I can’t pretend to know for sure how Romney would have governed. But it’s fair to say that he wouldn’t have been president of Massachu-setts, with an overwhelmingly liberal legislature that had to be ap-peased. Romney would have arrived in office on the tide of a resurgent red state America, with a conservative Republican Congress claiming that its sweeping agenda had been validated by the voters. Embold-ened movement conservatives would have given Romney little room to maneuver on issues ranging from the budget to Supreme Court nominations. He hadn’t stood up to the base during the campaign and would have had a hard time doing so in office without becoming a president without a party.

Amid the cut and thrust of the campaign, I tried to keep the true stakes in mind. Had he won, Romney would likely have had the votes to repeal Obamacare* as promised on Day One (under the same Sen-ate rules requiring only fifty-one votes that led to its enactment). Dur-ing the campaign he pledged to cut federal spending so deeply that it would, as his running mate Paul Ryan put it, constitute “a fundamen-tally different vision” of government. Ryan, whom the Romney transi-tion team had already designated to supervise the budget in a new administration, said that he viewed the social safety net, especially food stamps, as a “hammock” for the needy that was harming the “national character.” The Romney-Ryan budget would have taken a machete to vital investments in the future, from college loans to medical and sci-entific research, while eliminating federal funding for other programs (Planned Parenthood, PBS, Amtrak) entirely.

Even if Democrats blocked some of Romney’s bills, his election would have vindicated the Bush years and everyone associated with booting Obama, from Karl Rove to the Tea Party. It would have given comfort (and jobs) to those who considered climate change a hoax and the war in Iraq a noble cause. With Obamacare and his other achieve-ments reversed, Obama’s presidency might well have been seen by many historians as a fluke, an aberration occasioned in 2008 by a fi-nancial crisis and a weak opponent, John McCain.

As I learned when writing a book about Franklin D. Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, history is usually written by the winners. If today’s recovery continued or strengthened, it would have allowed a President Romney to argue that slashing taxes on the wealthy, slashing environ-mental regulation, slashing programs for the poor, increasing defense spending, and voucherizing Medicare were what led to economic growth. History would have recorded that Barack Obama (like Jimmy Carter) had failed to rescue the economy and Mitt Romney (like Ronald Reagan) had succeeded.

After an election, voters sometimes take the outcome for granted or say it was preordained. See! I was right! I always knew Obama was going to win! Anyone tempted to think this should note that Bill Clinton believed Obama would lose all the way up to the arrival of Hur-ricane Sandy, or so Romney said Clinton told him when the former president called him after the election. With a sluggish economy and a Republican Party backed by billionaires making unlimited campaign contributions, Obama could easily have been a one-term president.

* After the president embraced the term in 2012, “Obamacare” ceased to be a pejorative. I’ve used it for convenience throughout.

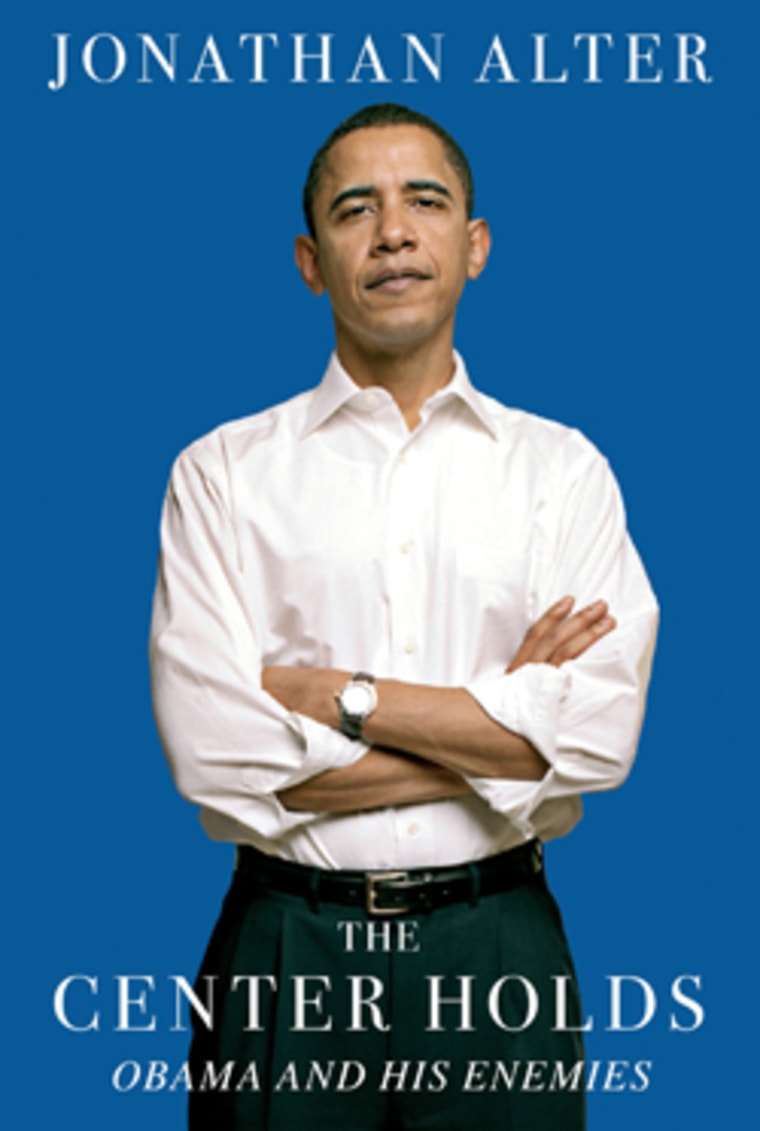

The Center Holds is more than a campaign book and less than a complete history of the second two years of Obama’s first term. My aim is to explain how the president’s enemies sought to wrench the country rightward, how Obama built a potent new Chicago political machine to fight back, and how his, and Romney’s, performance in the 2012 campaign played out against a backdrop of hyperpartisanship and renewed class politics.

All presidents face intense opposition, but Obama’s race and “otherness”—not to mention his longstanding determination to “change the trajectory of American politics”—put him in a different category. He embodies a demographic future that frightens people on the other side. I’ve charted the progression of the malady known as Obama Derangement Syndrome and tried to explain the roots of the antitax and Tea Party uprisings. And I’ve devoted a chapter to what I call “the Voter Suppression Project,” a concerted GOP effort in nineteen states to change the rules of the game to discourage Democrats from voting. Toward the end I explain how the backlash against voter suppression contributed to Obama’s victory.

I’m also fascinated by what I see as a strange role reversal at the heart of the campaign. Romney, the self-described “numbers guy,” re-jected Big Data and ran a Mad Men campaign based on a vague and unscientific “hope and change” theme. Obama ran a state-of-the art “Bain campaign,” using some of the same analytics pioneered in the corporate world to redefine voter contact and build the most sophisti-cated political organization in American history.

The 2012 cycle will likely be seen as the first “data campaign.” Just as Franklin Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy have been viewed by histo-rians as the first presidents to master radio and television, respectively, Barack Obama will likely be seen as the president who pioneered the use of digital technology that, in various forms, will now be a perma-nent part of politics around the world.

Like my 2010 book, The Promise: President Obama, Year One, this account draws on my Chicago roots. I met Obama there when he was an Illinois state senator who had recently lost a bid for Congress. In the years since, I haven’t lost my fascination with the paradox of a man succeeding so spectacularly at a profession that he often dislikes. He is missing the schmooze gene that is standard equipment for people in politics. In the Washington chapters, I try to assess the consequences of this for his presidency.

The Promise was focused on Obama’s governing, the part of the presidency that he likes best. The Center Holds has some of that (e.g., new details about the killing of Osama bin Laden and the Supreme Court battle over Obamacare), but it is mostly about politics. Obama knew as early as mid-2010 that almost nothing substantive would get done for the next two years as the country chose its path.

I’m focused here on detailing the backstory of the big events of 2011 and 2012. This is a work of reporting, chronicling everything from Roger Ailes’s paranoid behavior to the geeks in the secret Chicago “Cave” who built crucial models for the Obama campaign to the car ac-cident in the Everglades that helped motivate a South Florida bartender named Scott Prouty to videotape Romney talking about the “47 per-cent.” While I’m not sure I agree with David Axelrod that campaigns are “MRIs of the soul,” I hope to provide a few X-rays.

“Contemporary history” is a genre fraught with peril. Some events will shrink in significance over time, while others I underplay or miss entirely may end up looming large. Passions have not yet cooled, and the story of Obama contending with his enemies remains unfinished. It would be dishonest for me to pretend to be neutral in this contest. But all good history has a point of view. The important thing is that it be written under the sovereignty of facts, wherever they may lead.

In 2011, when it looked as if Obama might lose the presidency, a friend asked me to explain how such a thing could happen. Where did Grover Norquist come from? I told her I wasn’t sure Obama would lose—that it could go either way—but I would try to tell a story of this moment in our national life that didn’t neglect the historical context. So I write in the past tense and stud the narrative with bits of relevant his-tory that are integrated into the text rather than relegated to footnotes. Franklin Roosevelt ordered the killing of a single enemy combatant; John F. Kennedy confronted right-wing haters; and Richard Nixon ran a TV ad mentioning “the 47 percent.” As Mark Twain (supposedly) said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

The arguments of 2012 go back to the dawn of the republic, when Thomas Jefferson stressed limited government and Alexander Hamilton championed a strong nation investing in its people and future. Obama’s themes are those of the great twentieth-century progressive presidents, from Theodore Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson. Romney and the conser-vatives in Congress are ideological descendants of those who opposed the New Deal and the Great Society and saw the business of America as business. I’ve used my reporter’s notebook to update these historical cleavages.

If the 2012 campaign had merely contained the natural tension in American history between individualism and community, it would not have been so extraordinary. Something more profound was at stake. E. J. Dionne wrote in his book Our Divided Political Heart, “At the heart of the American idea—common to Jefferson and Hamilton, to Clay and Jackson, to Lincoln and both Roosevelts—is the view that in a democracy government is not the realm of ‘them’ but of ‘us.’ ” The radical right that would have been vindicated and emboldened by a sweeping Republican victory sees the government as “them.” I make no apologies for suggesting that the United States dodged a bullet in 2012 by rejecting this extremist view of our 225-year experiment in democ-racy. We are a centrist nation and will remain so.

Writing history in real time has its advantages. What’s lost in perspective is gained in finding stories and insights in their messy original state, before time and selective memories turn them neatly into pleas-ing myth. But in some respects, as the U2 song played at Obama campaign rallies goes, “The more you see, the less you know.” I remain in what the Harvard historian and president Drew Gilpin Faust calls “the grip of the myopic present.” I hope to have broadened my vision enough to see a few things that others missed. Where I haven’t, there is no one to blame but me.

Jonathan AlterMontclair, New JerseyApril 2013