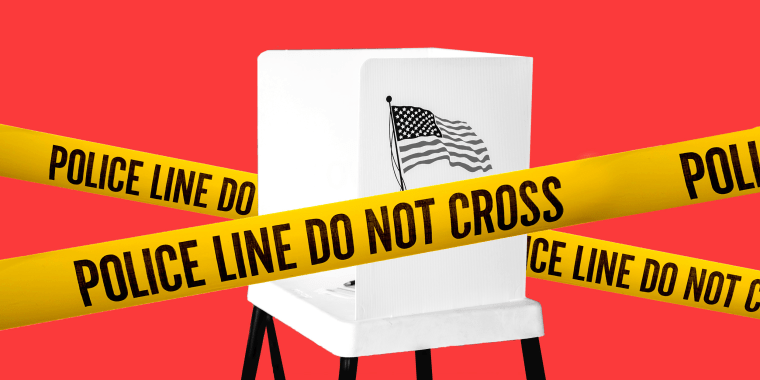

Republicans in multiple states are pushing a new tactics and programs to tackle the mythical problem of voter fraud: election police.

In Florida, Georgia and Texas, Republicans have passed new policies and laws that have created costly new infrastructure and enforcement mechanisms to crack down on what they claim is voter fraud, despite the fact that there is no evidence that voter fraud is remotely serious problem in our democracy or in need of additional surveillance.

The new trend reflects how the GOP’s political stunts about election integrity are taking on a life of their own.

These programs are, at the very least, wasteful. But they could also potentially dampen voters’ inclination to enter the voting booth out of fear that making some kind of mistake in casting their ballot could be severely penalized. And over the longer term, gimmicky voter fraud enforcement bureaucracy could help foster rising authoritarian sentiment on the right by lending more weight to the idea that Democratic electoral wins should be met with suspicion.

The new trend reflects how the GOP’s political stunts about election integrity are taking on a life of their own. Former President Donald Trump’s disinformation campaign about the 2020 election being rigged has not only created enduring false narratives about an insecure voting system — it has also spurred the creation of a set of new institutions to address a problem that doesn’t exist.

The New York Times has reported on some of the latest developments:

The Florida Legislature last week created a law enforcement agency — informally called the election police — to tackle what Gov. Ron DeSantis and other Republicans have declared an urgent problem: the roughly 0.000677 percent of voters suspected of committing voter fraud.

In Georgia, Republicans in the House passed a law on Tuesday handing new powers to police personnel who investigate allegations of election-related crimes.

And in Texas, the Republican attorney general already has created an “election integrity unit” charged solely with investigating illegal voting.

One of the most obvious issues is that these programs require state governments to invest money, personnel and institutional resources to address a phantom problem. Texas’ voter fraud crackdown efforts last year required spending more than $2 million, and 20,000 hours of labor to close three cases and open seven new ones. Those kinds of resources would be much better spent on a problem that actually exists or threatens our democracy.

There is also rising concern among voting rights advocates that increasing attention to aggressive enforcement could dampen voter participation. Will the exceedingly rare instances of fraud, which are committed accidentally a significant amount of the time, be punished with much more severe penalties? For example, if voters are confused about where exactly they’re registered to vote or allowed to register to vote because they moved recently or they’re between addresses, a fear of enhanced penalties could convince some that voting is not worth the effort. There's reason to think that these problems are disproportionately likely to discourage voters who have fewer resources and hail from marginalized communities, because they tend to have less information as voters and can't afford risking financial penalties.

There are also questions about the exact purview and power of these new units. “I really think we have a lot of procedures in place where these things can be addressed, and I worry that we’re putting in place a police force which has no guardrails,” Florida state Sen. Lori Berman, a Democrat, told The Associated Press about the new election police unit in her state. “We don’t know who can initiate the investigation, there’s nothing to prevent it from being used for targeting certain groups, and I really worry about us having this kind of squad that’s totally out there without any supervision.”

Finally, it’s worrying to contemplate how these policies will allow the Republican political class to continue to mislead its voter base into thinking voter fraud is indeed a real problem. Some Republican voters might hear of these policies and think to themselves, “Surely if they’re creating entire new police units for this thing, it’s got to be pretty serious, right?” Unfortunately, some of them likely underestimate the cynicism of the leaders of their own party.

The money spent on new election police and associated programs is better spent on funding to administer elections properly — and solving problems that actually exist.