“The idea that so many children are born into poverty in the wealthiest nation on Earth is heartbreaking enough,” President Obama said recently in a speech on inequality. “But the idea that a child may never be able to escape that poverty . . . should compel us to action.”

The president was talking about economic mobility, but a deep and growing inequality is also the defining feature of the nation’s health. As a new report from the United Health Foundation makes clear, the United States is effectively two countries—one a model of robust health and increasing longevity, the other a land of diminishing prospects. Health care reform may help us bridge the two Americas, but the problem goes far beyond access to medical care.

The new report, an annual health ranking of all 50 states, uses measures ranging from smoking and obesity to child poverty to show how each state is faring in relation to the others, and how the United States is doing in relation to other developed countries. The news is not all bad.

Over the past year, the nation’s health has improved on 20 of the 28 indicators the report tracks. The smoking rate continued its decades-long decline. The proportion of adults getting no physical exercise fell by 12% (from 26% to 23%). And for the first time since 1998, the national obesity rate plateaued (at 28%) instead of rising. Infant mortality has fallen by nearly 40% since 1990, and fewer adults are dying before age 75, thanks to declines in heart disease, violent crime and workplace fatalities.

But even as the country inches forward, we’re falling farther and farther behind the rest of the developed world. “For nearly all indicators of mortality, survival, and life expectancy,” the report says, “the United States ranks at or near the bottom among high-income countries.” Our infant mortality rate is still three times that of Finland, Sweden or Japan, and our average life expectancies (76 years for men, 81 for women) don’t compare with those of other advanced democracies. Our peers for longevity include Bahrain, Chile, Panama and Cuba.

Why is the richest country on earth such a laggard on such critical measures of human development? From national trends, you might guess that all Americans were getting slowly but steadily healthier. But we haven’t all benefited equally. People’s lives are eight years shorter in poor states than prosperous ones, and the least educated Americans die a full decade younger than the most educated. They also suffer far higher rates of disease and disability. As Catherine Dower of UC San Francisco’s Center for the Health Profession wrote recently, “Life expectancies in some [U.S. counties] are among the best in the world, although people in other U.S. counties can expect to live no longer than people in developing countries.”

Hawaii, America’s healthiest state, outranks Sweden and Switzerland, with an average life expectancy of 83 years. Yet people die younger in Mississippi (with an average life expectancy is 75) than in Libya or Lithuania.

The state rankings show clear regional patterns: Southeastern states tend to cluster at the bottom of the barrel, while the Northeast and Upper Midwest float at the top. But geography isn’t destiny in America. As the new report makes clear, the forces driving our health disparities are ultimately social and economic. What makes Mississippi so different from states like Hawaii, Vermont and Minnesota? The key factors include a high-school graduation rate of just 64% (versus 91% in the top-ranked state), a college-graduation rate of 20% (versus 49% in the highest-ranked state), and a child poverty rate of 30% (versus 10% in the top-ranked state).

The link between education and health isn’t perfectly understood, but there is no better predictor of physical and psychological well-being. Besides enjoying higher incomes, safer occupations and better access to health care, educated people tend to have healthier lifestyles, more tolerance for stress, and a greater ability to manage chronic health conditions. As University of Illinois longevity expert Jay Olshansky wrote in Health Affairs last year, four years of college “yields a pronounced longevity advantage for all racial and ethnic groups”—and “having a postgraduate degree produces an even greater advantage.”

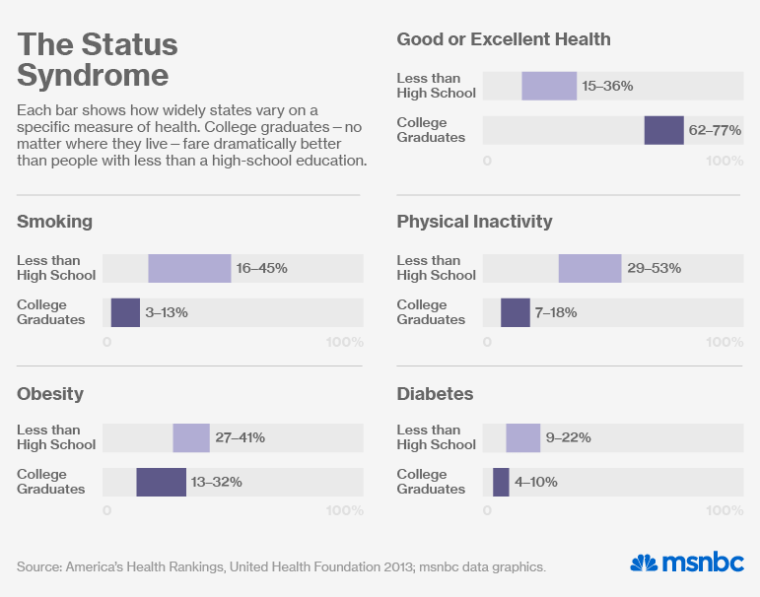

Viewed through this lens, America’s regional challenges come into clearer focus. Mississippi may be the sickest state in the country, Hawaii the healthiest, but college-educated Mississippians are just as likely as college-educated Hawaiians to rate their health as very good or excellent. Nationally, some 68% of college-educated adults rate their health as very good or excellent. The figure is just 22% among adults who didn’t finish high school—no surprise when you look at their risk factors for illness. As you can see from the bar charts above, nearly 30% of them smoke (compared to 8% of college graduates), 42% are physically inactive (versus 12% of college grads), and more than 35% are obese (versus 22% of college grads).

Clearly, it will take more than medicine to heal these divisions. The United States already leads the world in health-care spending and state-of-the-art medical facilities. But it also leads the developed world in social and economic inequality. And as recent reports have shown, health conditions for people with less than 12 years of schooling are actually declining. America’s least educated whites now have life expectancies typical of the 1960s and 70s. And as Olshansky wrote last year, their longevity “is growing worse over time.” White women without high school diplomas have lost five years of life expectancy since 1990, even as those with college degrees have gained three.

“We can’t cure our way out of this,” says Dr. Reed Tuckson, the United Health Foundation’s senior medical adviser. “We need to change the conditions of people’s lives.” In other words, better schools and a fairer economy aren’t just the keys to prosperity. They may also improve our health in ways that health care alone can’t.