Climate change isn't a problem; it's many problems. Or rather, it's a "threat multiplier," according to Heather Coleman, Oxfam America's climate change policy manager. What that means is that geopolitical threats like political instability, inequality and disease could become several times more dangerous as the planet gets hotter and the tides rise.

"It's not just environmental harms that it's multiplying in terms of threats, but it's also building off of other threats," Coleman told msnbc.

The latest assessment from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released on Monday, offers a rare, comprehensive survey of those threats. Its findings include a grim picture of subject areas as diverse as future economic growth, gender equality and urban quality of life. Yet some of the report's most dramatic findings concern what is arguably humanity's most basic need. The next few decades of climate change, the IPCC finds, could make a hungry planet significantly hungrier.

"Basically, it's categorical that climate change is going to lead to significant declines in global yields of staple crops," such as maize and rice, said Coleman. She described the latest reports projections regarding hunger and food security as "much worse than what the IPCC had previously estimated."

"All aspects of food security are potentially affected by climate change, including food access, utilization, and price stability," according to the report. In other words, rising temperatures could make food scarcer, more expensive, and harder to safely keep in storage. Some staple crops may even become less nutritious or filling: "Cereals grown in elevated CO2," according to the report, "show a decrease in protein."

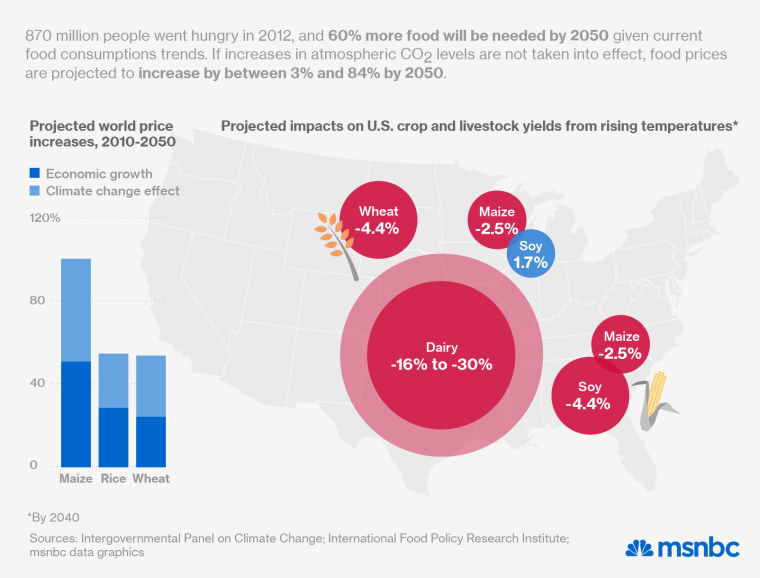

The IPCC report is not prophecy, and its authors acknowledge the difficulty in predicting exactly how climate change will alter something as complex as the global food infrastructure. Even without taking increased atmospheric levels of CO2 into account, the most exact prediction they can make regarding global food prices is that climate change could force an increase of between 3% and 85% by 2050. In some parts of the globe, rising temperatures may even modestly increase crop yields, offsetting in some small way the overall disruption to the global food supply. Yet one thing seems absolutely certain: Global warming's overall effect on hunger will be to make it worse.

Those who are already poor will carry the greatest share of the burden, and not just because they will be unable to keep up with rising food prices.

"Some places are going to benefit from higher temperatures and more rainfall and other places are not, and the gains and the risks are going to be very different from country to country," said FoodTank.org president Danielle Nierenberg. But the regions of the planet which will lose the most in terms of crop yield and food production "are the places in the world that are already most challenged by food insecurity."

The hungriest places on Earth are Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In the former place, "an estimate regional average of 26.8% of the population [is] undernourished," according to the IPCC. South Asia has greater hunger in terms of absolute numbers: 300 million South Asians are undernourished, overall. Both regions are expected to experience water supply problems and lower yields for staple crops.

The week before IPCC's report came out, Oxfam International anticipated it with a report of its own, detailing some of the projected IPCC findings on hunger and proposing various ways to mitigate harm.

"While many countries—both rich and poor—are inadequately prepared for the impact of climate change on food, it is the world's poorest and most food insecure countries that are generally the least prepared for and most susceptible to harmful climate change," according to the report. "No country's food system will be unaffected by worsening climate change."

To limit the damage, Oxfam proposes an ambitious program which includes reducing carbon emissions, "[enshrining] the legal right to food in national law," and funnelling hundreds of billions of dollars into sustainability efforts in poor countries. Agricultural corporations, said Nierenberg, need to change as well.

"The current monoculture systems [where only one crop occupies a vast swath of land] are not resilient to drought and disease and pest," she said. "Smaller, more diversified systems are. Whether the private sector can realize that early on and take a part in it remains to be seen."

Both IPCC and Oxfam also suggest that smaller agricultural producers should be part of the solution. Coleman said that "a mix of agricultural practices" would be needed, but pointed out that "small scale agriculture is less greenhouse gas intensive." The IPCC report emphasizes region-based "indigenous knowledge" as a resource for information on how to adapt to changing environmental surroundings.

But whatever the response to climate change, it is highly unlikely that the global population will be able to avoid serious negative consequences in the short-to-medium term. That's because the threat to food production comes from more than just changing temperatures: Other man-made environmental changes, such as water pollution and soil depletion, are already threatening the world's food supply.

"It's going to be a perfect storm of events for farmers around the world," said Nierenberg. When the storm arrives in earnest, there's no telling what could happen.