This post has been updated.

Republican David Jolly owes his victory in last week’s special election for a Florida House seat to a flood of outside spending by conservative groups, most of it fueling a barrage of negative attacks against Democrat Alex Sink.

Many of the biggest-spending organizations in support of Jolly had familiar names. But one that played a key role in the win has largely flown under the media radar: the American Action Network (AAN).

As Republicans aim to win control of both houses of Congress this year, AAN, led by a team of GOP heavy-hitters, is emerging as a powerful player alongside better-known outfits funded by the billionaire Koch brothers and GOP strategist Karl Rove. And it’s one of the most effective at exploiting weak campaign finance rules to keep the source of its funding secret while working to influence elections.

AAN might not be a household name. But if Republicans are left in total control of Congress after this fall, the group could end up being a key reason why.

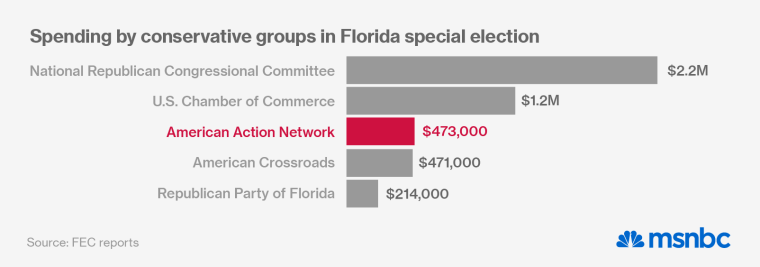

In Florida, AAN spent $473,000 attacking Sink. Among outside groups backing Jolly, only the National Republican Campaign Committee (NRCC)—the House GOP’s campaign arm—and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a perennial powerhouse, spent more.

Other conservative groups generated headlines by attacking Sink over her support for Obamacare. Meanwhile, AAN ploughed a lone furrow with ads that blasted Sink’s record as Florida’s CFO, charging that during her tenure, Florida’s pension funds lost billions because of mismanaged investments. With seniors a key demographic in the district, the attack shrewdly played on fears about retirement security.

AAN’s leadership gives it the cachet and connections to rake in contributions even in the crowded field of conservative groups looking to sway elections. It was launched in 2010 by Fred Malek, a veteran Republican money-man who served as co-finance chair for Sen. John McCain's 2008 presidential bid. (Malek may be best known as the White House aide who dutifully led an effort, instigated by President Richard Nixon, to count the number of Jews at the Bureau of Labor Statistics). AAN is chaired by Norm Coleman, the former Minnesota senator, and ex-GOP-congressmen Vin Weber, Jim Nussle, and Tom Reynolds sit on the board. AAN's president, Brian Walsh, is a former political director of the NRCC.

Even as it was helping to bankroll the anti-Sink effort, the group was looking ahead to the fall.

Earlier this month, AAN announced a $1 million campaign going after nine Senate Democrats over Obamacare’s cuts to Medicare Advantage, which is part of the law's goal of cutting health-care costs. Among the campaign’s targets are Senators Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, Mark Pryor of Arkansas, and Kay Hagan of North Carolina—the three most vulnerable Senate Democrats this cycle, as well as six vulnerable House Dems.

Of course, the Medicare Advantage attack is deeply misleading—the GOP voted overwhelmingly for those same cuts when they were part of Rep. Paul Ryan’s budget proposal the last three years. But when it comes to political attack ads, when has that mattered?

AAN also gave $1.5 million last year to the American Action Forum, a sister organization that describes itself as a "21st Century center-right policy institute."

AAN didn’t come out of nowhere this year. In 2011-12, it spent over $10 million attacking Democratic candidates. But in that cycle, Karl Rove’s American Crossroads Super PAC—which as of 2010 reportedly shared an office with AAN—set itself up as a clearinghouse for conservative money, and became the public face of the right’s outside spending, so smaller groups like AAN didn’t get much attention. This time around, for a host of reasons, things are splintering—making AAN and similar groups into more important players.

And unlike American Crossroads, AAN has been able to keep the sources of its funding secret, even while playing a growing role in electing Republicans. AAN is a 501(c)4 non-profit, meaning that under current IRS rules, it’s not required to disclose its donors or pay taxes, as long as it pledges that direct election work will be less than 50% of its activities. Many campaign finance experts say the 50% threshold allows groups whose primary purpose is political, not philanthropic, to unfairly claim tax-exempt status and keep their donors secret—an issue that flared last year after Republicans claimed the IRS had wrongly targeted conservative groups for scrutiny of their tax-exempt status.

Indeed, AAN is a leading practitioner of that strategy. The Center for Responsive Politics, a leading campaign finance watchdog, recently created rankings that combine a group’s direct political spending with the percentage of its spending that goes to political activities, to gauge which groups have been most effective at pushing the limits of the IRS’s rules. AAN ranked second, behind only Rove’s Crossroads GPS, the dark money 501(c)4 arm of American Crossroads.

Malek, the group's founder, told msnbc that for this fall, AAN expects to focus far more on the House than the Senate. "We have not yet narrowed down to where the most competitive House races will be, but the vast majority of our activity will be House races," Malek said.

Mostly, though, the group is pragmatic. "We’re not so much ideoliogically driven as we are issues driven," Malek said. "We want to support issues that are important to us and we want to support candidates who can win."