President Obama will spend much of the coming week talking about the need to replenish the U.S. Highway Trust Fund. But he won’t propose the simplest and best solution to the problem -- an increase in the federal gas tax.

The Trust Fund, which has paid for the interstate highway system since its creation in 1956, will go broke by the end of this summer, or soon thereafter. The House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee have both passed short-term fixes to keep highway repair funded through next spring, but they can’t agree on funding mechanisms. The House would scare up $11 billion through some accounting gimmicks; the Senate would avail itself of some of these gimmicks, but also tighten up administration of the child care income-tax credit, which House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp rejects, preposterously, as a “tax increase.”

In truth, both the House and the Senate patches avoid using tax increases to restore the Highway Trust Fund to (temporary) solvency—and that’s to neither’s credit. President Obama’s plan is significantly better than what the House and Senate propose. Partly that’s because it reauthorizes the Highway Trust Fund for four years, not eight months, but mainly it’s because Obama’s funding mechanism is less gimmicky. He would pay for the bill by closing business tax loopholes, i.e., raising taxes. The loophole-closings are part of the president’s proposed business tax reform, which would also drop the top corporate tax rate from 35% to 28%.

Unfortunately, even Obama’s revenue source is only temporary, given that over the long term, the business tax plan is projected to be revenue-neutral. It’s also unlikely to get enacted, given the GOP’s polymorphous obstructionism. Even many liberals would shed no tears for the demise of Obama’s business tax reform, arguing that the Treasury should be collecting more revenue from corporate taxes—not the same amount distributed in less opaque fashion—on the grounds that, contrary to popular wisdom, U.S. corporate taxes are actually somewhat low by international standards.

Why not raise the gas tax instead?

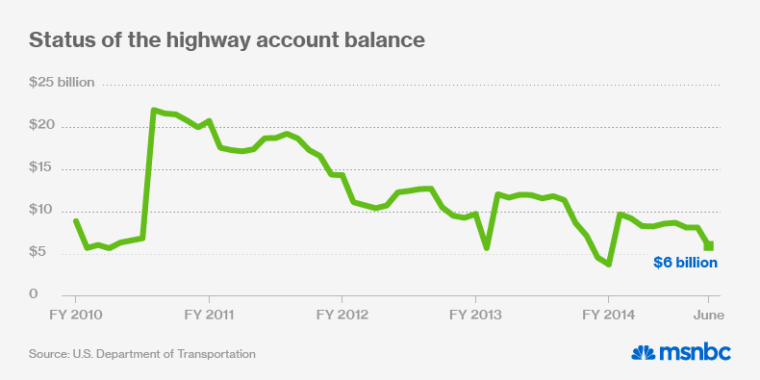

The gasoline tax is supposed to be the sole revenue source for the Highway Trust Fund (along with taxes on diesel and a few other fuel types; a tax on tires; a tax on truck and trailer sales; and a tax on the operation of heavy trucks). But these taxes haven’t been enough to pay for highway repairs and expansions, so starting in 2008, Congress started dipping into general funds. Since then, $41 billion has been transferred from the Treasury to the Highway Trust Fund, with an additional $27.5 billion supplied through President Obama’s stimulus bill.

Why is the Trust Fund going broke? The main reason is that the gasoline tax hasn’t increased since 1993, when Congress raised it to 18.4 cents per gallon in lieu of creating a more broad-based “BTU tax” sought by President Bill Clinton. The cost of roadway construction labor and materials increased by more than one-third over the next two decades while the gas tax stayed the same. Another, perhaps more surprising reason the Trust Fund is going broke is that Americans are buying less gasoline — mostly because the number of vehicle miles traveled fell for most of the past decade (a phenomenon largely but not entirely attributable to the Great Recession and its aftermath) and partly because of gains in fuel efficiency.

Increasing the gas tax would be the best way to address this funding shortfall. Some would argue that the cost of an expensive resource like highways — one that’s being used somewhat less than before — would best be imposed on the users. A better reason, though, is that even with falling gasoline consumption, automobiles remain a worrisome source of carbon in the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. Transportation accounts for 28% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions — the single largest category except for electricity generation (33%). And fully 84% of the greenhouse gases generated by transportation are attributable to cars and trucks.

Granted, the gas tax is somewhat regressive, falling equally on rich and poor at the pump. But it’s not entirely so, given that wealthier people are likelier to own cars, and especially to own expensive gas-guzzling SUVs.

Taxing gas is the simplest and easiest way to control how much of it gets combusted into the atmosphere. That’s why a fair number of conservatives favor increasing the gas tax, including N. Gregory Mankiw, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, and the (ordinarily hyperpartisan) Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer. In Congress, Tennessee Republican Sen. Bob Corker has teamed up with Connecticut Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy on a bill to raise the gas tax to 30.4 cents per gallon over the next two years. That would put the tax about where it would be had it kept up with inflation after the last increase in 1993.

What are we waiting for?