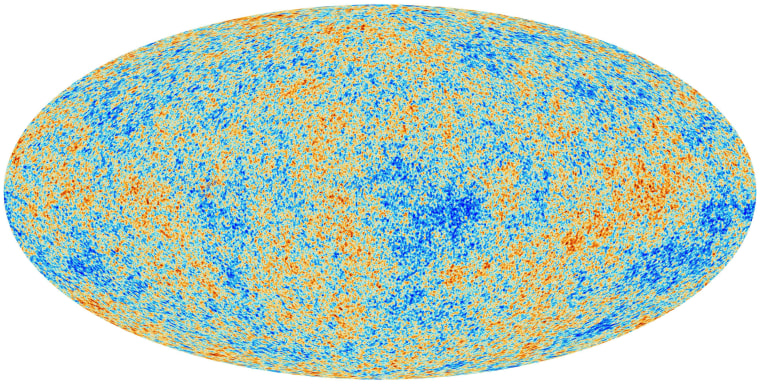

Rachel ended Friday's show with a segment including a picture of the oldest light in the Universe. Since the Week in Geek skipped last week after this picture was released, I thought this would be good opportunity to explain it in detail. As Rachel said, the picture shows our "baby Universe," which in astronomer-speak is when the universe was 370,000 years old. That's a frighteningly old baby by human terms, but an itty bitty one by the Universe's standards.

We actually can't take a picture of the Universe when it was any younger than this because prior to this point, the Universe was so small and dense that photons kept bumping into electrons and weren't able to travel freely until the Universe grew and cooled enough for protons and neutrons to capture these electrons, thereby allowing the photons escape.

Think of it as being like trying to walk through Times Square on New Year's Eve: the place is jam-packed with people, and trying to go in a straight line is next to impossible. But then at midnight, everyone embraces, and suddenly small passages open up everywhere in the spaces between couples and groups of friends. (That's clearly oversimplified, but hopefully you get the idea.)

The photons that were eventually released from our infant Universe have been traveling through space ever since, even as space itself has been expanding, which has caused them to be "redshifted" from infrared radiation to microwaves. Hence the name we have for this image: the Cosmic Microwave Background, or the CMB for short.

This latest image of the CMB was captured by the European Space Agency's Planck satellite. Why do we care about the CMB? Well, in general, because it tells us about the distribution of matter in the early Universe. This allows us to better understand how gravity and expansion acted to produce the galaxies, galaxy clusters, and voids we see today. The color scale in the image illustrates differences in temperature (and therefore matter), with blue being cold, or less dense areas, and red being hot, or more dense areas. The most amazing part is that the difference between the hottest and coldest points on the map is less than one thousandth of a degree.

To learn more, here is a great Q&A on Planck and the CMB and a great write-up of the implications on our current cosmological models.

And now for some geek that's relatively recent:

- New stars in the neighborhood. Astronomers discover a pair of brown dwarfs only 6.5 light years away.

- Data visualization geek: causes of death in the 20th century.

- What the shape of the Neanderthal skull can tell us about the Neanderthal brain.

- The view through a whale's eye. Long, but FASCINATING read.

- Roosters know when to crow, even without exposure to day and night.

- How big is space? Try manually scrolling through it here. It should only take 22 million years or so.

- Abstract "Black Hole" artwork made with power drills and paint.

- Physicists at the University of Chicago have found ways to create knotted vortices, i.e., the most complicated "smoke rings" ever. Watch this video for a great explanation.

- Roadside billboard in Peru uses humidity to produce clean drinking water for local village.

- Jeff Bezos recovers a Saturn V engine from the ocean floor. [WITH VIDEO]

Happy "Geekster"! @Summer_Ash