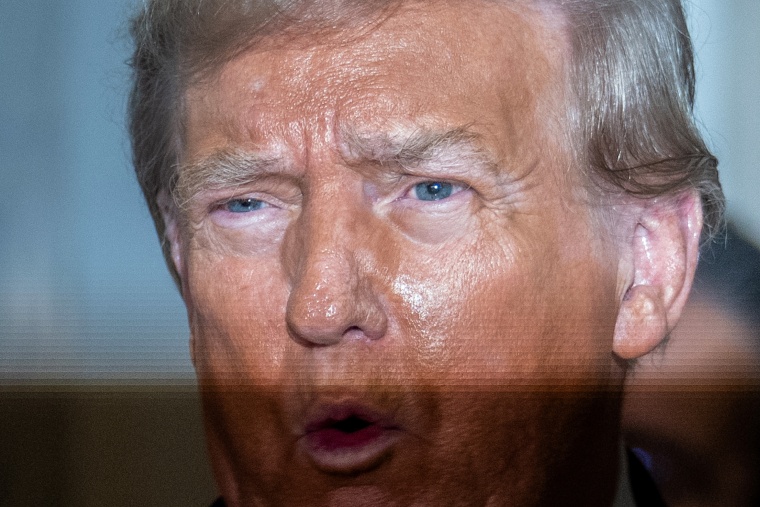

Former President Donald Trump has offered up some questionable arguments to try to squirm out of legal trouble before. But his latest argument may be the boldest yet. Trump is claiming that it’s unconstitutional to proceed with the federal case charging him with trying to overturn the 2020 presidential election and subvert lawful votes because he was acquitted for those same activities in his second impeachment trial.

In an amazing bit of spin, Trump’s team treats the word “convicted” as his get-out-of-jail-free card.

That argument was included in one of three motions to dismiss that Trump’s lawyers filed Monday night. Claiming, as Trump’s team does, that “the impeachment and double jeopardy clauses both bar retrial before this Court and require dismissal” requires a willful misunderstanding of the impeachment process.

Trump’s lawyers focus on Article I, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution, which deals with the possible sentences for impeachment convictions, specifically the part that reads, “the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.” You might read that and think that it’s bad for Trump, as it clearly implies that an official who’s been impeached can be criminally charged. But, in an amazing bit of spin, Trump’s team treats the word “convicted” as his get-out-of-jail-free card. According to Trump’s motion: “As the Senate acquitted President Trump, the prosecution may not re-try him in this Court.”

That’s incredibly wrong for several reasons. First, there is a very clear distinction between impeachment trials, which are political, and criminal trials, which ought not to be. There is no standard in a Senate impeachment trial that comes close to the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard in a criminal case. Nor is there any need for unanimity among the jury as in federal criminal cases, as only two-thirds of senators are required to vote in favor of conviction — which thanks to partisanship can be an even higher bar.

According to the Constitution, the required punishment for an official convicted in an impeachment trial is removal from office. The other, optional sentence is to be barred from holding any future office, a punishment that would have blocked Trump from his current presidential run. In the federal criminal case charging him with trying to overturn the 2020 election, Trump is charged twice with a crime that carries a maximum prison sentence of 20 years, once with a crime that has a maximum 10-year sentence and once with a crime that has a maximum five-year sentence.

The idea that the Senate’s trial of Trump — where acquittal was a foregone political conclusion, divorced from the facts that a criminal trial requires — put him “in jeopardy of life or limb” makes no sense. He was in danger of, at most, not being able to hold office again, not any sort of jail time or monetary fine. And even then, Senate Republicans claimed (incorrectly, in my view) that because Trump had left office by the time of his second impeachment trial, he couldn’t be convicted in the upper chamber but that the regular courts would be able to sort things out. As Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said in his speech after voting to acquit, “We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.”

In his “Commentaries on the Constitution,” Justice Joseph Story, one of the first scholars of the Constitution and an expert McConnell cited in his speech, did write that even after leaving office, former officials were “still liable to be tried and punished in the ordinary tribunals of justice.” He also wrote what is a clear rebuttal to the argument about “double jeopardy” that Trump’s lawyers put forth on Monday night:

If the court of impeachments is merely to pronounce a sentence of removal from office and the other disabilities; then it is indispensable, that provision should be made, that the common tribunals of justice should be at liberty to entertain jurisdiction of the offence, for the purpose of inflicting, the common punishment applicable to unofficial offenders. Otherwise, it might be matter of extreme doubt, whether, consistently with the great maxim above mentioned, established for the security of the life and limbs and liberty of the citizen, a second trial for the same offence could be had, either after an acquittal, or a conviction in the court of impeachments. And if no such second trial could be had, then the grossest official offenders might escape without any substantial punishment, even for crimes, which would subject their fellow citizens to capital punishment.

Justice Joseph Story

Translation: These are two very different courts exercising very different powers. It makes zero sense that an acquittal in an impeachment court, with its limited scope, should prevent a criminal court from trying the same person for those actions under the full scope of the law. Otherwise, someone like, for example, a former president, could walk away scot-free because an impeachment court didn’t use its limited powers to punish a crime that would normally draw much more severe penalties.

Let’s not forget that a federal judge already dismissed Trump’s claim in a civil lawsuit that the Senate’s acquittal triggered the “double jeopardy” clause. “President Trump offers no evidence to support a conclusion that the Framers intended for the absence of any reference to an acquitted officer following impeachment to mean that such official could not be subject to judicial process,” Judge Amit Mehta wrote in February 2022.

As far as long shots go, this latest one is a doozy. There’s an air of desperation in trying a play that has already failed, especially one that has failed so spectacularly. It may be that Trump is, as ever, just trying to buy more time and drag out the proceedings. But you’d think that he’d at least try to find an argument that doesn’t immediately make you wonder if his lawyers are even trying.