MANDERSON, South Dakota — In almost any other context it would be a given, an expectation as simple as a dark cloud spitting rain. But when 12-year-old Carleigh Campbell tested proficient on the South Dakota achievement test last year, it was a rather astonishing feat.

Campbell is a student at a school where four students have attempted suicide this year alone. Roughly four out of five of her neighbors are unemployed and well over half live in deep poverty. About 70% of the students in her community will eventually drop out of school.

"I always think about how it could be happier. I think lots of people aren’t happy here. I always think I can cheer them up, so I try."'

It’s against this backdrop that Carleigh met expectations on the state's mandated exam, the only student out of about 150 in her school to do so. To state the obvious, Carleigh’s academic achievement is a bright spot in an epically dark place.

Carleigh is a Native American sixth grader at the Wounded Knee School located on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, where a well-documented plague of poverty and violence has festered since the Oglala Sioux were forced onto the reservation more than a century ago. There is virtually no infrastructure, few jobs and no major economic engines. Families are destabilized by substance abuse and want. Children often go hungry and adults die young.

These realities wash onto the schoolyards here with little runoff or relief, trapping generations of young people in hopelessness and despair.

“We’re in an urgent situation, an emergency state,” said Alice Phelps, principal at the Wounded Knee School. “But underneath all the baggage is intelligence, potential, and these children all have that.”

Few communities in America are as eager for a silver lining as the Lakota of the Pine Ridge reservation, situated on more than 2 million rambling acres, nudged up against the Black Hills and Badlands National Park. Nowhere is it more palpable than in the reservation’s schools, a jumble of public, private and federal systems that often overlap but rarely ever bolster the academic prospects of the most forgotten children in America.

While the 565 Native American tribes recognized by the U.S. government enjoy sovereign status as separate nations, nearly all Indian education funding is tied up with federal strings. Unlike most public schools that rely largely on local tax money, there are virtually no private land owners on the reservations, so no taxpayers to tax. The government often pays as much as 60% of a reservation school’s budget compared to just 10% of the budget of a typical public school. When last year’s federal sequestration cuts kicked in, Indian country was hit first.

The government is starting to own up to its failures. In a startling new draft report released in April by the federal Bureau of Indian Education, which oversees 183 schools on 64 reservations in 23 states, the agency draws attention to its own inability to deliver a quality education to Native students. BIE-funded schools are chronically failing and “one of the lowest-performing set of schools in the country,” according to the report.

“BIE has never faced more urgent challenges,” the report said. “Each of these challenges has contributed to poor outcomes for BIE students.”

During the 2012-2013 school year, only one out of four BIE-funded schools met state-defined proficiency standards, and one out of three are under restructuring due to chronic academic failure, according to the report. BIE students performed lower on national assessment tests than every other major urban school district other than Detroit Public Schools, the report says.

BIE students also perform worse than American Indian students attending regular public schools. In 2011, 4th graders in the BIE scored 22 points lower in reading and 14 points lower in math on national proficiency tests than their Indian counterparts attending public schools.

BIE schools are typically located in some of the poorest, most geographically isolated regions of the country. Four of the five poorest counties in America are located on reservations. Shannon County, where Pine Ridge is located, is the second poorest with a per capita income of just $6,000-$8,000 a year. It’s also extremely difficult to attract quality teachers willing to relocate to remote outposts with limited quality housing and extreme quality of life issues.

The BIE blames its failures on “an inconsistent commitment from political leadership,” institutional, budgetary and legal barriers as well as bureaucratic red tape among federal agencies. Those systemic issues have produced a disjointed system that has even clogged up the delivery of required materials, including textbooks.

The BIE has had 33 leaders in 35 years, making a chaotic system that has not operated efficiently for decades even worse.

Dr. Charles Roessel, director of the BIE, told msnbc that the agency is actively consulting with tribes across the country to identify ways the bureau can help tribes bolster the academic outcomes of their students. The draft report was the product of those consultations.

Some challenges are obvious. “How do you get a quality teaching staff at a very remote part of the country where you don’t have a city to support or you don’t have the infrastructure and the salaries are lower?” Roessel said, adding, “The greatest impact in a classroom is the teacher and we need to improve the quality of that instruction. And we have to do it with our hands tied behind our back and our feet tied together, too.”

Never Gave Up Sovereignty

Poor academic performance plagues American Indian students both on and off federal lands.

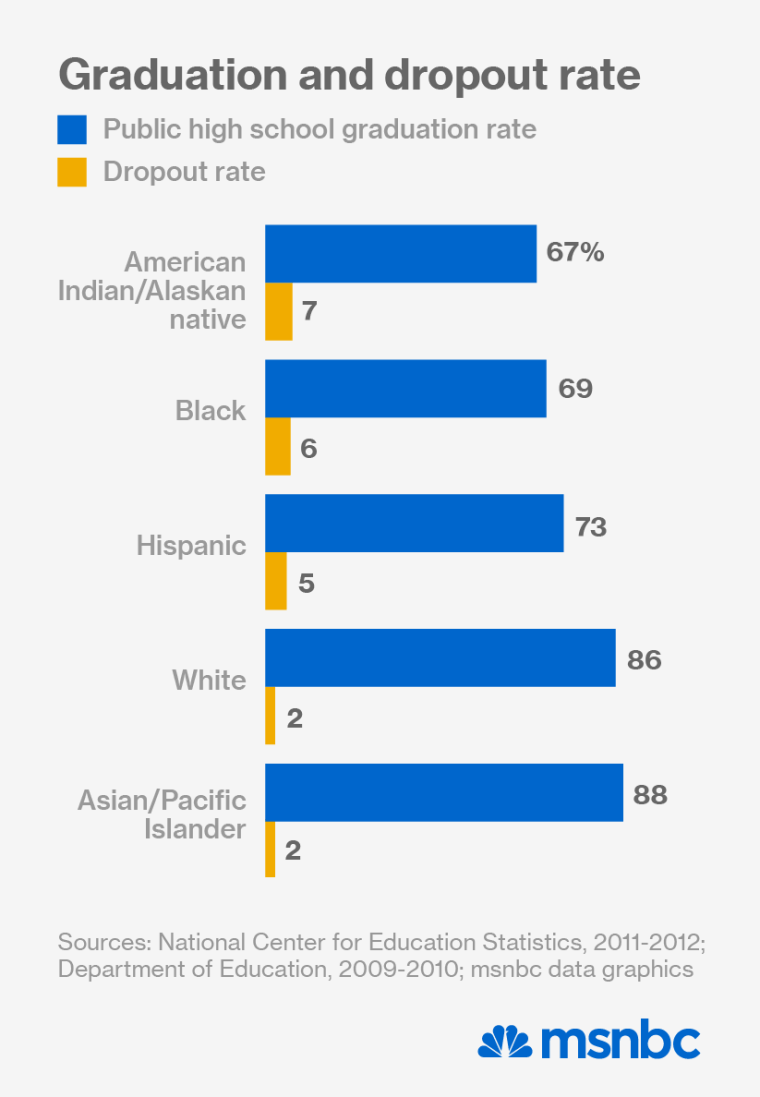

Even as other historically oppressed minority groups like African Americans and Hispanics have made steady academic progress over the last decade, achievement among American Indian youth has stalled. Huge spikes in black and Hispanic high school graduation rates have pushed the country’s overall graduation rate to an all-time high, while the rate for Native American students is trending in the opposite direction.

Compounding the poor academic outcomes is what advocates in Indian country describe as a history of broken treatises, lingering racism and chicanery.

While tribes operate some of the BIE schools, the funding comes with various restrictions and benchmarks. And in the case of traditional public schools that operate near reservations and have a large number Indian students, funding goes directly to states and does not provide culturally relevant Indian education.

"The central offices, they take their big cut out and they have everything, so by the time it gets to our children there’s very little money left and that’s one of the big problems," Bryan Brewer, president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, said on a recent afternoon during a town-hall style meeting between tribal members and BIE officials. "We don’t have enough money for facilities. If we need to buy something, a furnace, something like that, we have to cut out a teacher. It’s that bad."

The economic and political implications are worst in states with the largest populations of American Indians, including New Mexico, Montana, Oklahoma and South Dakota.

“There are challenging state and tribal dynamics. There’s history involved here and the reality of sometimes incompatible bureaucracies, the lack of capacity and understanding of one another and even alternative goals,” said William Mendoza, the executive director of the White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native Education. “The experience has been one of a history of tragedy where the effort, both real and perceived, was to assimilate American Indians.”

The ghosts of bygone eras when Indian students were forced into boarding schools, had their hair forcibly cut and were often beaten for speaking their native languages, continue to haunt Indian Country.

“Those dynamics affect decision making and the reconciliation as they’ve communicated to us has not been fully realized in some communities throughout the country,” said Mendoza, a Lakota who for years taught language arts on the Pine Ridge reservation.

Ahniwake Rose, executive director of the National Indian Education Association, called the tangle of systems tying up the education of Native youth “a web of confusion” and the lack of adequate funding to schools “a direct violation of treatises.”

"We’ve got to all live together so let’s get our education and do what we can to improve our people, improve our livelihood, to improve our future because you can’t depend on the government."'

“Tribes never gave up the sovereignty of the education of their students. Native people are the only people in the country that there’s a federal obligation to educate. It’s in the constitution and in all of our treatises that the federal government provides our education. Everyone else’s education is mostly a state rights issue,” she said.

The widespread failures have left countless Native American students trapped in an all too familiar cycle of poverty, violence and substance abuse. And they’re almost wholly unable to access a quality education, the surest path into the middle-class.

The abysmal state of education on the Pine Ridge reservation has sparked a renewed interest in wresting back control of educating its youth. Language immersion programs have been launched. An all-girls school is being planned. Some groups are pushing for state charter school legislation to allow for largely autonomous start-up schools.

And there’s been new momentum around crafting more culturally relevant curricula for young Indians who’ve largely lost their spiritual and historic connections to the rich history of the Lakota, members of one of the seven subtribes that make up the Great Sioux Nation.

“The tribe has not had a say in how our children will be educated and we’re standing up,” Brewer said. “Let us decide what our children will learn, how they will be educated because the BIE, they haven’t been successful at all.

He added, “Just give us some money and we’ll do it.”

Lots of People Aren’t Happy

On the best of days, Carleigh Campbell puts on a smile and tries her hardest to lose herself in a whir of homework and class projects. A wisp thin girl with dark hair pulled into a loose pony tail, Carleigh’s a worker bee: studious, helpful, outgoing and intentional.

“At times life will be tough but other times, if I’m not thinking about what makes it tough, it just gets easier,” Carleigh said on a recent morning between classes at the Wounded Knee School. “I don’t really spend very much time worrying if I’m focused on something else.”

But the little girl isn’t immune to the generational curses that afflict so many in this place. Her mother battles alcohol addiction and is estranged from the family and Carleigh’s hardworking, single-father. And at age 12, the pressure on Carleigh to be a good enough student to make it to college and off the reservation one day can be daunting.

On the worst of days she turns to schoolwork to keep from being overwhelmed by worry and fear: Worry that her mother’s drinking will tear her family further apart. And fear that it might spread to her older siblings, sinking them into the kind of self-destruction that has consumed so many others here.

Sometimes she cries, but mostly she just dreams about how life on the “rez” could be.

“I always think about how it could be happier. I think lots of people aren’t happy here. I always think I can cheer them up, so I try,” she said.

Carleigh’s father, who works as a teacher’s aide at the school, said he’s inspired by all of his children for their perseverance, especially Carleigh, his youngest.

“They give me a reason to keep on keeping on, you know,” Ron Campbell said. “I think I’m doing okay and I just want my kids to do better than me. I mean, that’s what I tell them every day, just do better than me. I don’t care if you want to live here or not, but just do better.”

Growing up on Pine Ridge, Campbell said suffering is woven into nearly every part of daily life. The life expectancy is just 48 years old for men and 52 for women. The obituary sections of tribal newspapers are dotted with young-ish looking faces. As a teenager, Campbell lost nearly 10 friends to violent deaths, either by suicide or drunk driving.

He’s one of the few who went away to school, came back, and found meaningful employment.

“We’re all on our own here,” he said. “I mean, it’s kind of bad, you know. I know a lot of my friends and everything, they haven’t had work in who knows how long. And they just try to scrape by with government assistance and whatever.”

Educating children in this environment is extremely difficult, he said. Inexperienced teachers at the school, non-Indians mostly from faraway worlds that most of the kids can’t even imagine, don’t often have the cultural competency to unpack the complexities of the students’ lives.

“I try to help these new teachers come and understand that, you know, when there’s a kid that comes and they have an attitude or something like that or they’re not listening or they don’t want to do the work, it’s because maybe they’re hungry or maybe their head’s full of bugs and it’s driving them nuts or something like that,” Campbell said. “A lot of these new teachers come from good families, you know. They expect a certain level and that’s good. They should expect it. But at the same time they slept and ate good last night.”

Wounded Knee principal Alice Phelps, who spent many of her formative years on the reservation with her Lakota mother, said she’s gotten creative about trying to meet the great needs of her students. She’s implemented a tighter schedule and extended the school day to squeeze more instruction time out of the day. She’s been meeting with parents to urge them to take a more active role in their kids’ school lives. And in recent weeks, Phelps said she announced that there’d be a shake-up of the entire teaching staff to improve the quality of instruction offered at the school.

Phelps said the time for excuses is over.

“You cannot look at yourself as a victim. You’re not a victim. You got to empower yourself and rise above and get educated,” she said. “We’ve got to all live together so let’s get our education and do what we can to improve our people, improve our livelihood, to improve our future because you can’t depend on the government.”

More Successful and Stuff

Carleigh Campbell wants to be one of the ones who makes it. She dreams of going away somewhere to a big college in a big college town, where the buildings gleam and successful people crowd businesses the way people on the reservation crowd in crumbling trailers.

“Because here there’s not very much people around, and if I go to a bigger city there’s more people that are like more successful and stuff, and I guess they’ll help me,” Carleigh said. “But I think I should come back here and help out some. Because lots of people here are struggling and I think over time, it’s probably going to get worse, so it think I should just come back and help.”

Editor’s note: This is the first of three stories on Pine Ridge, exploring the education, social and economic issues facing Native Americans on the reservation.