When I mourned the loss of seven loved ones in the last two years, I only took bereavement leave for two of them. I felt reluctant to ask for this benefit, fearing its impact on my colleagues and career trajectory.

The time for grieving the loss of a loved one has no timeline and no formula, but is often, sadly, not required, unenforced, and unpaid.

No federal law mandates employer-provided bereavement leave, and only a handful of states (California, Illinois, Maryland, Oregon, and Washington) have implemented bereavement leave legislation that offers some degree of support during these trying times. So, I continued to show up to work, sometimes through the haze of tears.

The fear of professional repercussions and societal pressures to prioritize work over well-being underscore the urgent need for bereavement leave reform. My reluctance to take the leave afforded to me is not an indictment of my employer — we have a very generous leave policy — but not all women in the workplace have adequate access to leave.

My reluctance is a commentary on my conditioning that exposes a tendency toward self-sacrifice over self-care and workplace productivity over well-being. Far too many women in the workplace identify with this conditioned behavior. I feared that no matter the reason, time away would erode the perception of my reliability or effectiveness.

Recognizing bereavement as a part of workplace culture

Employers would do well to create a different culture surrounding loss. After all, the Grief Recovery Institute estimates that “hidden grief” (grief that goes unacknowledged or invalidated by social norms) costs U.S. companies more than $75 billion each year.

According to Bloomberg, “The average bereavement leave policy grants an employee three to four days off for the loss of an immediate family member, like the employee’s spouse, and less time for the loss of extended family or friends.” Mercer’s Survey on Health & Benefit Strategies for 2024 reported that 69 percent of employers offer paid bereavement leave and showed a marginally more generous median of five days.

Another recent finding noted that “only 44 percent of companies offered non-consecutive leave.” That’s a leave structure that can be taken at various times throughout the year. According to that report, “this type of leave reflects the reality that grief is a non-linear process that often comes in waves.”

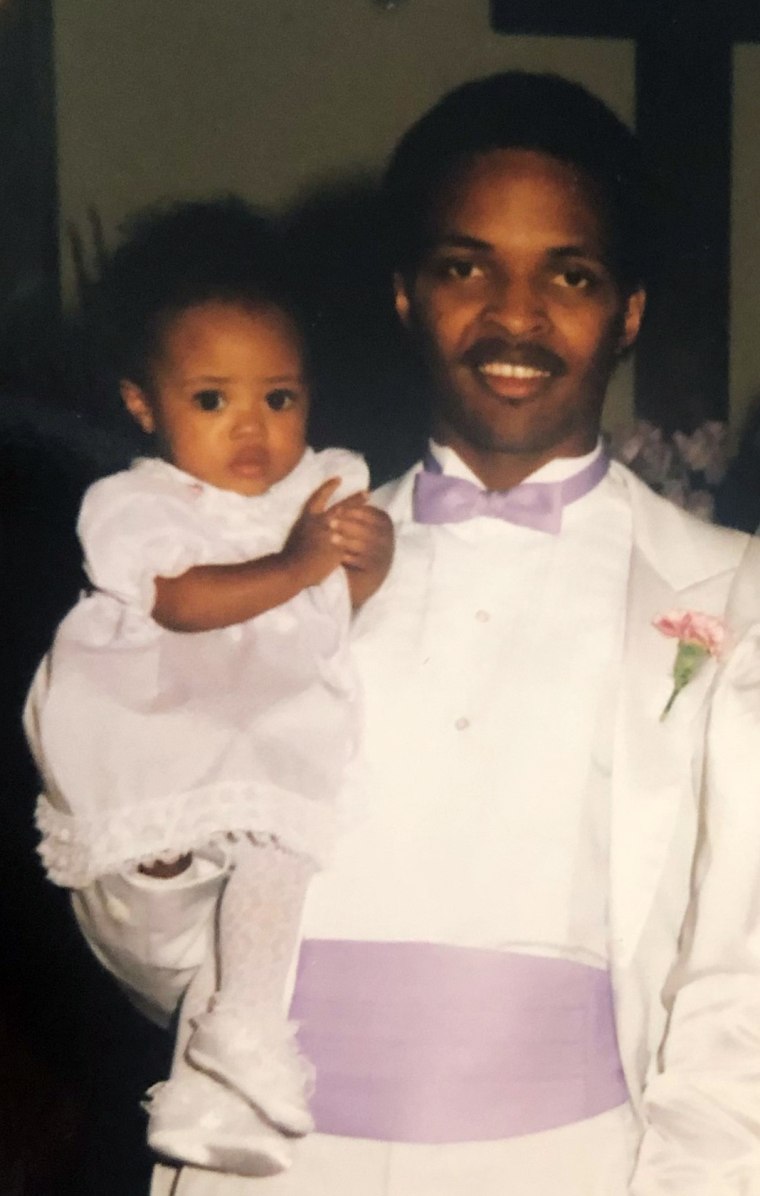

Furthermore, the loss of an “immediate family member” versus the loss of an “other” by company standards is arbitrary, however the impact of that loss is anything but arbitrary. Among my seven loved ones who passed away recently, only one was defined as “immediate family.”

My aunt passed in a violent car crash this year. She’s not considered “immediate family” by employee handbook standards. She lived across the street from me for over a decade and played a pivotal role in my upbringing. I probably spent as much time at her house with my cousins as I did in my own.

How was I supposed to compartmentalize my grief into a shorter period reserved for “other”? How do you process the news, inform others, make arrangements, address legal and financial issues, have a funeral, and find time to cry for a pivotal figure in your life in five days or less?

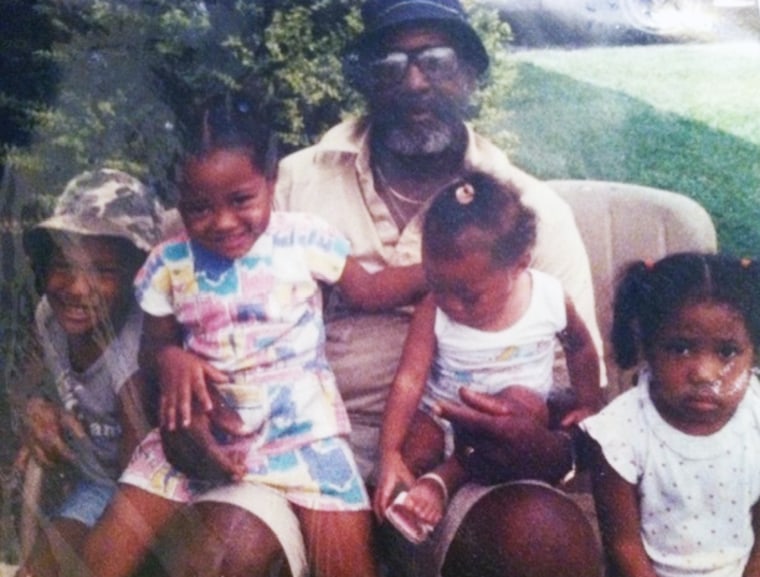

I was faced with the dilemma once more when my grandfather passed unexpectedly. He was considered “other,” too. It was 2:00 a.m. on the last Monday in February. Later that morning, as I balanced the emotions of losing my grandad so soon after the passing of my dad, the idea of taking leave and the fear of repercussions and perceptions washed over me.

I dialed the number for the Pep Talk Hotline as tears pooled on my phone screen. I first discovered this resource as a public art project by kindergarteners after my dad passed. I dialed the number, listened to the instructions, pressed #2 for “words of encouragement,” then dialed again and pressed #4 to “hear kids laughing with delight.”

A pep talk was exactly what I needed at that moment, but it was not a replacement for the time to grieve that I knew would be too short.

Too many women are forced by our workplace cultures and societal norms to rely on momentary pep talks to weather the storm when time is the resource we most require.

Women, often the de facto caregivers in their families, are impacted more than most. Every year, LeanIn.org and McKinsey release a "Women in the Workplace" study that helps leaders understand the needs of professional women.

The most recent study found that “a quarter of women report bereavement leave as a top employee benefit, even over parental leave and childcare benefits. Companies that fail to offer it risk losing valuable talent that they are already likely lacking or striving to retain.”

As a nation, we’ve spent the better part of the last 50 years progressing a gender revolution of “feminism for all” and fighting for women’s rights to participate in every space.

Yet, participation requires a give and take — and women still do the majority of the giving. Nearly 60 percent of women still bear the overwhelming burden of household chores and caregiving. Despite perceived progress, traditional gendered roles within households remain a pervasive expectation, leading to women conceiving, planning, and executing most domestic tasks. In marriages across the U.S. where the wife is the primary breadwinner, she earns more than 60 percent of the couple’s combined earnings, yet has 3.5 fewer leisure hours than her partner. This constant burden means that time, even to grieve, can feel out of reach for us.

How to build bereavement into workplace culture

The ability to take bereavement leave requires a multi-pronged approach. Firstly, more time off is the most obvious step. Five days off is perfunctory, not generous. Next, redefine who is included in one’s “immediate family,” to also include “immediate loved ones.” That is paramount because our grief extends to our chosen family, and their loss is no less felt.

For women in the workplace, paid bereavement leave is the most supportive approach, especially as we continue to grow as sole or primary breadwinners for our families. And finally, we must create space to actually allow people to move through the process of grief by offering increased mental health benefits and prioritizing mental health awareness. Grief is an incredibly vulnerable time that comes in waves, and expanded employee assistance offerings can positively impact engagement and productivity.

The issue of bereavement leave transcends workplace or federal policy; it strikes at the heart of societal values and workplace culture. My experiences, while deeply personal, reflect a broader trend that demands attention and action. It is time for a cultural shift where the need for grieving is acknowledged and supported, regardless of gender or familial relationship. Employers must recognize that productivity should not come at the cost of employees’ well-being, but that the quality of their employees’ well-being, in fact, drives productivity. It’s about time we redefine what it means to support our colleagues during their most vulnerable moments.

Legislation and workplace policies are essential, though true change requires a collective effort to challenge ingrained norms and biases. We need to work toward a future where taking time to grieve is not a luxury but a fundamental right, a necessary part of the human experience.

No one should grieve alone or feel the need to “grin and bear it” for productivity’s sake, prioritizing unrealistic workplace expectations over personal well-being. Our willingness to expand bereavement leave speaks to our values as organizations and who we aspire to be as a society.