There are competing explanations as to why radicalized congressional Republicans refuse to compromise, even after failed election cycles, but Nate Silver points to one of the more compelling rationales.

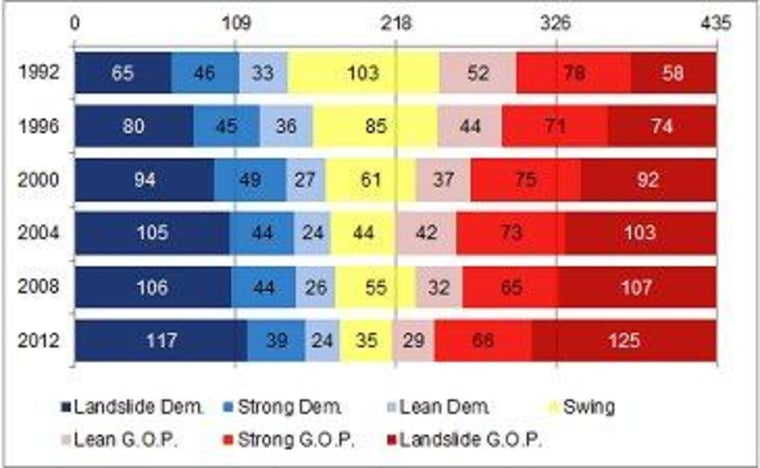

In 1992, there were 103 members of the House of Representatives elected from what might be called swing districts: those in which the margin in the presidential race was within five percentage points of the national result. But based on an analysis of this year's presidential returns, I estimate that there are only 35 such Congressional districts remaining, barely a third of the total 20 years ago.Instead, the number of landslide districts -- those in which the presidential vote margin deviated by at least 20 percentage points from the national result -- has roughly doubled. In 1992, there were 123 such districts (65 of them strongly Democratic and 58 strongly Republican). Today, there are 242 of them (of these, 117 favor Democrats and 125 Republicans).

It creates a dynamic in which GOP lawmakers, even those who might want to play a constructive role in governing, don't feel like they have much of a choice -- if they're reasonable and responsible, they'll face a primary and lose.

Indeed, members have seen this happen plenty of times. My personal favorite Bob Inglis, a conservative House Republican from South Carolina who got crushed in a GOP primary for being insufficiently radical. Inglis expressed a willingness to work with Democrats on energy policy and he said his main focus as a lawmaker was to find "solutions" to problems -- shortly before losing by a ridiculous 42-point margin in a district he'd represented for more than a decade.

The way the lines are drawn, members just don't have much of a choice if they hope to avoid Inglis' fate. As Nate added, "Most members of the House now come from hyperpartisan districts where they face essentially no threat of losing their seat to the other party. Instead, primary challenges, especially for Republicans, may be the more serious risk."

For GOP lawmakers, the way to stay in office is to keep the far-right base happy. And the way to keep the far-right base happy is to avoid compromise and adopt an unyielding stance on every issue.

Nate added, "There have been other periods in American history when polarization was high -- particularly, from about 1880 through 1920. But it is not clear that there have been other periods when individual members of the House had so little to deter them from highly partisan behavior."

The entire American policymaking process has been built around the notion that officials would have to compromise -- committees would have to compromise with one another, which would lead to compromises on the floor, which would lead to compromises with the other chamber, which would lead to compromises with the White House. It's built into the cake -- vote coalitions and deal making are features, not bugs, and there's nothing especially wrong with a system that operates this way.

But when lawmakers lose their incentive to play by the traditional rules, knowing that the best way to stay in office is to toe an aggressive ideological line, the result isn't pretty.

Silver's conclusion, about the practical effects of the situation, and why hyperpartisan districts doesn't really do the GOP any favors, rings true: "The district boundaries that give Republicans such strength in the House may also impede the party's ability to compromise, reducing their ability to appeal to the broader-based coalitions of voters so as to maximize their chances of winning Senate and presidential races. If so, however, that could mean divided government more often than not in the years ahead, with Republicans usually controlling the House while Democrats usually hold the Senate, the presidency, or both. As partisanship continues to increase, a divided government may increasingly mean a dysfunctional one."

Who's up for redistricting reform?