If you read the news these days, there's a good chance you'll see that sociologists believe the United States is on the verge of sustained political violence, that our democracy is on a knife's edge, that voters openly fear a race war and that Facebook is adopting its tools for "at-risk" countries to head off post-election chaos in the U.S. When I get messages from friends asking me whether they should retweet the threat of Election Day violence by a leader of the Oath Keepers militia — after it was broadcast to millions on Alex Jones' radio show — my mind hovers uneasily between two thoughts: The first one is that we are about to have an election in which the threat of violence is real and spreading. I can't remember an election when anything outside of sporadic disorder felt possible.

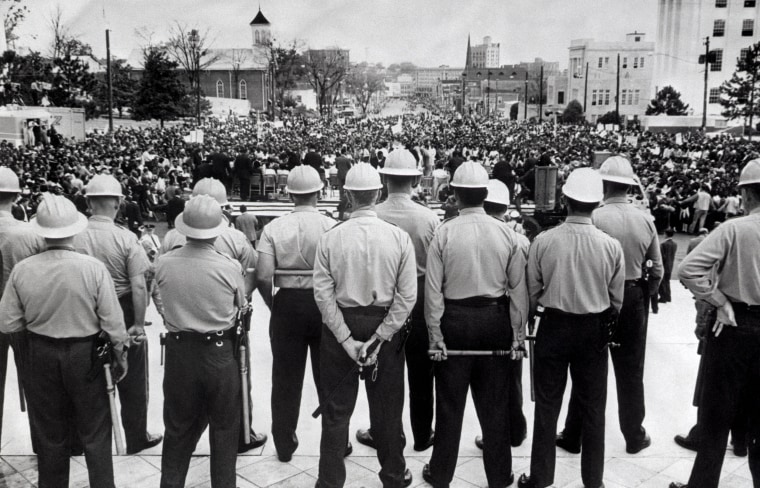

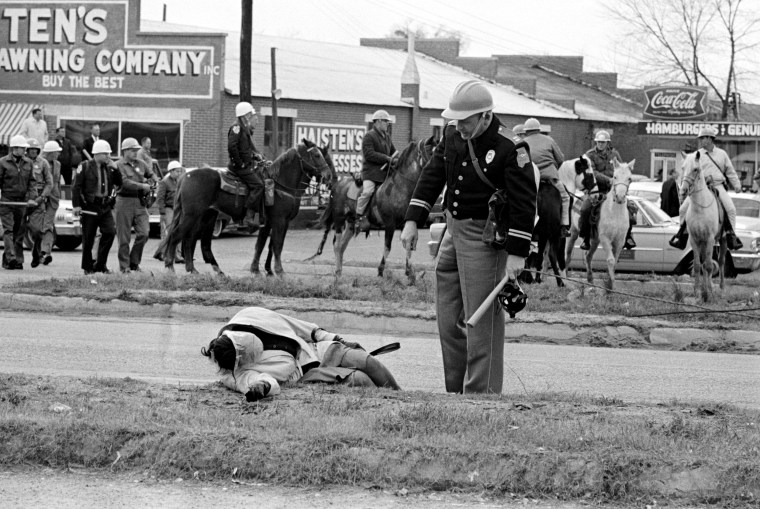

And then sense and history kick in: Political violence, most especially to prevent Black people and other minorities from voting and attaining power, has been a feature of American elections since our country's founding. In the 20th century, white supremacists kindled ethnic resentment and sought to delegitimize a pluralistic democracy. As MSNBC's Chris Hayes has pointed out, referring to the post-World War II Jim Crow South, stationing armed men at polling places was a "key feature of that movement."

One hundred years ago, in 1920, Black residents of Orange County, Florida, spent the summer braving deep, humid swamps to register hundreds of new voters in the county. They conspired with sympathetic white Republicans, who wanted those votes. Black people had been almost completely politically disenfranchised — re-disenfranchised — for decades in central Florida, with the exception of Eatonville, a small town in the center of the county. Orlando was the county seat, and its police chief was a white supremacist, who according to history feared the power of the Black franchise.

On Election Day, when several Black men in Ocoee, a city in the northern part of the county, wouldn't leave polling sites as ordered, a group of white men, helped by the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, tracked them down. Having twice been turned away from the polls, one Black man, Mose Norman, returned to his precinct with a gun. The white gang reportedly used the specter of armed Black men as a pretext. Some historians call the following events a "race riot," but that euphemizes what happened: A throng of white men proceeded to massacre as many as 50 Black people. There is no record of the exact number of people killed, because no one was ever convicted of the killings. When it comes to elections, this massacre and similar events remain open wounds throughout the country.

There is no record of the exact number of people killed, because no one was ever convicted of the killings. When it comes to elections, this massacre and similar events remain open wounds throughout the country.

I grew up around the same area in central Florida, and I had no idea this had happened until I began researching state-sanctioned violence against Black people. It certainly wasn't taught in local schools. (Only as of this year was it included in the public school history curriculum.) There's a new conversation that's been sparked in 2020 about violence — racial violence, and also election violence. Reportedly 3 in 4 voters expect this Election Day to be violent. A key difference is that this year, more white people fear being violently deterred from exercising their constitutional right to vote, and for most white people, they're experiencing this type of fear for the first time. This in itself is a significant fact — that we are talking about election violence more because of who is being affected by it — and it says nearly everything you need to know about racial inequality in America.

Violent domestic extremism has become a leading threat in the country, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Far-right groups have more or less been granted permission by President Donald Trump to incorporate violent imagery and threats in service of their political agendas. When Trump calls out Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer for refusing to open up her state during a pandemic, his audience knows that they can start to shout "lock her up," which, even in the most benign interpretation, means the arrest and detention of a governor for committing no crimes (which, as we know, allegedly really almost happened). In its most extreme interpretation, "lock her up" is an incitement of violence.

When I grew up in Orange County, politics was a joy. My family, led by my mom, instilled in me a love of politics. She was a Tsitizen for Tsongas in 1992, and one day, we hosted a fundraiser to help Paul Tsongas, the quirky, brainy senator from Massachusetts, raise money for his on-again, off-again presidential bid. I was 13, and I decided to wear a badge marked "security," which was primo timing, because the candidate had just lost his Secret Service detail. I loved election days and nights; I once set up a ballot box outside our garage. As a kid, politics was so fun for me.

It took me a while to fall out of love. When I was a reporter in Washington, D.C., the institutionalized b.s. grated on my sense of truth. I had to pretend that there were two equal sides to a story that had at least seven. I had to pretend that, for example, Republican efforts to "prevent voting fraud" had a shred of credibility to them, which is why I wasn't allowed to describe them as "efforts to suppress the Black vote." But what finally did me in was a realization, perhaps too late, that what was great fun for me as a kid was, for so many others, a deadly threat, an unending war for dignity and the basic right to participate politically. And even then I was ignorant of what had happened a few miles north of where I grew up.

In her book "Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice," philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes of the many attempts by so-called enlightened countries to create a civil religion that would bind together its citizens, especially during emergencies. At the core of these efforts were attempts to "expand empathy," she writes, and reduce the influence of human greed and egoism. In our modern life, as we approach an election with extreme trepidation, we might be tempted to ground our appeals to others in respect. I disagree with you, but I respect you; you disagree with me, and yet you respect me. But respect, Nussbaum writes, "is cold and inert, insufficient to overcome the bad tendencies that lead human beings to tyrannize one over the other."

Overt election violence against Black people and Indigenous people and people of color has waned over decades. But the bone-deep sense of dread that many people feel about elections remains.

Overt election violence against Black people and Indigenous people and people of color has waned over decades. But the bone-deep sense of dread that many people feel about elections remains. The reality is that enough white people still see Black political power as a threat to justify extraordinary departures from some of our deepest intuitions about what a mature democracy looks like. Voter suppression is only a more banal descendant of racial violence. To move the conversation forward, we must first acknowledge that a major reason we are at this threshold is that we lack the mechanisms to hold the Republican Party accountable for its efforts to willfully suppress and depress the vote.

My dream is that politics becomes fun for everyone: hard-fought, serious, weighty — but also exuberant and thrilling and inspiring. But based on our current climate, we are far from that reality.