Last year, when I saw Hasan Minhaj perform stand-up comedy in New York, he told a joke about how he came across a drunk white woman who was vomiting on the side of the street, and when he went to check if she was alright, she looked up and asked if he was her Uber driver. I rolled my eyes, turned to my friend and called bulls---.

Turns out it probably was.

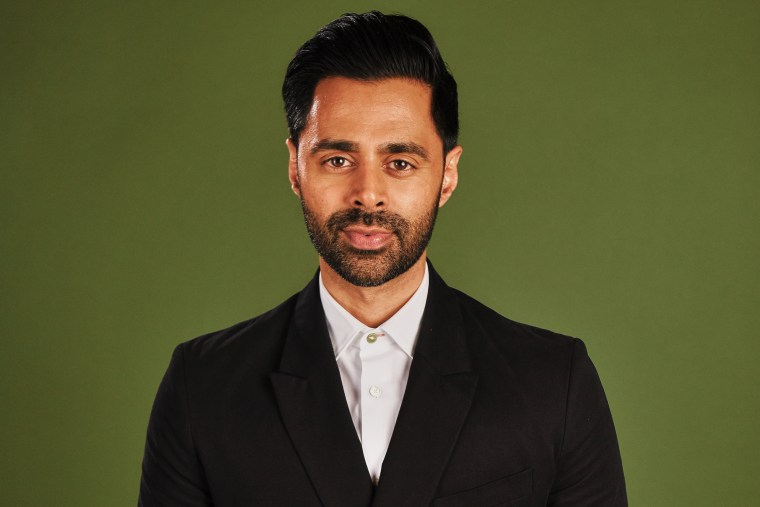

The comedian, a Muslim Indian-American, who has built a brand and career around autobiographical comedy with political overtones — often centering himself in stories where he is subjected to racism — turns out to have been lying. A New Yorker exposé, written by Clare Malone, found that his stories are often either wild embellishments or just never happened. He is the boy who cried racist wolf. And although Minhaj staunchly defended his lies and embellishments to Malone, claiming they reflect “emotional truths” that need to be addressed, he is instead hurting people of color — not helping them.

Lying about racism does a huge disservice to racial and ethnic minorities, and it will likely only buttress white supremacy, an apparatus designed to belittle and deny racism as it is. Having a high-profile brown person build his career in part around fabricated experiences with racism will only feed into this narrative.

Lying about racism does a huge disservice to racial and ethnic minorities.

In “The King’s Jester,” a 2022 Netflix comedy special, Minhaj tells the harrowing story of how he received through the mail some white powder, which he and his wife suspected was anthrax and which spilled all over his toddler daughter when Minhaj opened it. They rushed her to the hospital. It is just one example, he claims, of the targeted harassment he experiences as a result of his politics and work.

But after Malone interviewed Minhaj’s doormen, his residence’s mailroom employees, security personnel hired through his show and his personal security guard — and after reviewing records from local hospitals and the New York Police Department team that’s tasked with investigating anthrax — Malone could find no evidence of the incident. When she challenged Minhaj on this, he admitted it never actually happened but did claim that someone had once sent him white powder (which, interestingly, he never informed anyone on his security team of).

In his other Netflix stand-up special, “Homecoming King,” Minhaj tells the heartbreaking story of how the white girl who had agreed to go to prom with him ultimately rejected him and went with a white boy instead — something Minhaj only learned about when he arrived at her house, all dressed up and ready to take her to the dance, and the other boy was already there. Her family didn’t want her prom pictures to be with a South Asian boy, they said. In a sick twist of irony, he alleges, she went on to marry an Indian man.

However, according to this woman, they were good friends at the time and the rejection never happened (she declined his invite before the prom), which Minhaj confirmed when confronted by Malone. Yet, disturbingly, he invited the woman and her husband to the Off-Broadway version of the show and did little to conceal their identities (projecting real pictures of them on stage, blurring out only the faces). What ensued for this woman was years of harassment and doxing, which Minhaj dismissed when she approached him about it.

Then there’s the FBI informant, a white man named Craig Monteilh, who pretended to be Muslim and supposedly infiltrated Minhaj’s mosque when Minhaj was a teenager in 2002 — another compelling and outraging story from “The King’s Jester.” As Minhaj’s story goes, his family hosted Monteilh at their house for dinner, and some time afterward, a suspicious young Minhaj decided to test the waters by telling Monteilh he planned to learn how to fly an airplane. Shortly after, the police violently apprehended Minhaj.

As Malone explains, Minhaj supports this story in his show with news footage of Monteilh. Never mind the fact that in 2002 Monteilh was actually in prison and that he didn’t become an informant until 2006. Or that since leaving the FBI, Monteilh has lambasted the institution for its informant program and argued that the FBI should apologize to the Muslim communities. “Minhaj said that he owed nothing to Monteilh, based on his behavior toward the Muslim community,” Malone writes. Minhaj is self-righteously playing god when it comes to any fallout Monteilh might experience as a result of this high-profile fabrication.

These lies and embellishments — and Minhaj’s justifications for them — are equal parts disturbing and hubristic. In a world that constantly denies and minimizes the daily hostilities and indignities of being a minority, in a system that often leads white people to accuse people of color of exaggerating the racial reality, Minhaj’s lies could vindicate denialists and embolden white supremacy.

A 2019 study in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science, which looked at attitudes toward racism amongst white and Black university students and how different history curricula inform these attitudes, found that (unsurprisingly) white students had a “greater denial of systemic racism.” Phillipe Copeland, clinical assistant professor at Boston University’s School of Social Work, explored this phenomenon of racism denialism in a Boston Globe op-ed in January titled, “The art of the denial: How racism deniers obscure the reality of racism, minimizing its significance.”

“Racism denial is a political strategy,” he writes. “Its proponents know they benefit from racism and want to perpetuate it. They attempt to convince people racism is no longer an issue or is not a big enough one to require attention.”

Copeland added that it is also a coping mechanism for “the contradiction of living in a society that preaches equality, freedom, and democracy but often practices the opposite."

In lying about his experiences of racism, Minhaj is, at best, supporting a deeply pernicious collective coping mechanism. At worst, he is emboldening the political strategy of the right — either of which makes it harder for people of color to be believed and humanized.

In lying about his experiences of racism, Minhaj is, at best, supporting a deeply pernicious collective coping mechanism.

What’s more, Minhaj has branded himself as a thoughtful, intellectually probing political commentator (this was the premise of his comedy news show, “The Patriot Act”), who purportedly offers nuance to stories and themes of social justice. But his lies and embellishments completely disregard intersectionality, instead painting a reductive picture of racism in which white people are always the aggressors and people of color like Minhaj are always the victims.

I am Pakistani American, I am culturally Muslim, and I have experienced racism in all shapes, colors and sizes. But it would also be intellectually dishonest and disingenuous to omit the context of my privilege. I am also half-white and have been afforded the benefit of a world-class education; I have cultural capital and financial security — I am, in many ways, more privileged than most white people in this world. Minhaj, however, makes no mention of his privilege.

In fact, he uses his privilege to target people with less power and influence than he has, sometimes ruining their lives (as was the case with his erstwhile prom date). In every story, he is the brown David to a white Goliath. But in lying and painting himself as the fictional victim, he both weaponizes racism and becomes an oppressor, the very same kind of role he critiques in his work.

This is also a role he and other members of his team fulfill behind the scenes. The New Yorker profile mentions three women who worked at “The Patriot Act” and initiated legal proceedings “alleging gender discrimination, sex-based harassment, and retaliation.” That matter was ultimately settled out of court. And when two researchers, women tasked with fact-checking, challenged some of Minhaj’s material in the writers’ room, they were told to leave and waited in the hall for the remainder of the meeting. They were disinvited to future such meetings, to which only their male boss was invited. (The co-creator of the “Patriot Act” said that this was to “streamline the show’s process,” and Minhaj defended the show’s fact-checking as “extremely rigorous.”)

These allegations, while shocking and disappointing, are also not surprising. South Asian masculinity breeds its own special brand of misogynistic toxicity. Yes, being a person of color can mean being subjected to a lifetime of racism — we cannot escape white supremacy — but it doesn’t mean you can’t also be Goliath.

Minhaj’s fictional victimization undermines the social justice sensibilities he purportedly supports. His defense — that his work advances important “emotional truths” — is intellectually dishonest and alienates some white people who might otherwise be sympathetic. Plenty of brown and Black people have genuinely experienced the kind of painful stories he’s concocted. Tell their stories.

Instead, Minhaj, using his own privilege, has co-opted their pain to advance his career, thereby making it harder for people with less privilege to be believed in the process.