UPDATE (Feb. 8, 2024 11:04 p.m. E.T.): On Thursday night, NBC News projects that Donald Trump is the winner of the Nevada Republican caucus. Trump’s main rival Nikki Haley was not on the caucus ballot.

On Tuesday, Nevada held its GOP presidential primary. On Thursday, the state Republican party holds presidential caucuses — with an entirely different ballot. The path to this strange setup started in 2021, when the Democratic-controlled state Legislature enacted a law requiring a “presidential preference primary.” But Nevada Republican officials preferred a type of contest they believed would help former President Donald Trump, whose passionate supporters can be counted on to turn out. So the state party announced that it would hold caucuses a few days after the state-mandated primary, and they would be the only way candidates could win delegates. But candidates can compete in only one of these dueling contests — which means former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley, by being on the primary ballot, won no delegates.

The Nevada GOP’s move may seem radical, but it’s less rare than you might imagine. In December, after Colorado’s Supreme Court struck Trump from the Republican primary ballot, the state’s Republican Party responded by proposing that it abandon the primary altogether and hold caucuses, instead. Quite a few state parties regularly shift back and forth between caucuses and primaries for picking presidential nominees. And they do it for several reasons but one overarching purpose: to exert control and achieve party goals.

It’s key to understand the distinction between primaries and caucuses. A primary is a simple election. People can vote in it quickly and, in many states, from home. Caucuses, often run by the state parties, require more time, usually several hours on a weeknight, and they can be far more social and even confrontational. As a result, caucus turnout is usually much lower and limited to the most committed party members and candidate supporters. The decision about which to hold can thus affect what sorts of people participate and which candidate ends up winning.

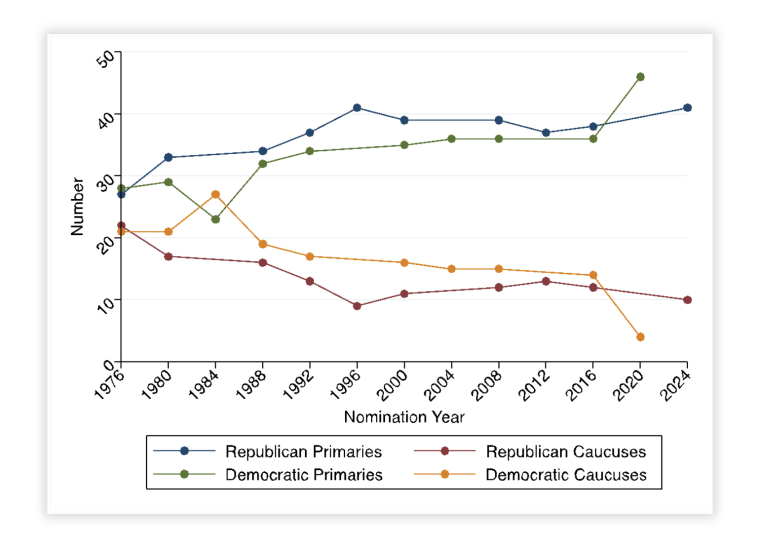

Caucuses have gotten a bad rap in recent years, and Democrats have been phasing them out. The Iowa Democratic caucuses, in particular, came under fire in 2020, both because of logistical snafus that delayed the reporting of the results and because its low-turnout nature in a very white and rural state made it especially unrepresentative of the party’s national makeup. Republicans, however, have been less concerned with low turnout and have had less reason to worry that caucuses are unrepresentative. Roughly a dozen state GOPs have held caucuses for the past three decades, as the chart below shows.

Though the figure looks fairly stable, with small shifts over time, in any given election cycle, three or four state parties change from caucuses to primaries and two or three make the opposite switch. But just what is it that makes a party switch its contest type? In examining contemporaneous local media and scholarly accounts of the switches, we found a number of reasons.

In some instances, the changes were simply to comply with party rules. Last year, Michigan’s Democratic-controlled Legislature, working with the Democratic National Committee, moved its 2024 primary to February. However, current Republican National Committee rules prevent most states from holding their contests before March 1. So the state’s Republicans are holding party-run caucuses on March 2.

In other instances, logistical issues prompted format changes. Caucuses tend to break down when there are too many people or not enough. Several states, including Colorado, Idaho and Minnesota, abandoned their Democratic caucuses after 2016 because of complaints from caucusgoers about the crowds and disorganization. But since states administer primary elections, when budgets are lean, they’ll occasionally try to put the parties in charge of picking candidates through caucuses.

Sometimes a state party has a very negative experience with a contest and makes sharp rules changes to avoid a repeat. In 1988, for example, Jesse Jackson accused Colorado Democrats of slow-rolling their March caucus tallies so they wouldn’t influence Wisconsin’s primary, held the next day. The state party, stung by the accusations, switched to a primary in 1992 to avoid a repeat of that scandal.

Finally, some states change their contest type to try to increase their influence in the nominating process. In 1988, Kentucky, Oklahoma and Virginia all switched from caucuses to primaries to join forces with other Southern states for Super Tuesday, hoping grouping their contests would draw candidate and media attention to the region and help moderate Democrats.

And as we are seeing in Nevada this week, in some cases, state parties will even put their thumbs on the scale for or against specific candidates. In 1996, Sen. John McCain pushed the Arizona Legislature to switch from caucuses to a primary in the hope that it would advantage his preferred presidential candidate that year, Sen. Phil Gramm of Texas. That switch to a primary helped McCain in his own campaign in 2000. In 2016, Sen. Rand Paul pushed the Kentucky Republican Party to adopt caucuses so he could run for president while still being a candidate in the state’s Senate primary. Paul even paid for the caucuses himself!

Looking back, it’s unclear just how often this kind of power has actually determined the nominee. Had more state Democratic parties opted for primaries instead of caucuses in 2008, it’s plausible that Hillary Clinton, not Barack Obama, would have become the nation’s 44th president. It’s plausible that, had Trump struggled more this year, the decision by some state parties, like Nevada’s, to opt for caucuses could have aided his nomination.

But regardless of the reason for changing format or the impact of specific changes in specific years, the important lesson is just how active state parties are in choosing and shaping contests. The familiar narrative of the past half-century of party nominations is that the voters are in charge and that parties have little, if any, power to steer the contests. But Nevada’s caucus/primary week shows us that parties aren’t passive. While voters may choose, the parties dictate how we choose and whom we get to choose from.