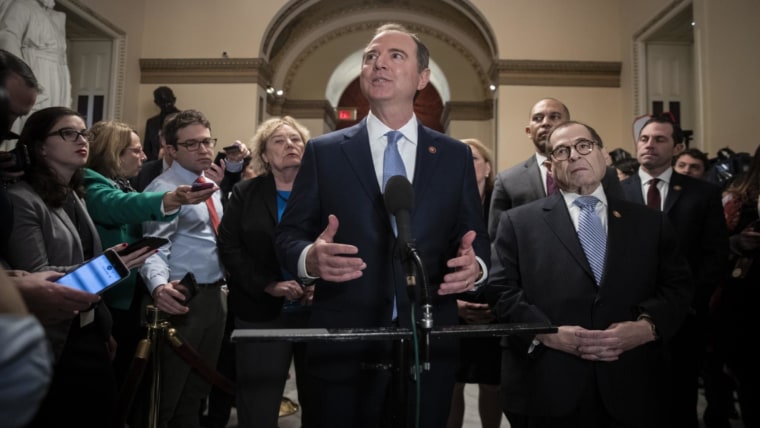

By any objective standard, the House managers' case against Donald Trump in yesterday's impeachment trial was brutal for the president. A New York Times report described House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff's (D-Calif.) case as "meticulous and scathing."

For anyone committed to a good-faith examination of the facts, the second day of the president's trial left little doubt about Trump's guilt. But hanging over the proceedings was an uncomfortable question: if compelling evidence falls in a GOP-led Senate, and Republicans don't want to consider it, does it really make a sound?

The Washington Post's Jennifer Rubin noted that "intentionally ignorant Republicans" in chamber may have been presented yesterday with damaging revelations about their party's president that they hadn't previously heard.

Given how firmly some Republican senators are ensconced in the right-wing news bubble, and how determined they are to avoid hearing facts that undercut their partisan views, it is possible many of them are hearing the facts on which impeachment is based for the first time. Impeachment manager and House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Calif.) took them through in meticulous detail the scheme President Trump devised to pressure Ukraine to help him smear former vice president Joe Biden.

But while GOP senators may have been confronted with a devastating presentation, the California Democrat wasn't in a position to make Republicans care about the case.

Some literally fell asleep in the middle of the day. Some passed notes to maintain conversations forbidden during presentations. The Associated Press noted that senators, "bored and weary" on the trial's second day, eventually started "openly flouting some basic guidelines in a chamber that prizes decorum."

Perhaps the most brazen was Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who was spotted doing a crossword puzzle during the impeachment trial, prompting Dana Milbank to explain, "Paul and some of his Republican colleagues aren't even pretending to treat the proceedings with dignity."

The problem, of course, is that Republicans are simply indifferent to the presentations because they've already decided to excuse the president's abuses. By some counts, as many as 45 GOP senators -- roughly 85% of the Senate Republican conference -- were prepared to dismiss the charges and forgo the trial altogether.

The result is an awkward dynamic in which impeachment managers are winning and losing at the same time: they're presenting a devastating, air-tight case to jurors, many of whom have made little effort to hide their apathy about the underlying scandal.

To the extent that part of their job is to make the case against the accused, the impeachment managers are succeeding beautifully. To the extent that the other part of their job is to sway the jury to remove a corrupt president from office, the managers find themselves in a position in which success is effectively impossible.

The saving grace may be the fact that there's more than one audience to consider. Most Senate Republicans may be struggling to hide their annoyance with having to participate in a trial as if they're unbiased arbiters of guilt, but there are plenty of others -- voters, journalists, scholars, et al. -- who are also watching the proceedings, and while their judgment won't seal Trump's fate in his case, I like to think it's relevant anyway.

Postscript: One of the more common complaints I've heard from GOP senators is that the trial hasn't yet included new information. There's some truth to that. But it's also hard to take their whining seriously: Republicans can vote to subpoena documents and hear witness testimony that would add all kinds of new information to the proceedings. So far, they've refused.