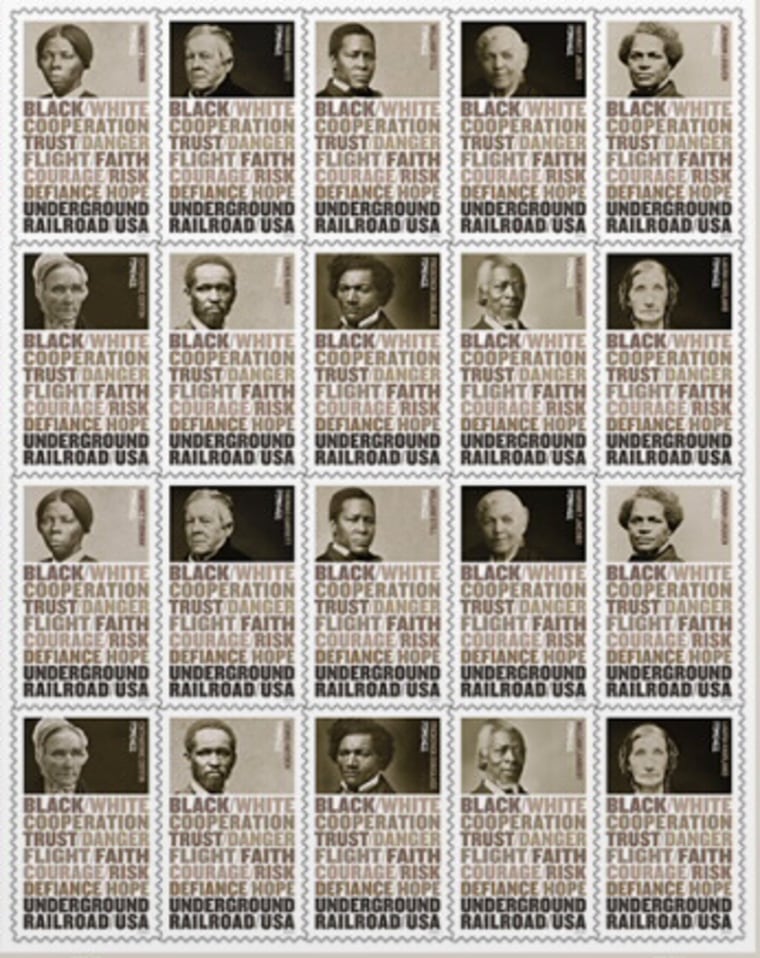

The United States Postal Service is releasing today a series of stamps honoring “10 of the heroes of the Underground Railroad,” a network of activists who helped 19th-century African Americans obtain freedom when keeping human beings and their descendants enslaved for life was the law of the land. The 10 people being commemorated are Harriet Tubman, William Still, Thomas Garrett, Laura Haviland, the Rev. Jermain Loguen, Catharine Coffin, Lewis Hayden, William Lambert, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs.

“Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” left an indelible mark on American literature.

As a professor who has studied Jacobs’ life and edited the 2023 edition of her autobiography, I find it especially appropriate that she, who wrote the first book-length memoir by a formerly enslaved African American woman, is one of the 10 people featured in the “Underground Railroad” series. It’s especially fitting because USPS’ representation of the Underground Railroad’s collective and communal character aligns with how Jacobs lived her life and how she wrote “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” a book that left an indelible mark on American literature.

At a time when the accurate teaching of history is under attack, when acknowledging a range of lived experiences gets mocked as “woke,” and when some politicians suggest the U.S. has never been a racist country, it’s heartening to see the USPS highlighting Americans who saw the evil of racism and fought against it. At a time when women feel less autonomy over their bodies, it’s particularly gratifying to see the USPS series feature Jacobs — who went to remarkable lengths to assert autonomy over hers.

Despite laws that made literacy illegal for the enslaved, Frederick Douglass made a point to emphasize that his 1845 autobiography, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,” was “written by himself.” Following suit, Jacobs declared her 1861 story to be “written by herself,” but her narrative stands out in U.S. history and literature because it put forth a narrator like none before. While Douglass had shared the terror of watching his aunt be beaten because her enslaver wanted to control her sexually, Jacobs’ narrative is what Douglass’ aunt might have written. “Slavery is terrible for men,” Jacobs wrote, “but it is far more terrible for women. Superadded to the burden common to all, they have wrongs, and sufferings, and mortifications peculiarly their own.”

James Norcom, the man who enslaved Jacobs, began sexually harassing her when she was 15. By law, any children she had would be Norcom’s property; he could enrich himself by raping her. To frustrate his plans, she relied on family members and white accomplices, some of whom were enslavers themselves, and that remarkable cooperation empowered Jacobs to hide for nearly seven years while only a block away from her tormentor. That’s why I’m convinced Jacobs would appreciate the emphasis the postal stamp series places on “Black/White Cooperation.”

Cooperation among Black and white Americans was an undeniable part of Jacobs’ story as well as the history of the Underground Railroad. Remembering that fact should spark some optimism for the fights we now face: For example, preventing Project 2025, the Republican plan for making every government agency serve a king-like president, requires concerted, coalitional effort.

In the autobiographies that Douglass and other Black men wrote, the narrator emerges as a singular figure. The narrator typically distinguishes himself from those who were enslaved around him. It was his unique qualities that enabled him to conquer adversity, to become the person who freed himself. “Incidents” rejects those masculine storytelling patterns and is relayed by a narrator who was uninterested in escaping solo (without her children) and who reveals how much she relied on family members, friends and, again, even people who were enslavers.

Slavery is terrible for men, Jacobs wrote, but it is far more terrible for women. Superadded to the burden common to all, they have wrongs, and sufferings, and mortifications peculiarly their own.”

Harriet jacobs, "incidents in the life of a slave girl"

While the story of the Underground Railroad should inspire optimism, the stamps celebrating its history should remind us of the racial and sexual oppression that persists and must be challenged. A Thursday poll from KFF (which focuses on health policy research) found that 28% of Black women say abortion is "the most important issue" heading into November’s elections.

“It’s a complete shift,” Ashley Kirzinger, a KFF pollster, told The Associated Press about the poll. “Abortion voters are young, Black women — and not white evangelicals.” The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022. However, some officials aren’t content with abortions being outlawed in their states. They’ve threatened to imprison people who, in the spirit of the Underground Railroad, are helping women travel to states where they can have such procedures. I find it poignant, then, that on each “Underground Railroad” stamp, we see the words “Trust/Danger” and “Defiance/Hope.”

The ongoing backlash to our individual freedoms makes Harriet Jacobs’ story all the more relevant. Her narrative is full of clarity about how adapting to injustice keeps shaping our reality. But, in community with the other “heroes of the Underground Railroad,” Jacobs calls on us to notice how much defiance, hope and cooperation across our differences is required today.