It’s far too soon to make any predictions. But a recent decision by a federal judge in the challenge to Texas’s harsh voter ID law may augur well for the chances of getting the law struck down when it goes to trial in September.

Overturning the law would be a massive win for the Obama administration, which is spearheading the challenge, and could boost Democrats’ long-term hopes of competing in Texas. It would be an embarrassing defeat for Gov. Rick Perry and for Attorney General Greg Abbott, who is highlighting his defense of the law as he runs to succeed Perry as governor.

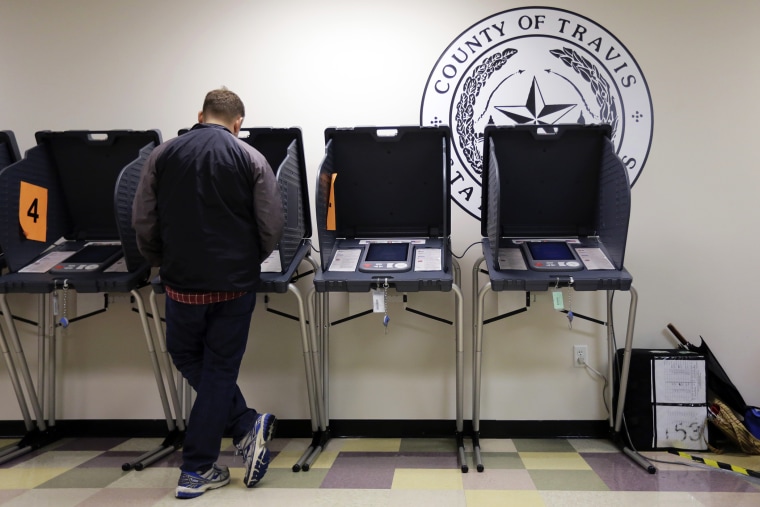

The law, passed in 2011 with strong support from Perry, imposes the strictest ID requirement in the nation. It requires that Texans show one of a narrow range of state or federal IDs. Gun licenses are accepted, but student IDs, and even out-of-state driver’s licenses, aren’t.

Finding that it would disproportionately affect minority voters, a federal court blocked the law in 2012 under the Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required the state to get federal approval for its voting laws. But hours after the Supreme Court invalidated Section 5 last year, Abbott announced that the law would go into effect. The U.S. Justice Department, joined by civil rights groups including the NAACP and groups representing Hispanics, then filed a new challenge to the law under a different section of the Voting Rights Act.

Abbott has responded defiantly. “Eric Holder is trying to stop Texas from enforcing our voter identification law,” he frequently says on the campaign trail. “Voter fraud is real, it must be stopped, and I will take my case all the way to the Supreme Court.”

If the law stays in effect, it could give Republicans an electoral edge going forward, including this fall when Abbott will take on Democrat Wendy Davis. It’s hard to say how many voters will ultimately be disenfranchised by the ID requirement. But by one estimate, one in ten Texans—disproportionately non-whites—lack any of the forms of ID that the law accepts. An aggressive effort by Democrats and their allies to register new voters—many of whom are Hispanic—as they look to make the Lone Star State competitive means the law’s impact in keeping people from the polls could be especially large.

But last week’s ruling, in which U.S. District Court Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos denied almost all of a set of motions filed by Abbott's office to dismiss the case before it goes to trial, suggests that keeping the law in place won’t be a slam-dunk for the AG and his allies.

To be sure, the ruling itself wasn’t a surprise—and election law experts caution not to read too much into it. All Ramos did was give permission for the law’s challengers to make their case, as any good judge would have done, they say. The final ruling, of course, will come down to whether the plaintiffs can present facts that prove that case during the trial, scheduled to start September 2.

Daniel Tokaji, a law professor at the Ohio State University, said some of Texas’s arguments “don’t pass the laugh test,” so it makes sense that Ramos didn’t give them the time of day.

But the approach taken by Ramos, an Obama appointee—and in particular, the unequivocal way in which she rejected Texas’s effort to narrow the scope of federal voting protections—suggests the trial could play out on favorable terrain for the law’s challengers.

Here’s why: Central to the lawsuit challenging the ID measure is the claim that it violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which bars racial discrimination in voting. In its motion to dismiss the case, Texas argued that Section 2 bars only intentional discrimination, not actions that have a discriminatory effect. In other words, the law’s challengers should have to show that the state consciously set out to make voting harder for blacks or Hispanics—which would be a heavy lift indeed.

That’s not a view that’s won much acceptance from the courts—but it is championed by some prominent conservative legal scholars, who say interpreting Section 2 more broadly risks going beyond what the Constitution allows.

Ramos gave that argument short shrift. “Defendants are incorrect,” she wrote, noting that Congress’s explicit expansion of Section 2 to cover results, not just intent, “has been held to be consistent with the scope of the 15th Amendment.”

And Ramos went on to offer a clear statement of just what the VRA requires that the law’s challengers show: that the law’s disproportionate impact on racial minorities is not just incidental, but is the result of how the ID requirement interacts with past discrimination.

“Plaintiffs have alleged that Hispanic and African-American voters are disproportionately without photo identification and without the resources to easily obtain [state-issued ID cards],” Ramos wrote, rejecting Texas’s claim that the case should be scrapped because the challengers had merely shown an incidental “disparate impact” on minorities. “Plaintiffs have alleged that this disproportionality is related to past intentional discrimination and its lasting socio-economic effects. Thus they do not rely on disparate impact alone.”

That holistic approach was at the heart of the ruling in April that struck down Wisconsin's voter ID law—an opinion that voting-rights groups praised for its nuanced and sophisticated understanding of how discrimination works.

Ramos took a similarly broad view of the Voting Rights Act when she dispatched the state’s claim that the ID law doesn’t encroach on the right to vote because even Texans without an ID can get a state-issued identification card. To support that view, Texas argued that the plaintiffs must show that at least somebody faced an insurmountable burden in voting. Under that interpretation, the law’s challengers would have faced a high bar at trial, even if Ramos allowed the case to go forward.

“Defendants argument is incorrect,” Ramos wrote. “Plaintiffs are required to show a denial or abridgement [Ramos’s emphasis] of the right to vote. Whether the right to vote is completely prevented or partially restricted, the matter is actionable under Section 2.”

Ramos didn’t give the challengers everything they wanted. She sided with Texas in throwing out a challenge to the law under the Texas Constitution, ruling that, under the sovereign immunity doctrine, a federal court has no jurisdiction on the issue. And she said that Dallas and Hidalgo Counties, which had joined the challenge to the ID law, lacked standing to be part of the case.

Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School who has testified before Congress in support of a strong Voting Rights Act, agreed with Tokaji that Ramos’s order doesn’t offer much of a sign about how she’ll ultimately rule. But he put it in the context of the current legal backdrop, in which the Voting Rights Act has been gravely wounded, and conservatives are on offense as they look to further weaken anti-discrimination protections in voting and elsewhere.

“A thoughtful judge applying the law," Levitt said. "In this legal climate, I can get excited about that!"