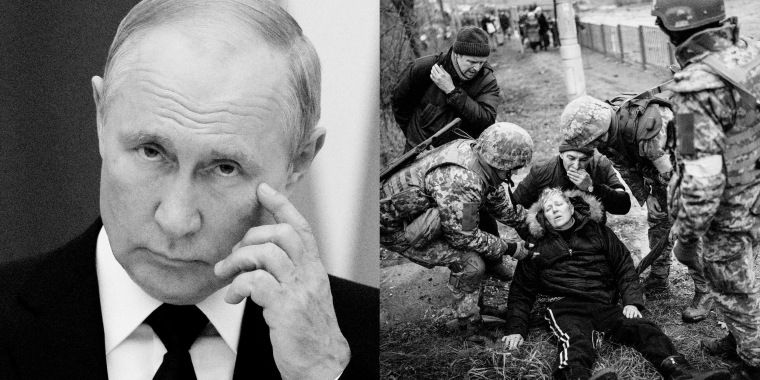

People around the world are calling for Russian President Vladimir Putin to be tried for war crimes over the gruesome fallout from Russia's ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

President Joe Biden on Monday condemned recent images from the once-besieged city of Bucha that appear to show execution-style killings and mass graves. He once again called Putin a “war criminal” but noted that more information will be needed to formally make the case.

Last month, the International Criminal Court prosecutor announced an investigation into potential war crimes committed during the invasion. But Biden's hedge seemed to acknowledge the reality of the situation: Holding top officials accountable for war crimes, let alone Putin, will be difficult.

On Monday’s episode of "The ReidOut," Gregory Gordon, a former war crimes prosecutor and genocide expert, explained the immense burden of proving a war crimes suspect's guilt.

“It is extremely difficult to make these cases,” Gordon said. “You have to have corroborating evidence. You have to have solid witness testimony. You have to have good documentation. And those are the things that I hope the investigators who are being sent [to Ukraine] now are taking care of.”

Prosecutors would need to show that Putin and other top officials were aware of the crimes when they committed them, Gordon explained.

“To show the chain of command and the evidence of communication between and among the people in the chain of command is a very meticulous process that has to be documented with great care,” he said. “If there are any gaps, then prosecutors cannot go into court and establish a case beyond a reasonable doubt. These are very difficult prosecutions to bring and to be successful on. We have to realize that.”

After Joy noted that African leaders have been among those most frequently charged and convicted of war crimes, Gordon attributed the disparity to “realpolitik,” the word used to describe politics focused on practical options — not ethical or moral ones. He said the standards of justice need to be applied more evenly.

“We have to look beyond simply Africa,” he said.

In other words: International courts have managed to convict African officials (and others) for war crimes because they’ve had the means to apprehend these leaders and bring them to trial. Doing that can be harrowing in countries that haven't deposed their rulers, as my colleague Zeeshan Aleem explored in an interview last month.

Putin isn’t just going to leave Russia and willingly head to The Hague to be charged. And as Gordon said Monday, that puts countries opposed to Russia’s war in an unenviable position: hoping for regime change if they want an international court to hold Putin accountable.

“Otherwise," Gordon said, "all his layers of protection and security — his military and everything else — will probably shield him."