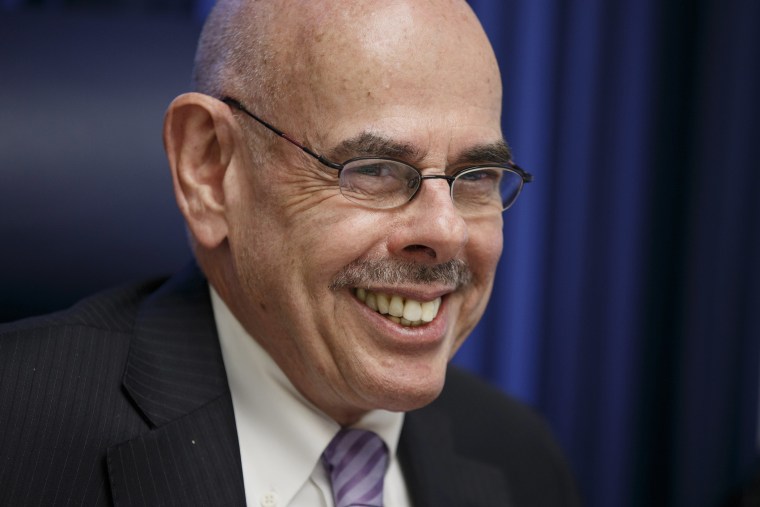

With California Democratic Rep. Henry Waxman’sretirement at the end of the year, three of this era’s five most consequential House Democrats—Waxman, George Miller, and Barney Frank—will be gone. Only Nancy Pelosi and John Dingell (should he decide to run for a 30th term) will remain.

Even that understates the magnitude of Waxman’s departure. For Democrats, it’s the biggest loss of Capitol Hill talent since Ted Kennedy’s death in 2009. In sheer accomplishment, Waxman’s 40 years in the House merit comparison to Kennedy’s 46 in the Senate, especially in the area of public health. Like Kennedy, Waxman distinguished himself by successfully advancing liberal causes even when conservatism was on the rise.

And like Kennedy, Waxman is sometimes criticized for that. National Review’s Jonah Goldberg, for instance, wrote Thursday that Waxman was “a ruthless, mean-spirited, hyper-partisan ideologue” when Democrats were in the majority. But that’s no reason to believe Goldberg would disagree with Washington Post columnist Harold Meyerson’s assessment that Waxman is “a legislative genius.” That’s just true.

“Everything I ever passed into law, with one exception, had bipartisan support,” Waxman told the Washington Post. The exception was the Affordable Care Act, which he helped write -- and which, Waxman pointed out, was “based on a lot of Republican ideas.”

Here are some other accomplishments:

- With Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, Waxman wrote a 1984 law that greatly expanded the market for generic drugs by shortening and simplifying the steps needed to bring them to market.

- The year before, Waxman had been the chief sponsor of a law that streamlined and subsidized development of so-called “orphan drugs,” i.e., drugs for rare diseases that were almost never brought to market. Fewer than 10 such drugs were marketed during the decade prior to the law’s passage. Since then, that number has risen to more than 200.

- Waxman also worked during the 1980s to expand eligibility for Medicaid, which provides health insurance to low-income people.

- A decade later, he helped create the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which extended insurance to children from low-income families that earned too much to qualify for Medicaid.

- The 1990 Clean Air Act -- which was, to a great extent, Waxman’s handiwork -- required him to outmaneuver not only Republican opponents but his fellow Democrat, John Dingell, whose staunch advocacy on behalf of the auto industry (his district is just west of Detroit) had earned him the nickname “Tailpipe Johnny.”

Waxman would eventually succeed Dingell as chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. While chairman of its oversight subcommittee, Waxman presided over a number of high-profile investigations, including the famous one in which seven tobacco company chief executives denied under oath that nicotine was addictive or that cigarettes could lead to lung cancer. In his 2009 book The Waxman Report: How Congress Really Works, Waxman boasts that one aide to a Republican colleague from Virginia ended up disliking him so much that he “had an ashtray in his office with my picture at the bottom for stubbing out his cigarettes.”

After he goes, the void Waxman leaves behind will be hard to fill.