Good things come to those who wait?

The Senate unanimously confirmed Washington lawyer Richard Taranto to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit on Monday, more than 17 months after he was first nominated for the position and more than a year after his confirmation hearing.The nomination of Taranto, a name partner at the D.C. firm Farr & Taranto, never faced much opposition but got caught up in election-year politics last year. The Senate voted 91-0 for the specialist in intellectual property and patent law, who has argued 19 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and taught patent issues at Harvard Law School.

Keep in mind, this vacancy was created by a judicial retirement three years ago. President Obama originally nominated Edward Dumont, who would have been the first openly gay federal appeals court judge, but after Senate Republicans kept waiting for over a year, Dumont couldn't wait anymore and withdrew his name from consideration.

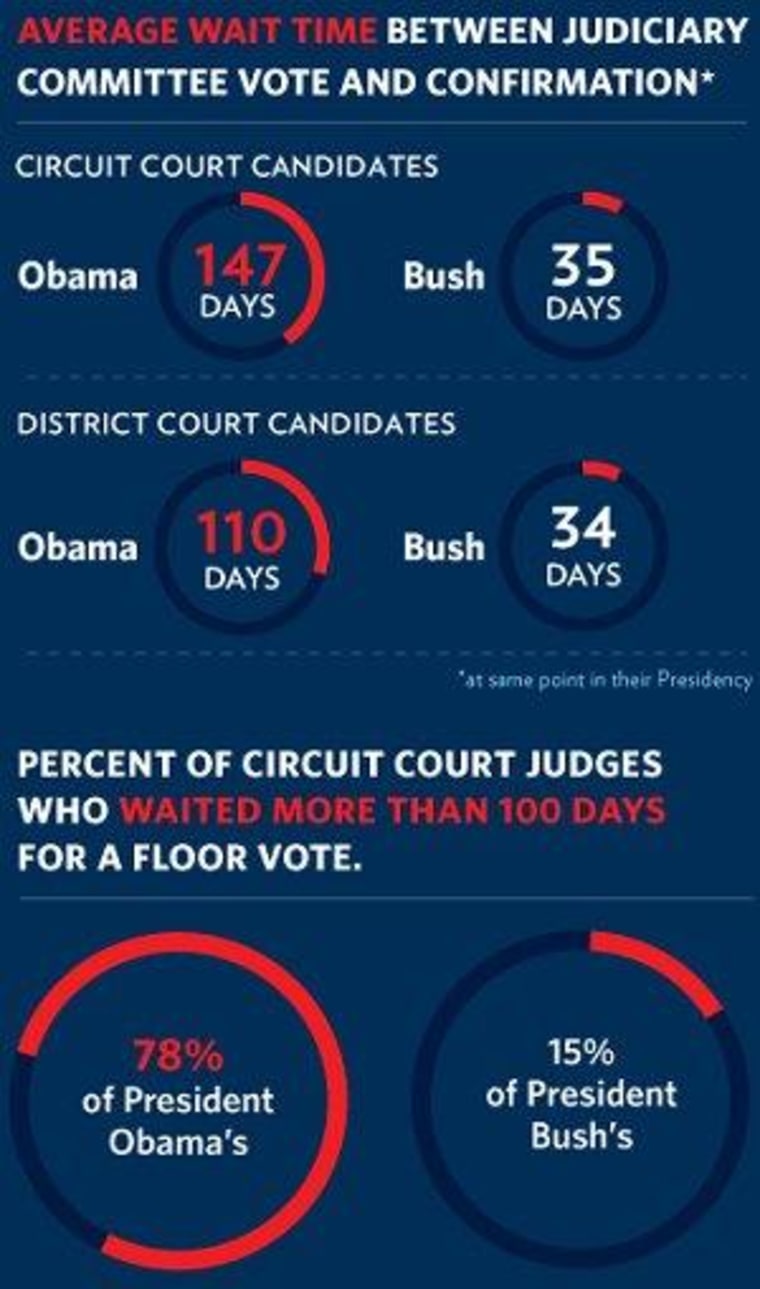

Obama then nominated Taranto. Despite literally no opposition -- he was confirmed, 91 to 0 -- he had to wait literally 484 days from nomination to confirmation.

It's creating an untenable nominating dynamic: judges who enjoy broad support are forced to wait truly ridiculous lengths before receiving a vote, and judges Republicans don't like are forced to wait before failing at the hands of a GOP filibuster.

Perhaps some of you are wonder why this matters. So, some judges aren't getting confirmed? Does it really matter that much?

Yes, actually, it does.

For one thing, this is one of the most important ways in which a president -- not just Obama, but any president -- can leave his or her mark. The judiciary has the capacity to have a major impact on American society, but in order for an administration to help shape those outcomes, it has to have a president's preferred jurists on the federal bench.

We can all think of cases in which court rulings mattered -- on civil rights, campaign finance, the scope of executive power, health care, corporate power, etc. -- and if one party has dominated in shaping the judiciary, that party's ideology will often prevail in close cases.

For another, vacancies matter. Dahlia Lithwick published a gem on this a few years ago, explaining the consequences of a slower, over-burdened court system.

I suppose we can all go on parsing the words "advice and consent" or wish ourselves back to a less partisan era, as ever more seats open up and remain unfilled. But ultimately the judicial-vacancy crisis is a partisan problem with bipartisan consequences. As Nan Aron at the liberal Alliance for Justice puts it, "Every day Americans look to the courts to address problems affecting their daily lives. With the high number of vacancies, their ability to stand up for their rights will be unacceptably delayed."The increasingly partisan confirmation wars also mean that outstanding nominees are unwilling to put their lives on hold for more than a year, and sitting judges are unable to retire. Justice Anthony Kennedy warned in August that the rule of law itself is "imperiled" if we are willing to sacrifice judicial excellence to partisan politics. The unspoken paradox of the judicial-vacancy deadlock is that in regularly denigrating and politicizing the judiciary, we've come to believe that a broken judiciary is not in fact a problem at all.

Looking ahead, White House Press Secretary Jay Carney told reporters yesterday than when President Obama visits with lawmakers on Capitol Hill today "confirming the president's judicial nominations" will be an important topic of conversation.