For the first time that she can remember, Naquashia LeGrand’s household may go without Thanksgiving dinner. Her family is just too broke, living too close to the margin, to pull off a big turkey dinner, she said.

“Always having Thanksgiving, that’s something my family always made sure we had,” said the New York native. “And just to hear that out of my grandmother’s mouth, it broke me.”

Welcome to the post-hunger cliff holiday season. At the beginning of November, the federal food stamps program was cut by $5 billion, meaning smaller benefit checks for the 47 million Americans who rely on the program. That cut has made this time of year more precarious than ever for millions of households.

Food pantries around the country are reporting a precipitous rise in the number of new visitors as people who were previously able to make do on food stamps get hit with cuts they can’t afford. It will be a long time before the effect of the cuts can be accurately quantified, but the raw numbers currently being reported are suggestive. Previously, many food stamp recipients were able to stretch their benefits until the third week of the month. Since November 1, they have been visting pantries earlier, and in greater numbers.

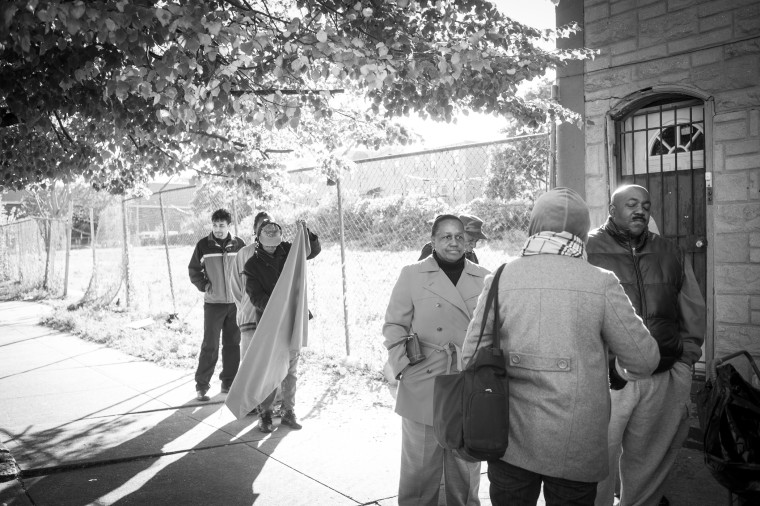

PHOTO ESSAY: One family, trying to keep food on the table

New York City’s largest emergency food pantry, the Brooklyn-based Bed Stuy Campaign Against Hunger, has reported a 35% increase in clients since November 1. The River Fund food pantry in Queens, which opens its doors to the community every Saturday, reported 824 client visits on one Saturday alone.

“Typically we would see between 600 and 700,” visitors, wrote Otto Starzmann, the pantry’s chief production officer, in an email. “So this is a marked uptick. For next Saturday, we’re bracing ourselves for even more people.”

In northern states, expenses generally increase during the winter months as heating bills rise. A 2010 survey [PDF] by the food bank network Feeding America found that nearly half of its clients—46%, to be exact—had at one point been forced to choose between paying for food and paying for utilities. In addition to losing food stamp money, about 300,000 families across the country have seen their home heating assistance get reduced as a result of the across-the-board federal budget cuts known as sequestration.

Many food pantries and soup kitchens offer special Thanksgiving Day programs to help families like the LeGrands. But Joel Berg, executive director of the New York Coalition Against Hunger said those one-day programs do little to ease the crunch through the rest of the season.

“The two days out of the year with the least hunger in America are Thanksgiving and Christmas,” Berg told msnbc. But even on those two days, many food pantries are seeing their resources strained and are facing shortages of Thanksgiving turkey.

“Thanksgiving is always a busy time for us,” said Margarette Purvis, CEO of Food Bank for New York City. “This year it’s a little different. I’m watching soup kitchen and pantry managers make very difficult decisions.”

The Thanksgiving rush is just the latest in a long series of rolling crises for food banks. Before the holiday season, the cooling weather and the hunger cliff, food pantries were already struggling to meet record demand. To make matters worse, olling budget cuts known as the sequester, eliminated a chunk of the government subsidies which help food banks store and distribute their food.

“Food banks have never been here before. This is new territory for us,” said Marianne Smith Vargas, the chief philanthropy officer for the Foodbank of Southeastern Virginia and the Eastern Shore.

Her food bank has been hit hard because a large portion of the residents in the surrounding area are federal employees and federal contractors. When the shutdown occurred in October, many of those on furlough ended up accessing food pantries for the first time. In addition, the shutdown seems to have gouged the food bank’s fundraising efforts.

“We’re behind on fundraising this year as well,” said Vargas. “Probably about $450,000 down from what we raised in the same time frame last year.”

After the winter has passed, around March, the Foodbank of Southeastern Virginia will be better equipped to gauge the effect of the hunger cliff on its community and 400 member pantries. By then, the food stamp program may have already received other harsh cuts at the hands of Congress.

Members of the House and Senate are debating food stamp cuts in a Farm Bill conference committee. The Democrat-controlled Senate has proposed $4 billion in additional cuts to food stamps over the next decade while the Republican majority in the House has passed a bill that would cut nearly ten times that.

Minnesota Rep. Collin Peterson, the top Democrat on the House Agriculture Committee, said Senate Democrats will not accept “double digit”-level food stamp cuts. That leaves open the possibility that $9.9 billion or less could still be excised from the program. Even if that does not happen, $6 billion more in automatic cuts are expected to occur over the next couple of years.

Meanwhile, Washington remains silent.

“As each day goes by and there’s silence from our leaders, it makes you feel not hopeful," said Purvis.