Not since the War of 1812 have armed militants breached the walls of the Capitol. But this time, the insurrection was televised — and hosted on social media websites around the world.

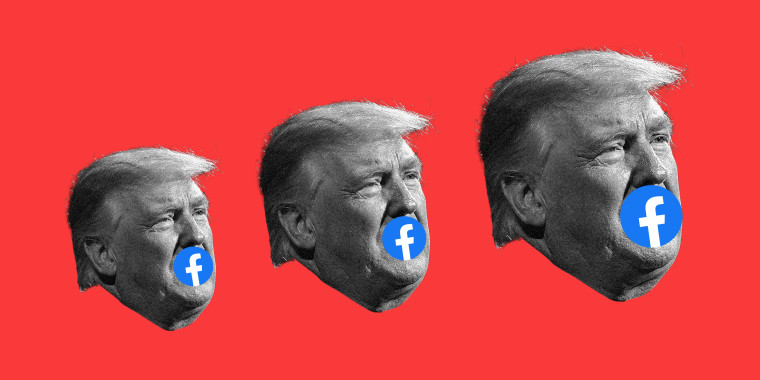

Twitter blocked Trump’s ability to tweet — albeit for less than a day. Facebook suspended his account “indefinitely.”

This is a dark time in American history. Heightened focus on social media, and its ability to fuel extremist actions like violent attacks on the Capitol, show yet again that the next battle for social media regulation will likely be Section 230, the law that provides some legal immunity for internet platforms regarding certain kinds of liability that may arise due to user-generated content. Both President Donald Trump and President-elect Joe Biden have called for repeals of Section 230, and the law has been incredibly controversial for years now.

The recent armed uprising was driven by right-wing extremists and conspiracy theorists (and the immense overlapping population that belong to both camps), many of whom had gathered to promote #StopTheSteal events on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, as well as the no-holds-barred extremist favorite, Parler.

Section 230, broadly speaking, protects websites like Facebook and Parler from being sued for content users post on the sites. For example, if a user posts a defamatory statement on Facebook, the defamed person cannot sue Facebook for that post. This is important because, without this protection, many websites would not be able to operate as they do now, allowing for free and open discussion and exchange of ideas. Small websites in particular would suffer from threats of litigation, and many sites would likely turn to over-censoring their users in an attempt to avoid liability.

While Section 230 can support the ability of websites to provide venues for free speech, it also immunizes websites from legal responsibility for hosting many kinds of harmful content. Due to Section 230 protections, website operators often do not have any legal obligation to take down posts that amount to harassment, doxxing, cyberbullying, nonconsensual pornography, hate speech, disinformation, hoaxes and more. In recent years, we have seen increasingly terrible offline results of online actions, including the wide spread of political disinformation.

Any regulation that targets the online speech of violent extremists seeking to overthrow a democratically elected government also risks targeting the online speech of good faith political dissidents.

In response to the Trump-supporting extremists storming the Capitol, platforms like Twitter and Facebook have finally taken the previously unprecedented leap to ban or block Trump’s account. Twitter blocked Trump’s ability to tweet — first for less than a day, before permanently suspending his account "due to the risk of further incitement of violence." Facebook suspended his account “indefinitely.” Twitch also banned his account. Even e-commerce platform Shopify joined in, deleting all Trump merchandise from its website.

Some may say tech platforms didn’t act fast enough and could have done more. But whether we wanted a faster response or not, it is still a positive sign that platforms have increased their moderation efforts — and better that it’s happened in a thoughtful and careful manner, over the course of the past few years. And it’s a good thing that we were able to see what was happening unfolding live as it happened, from multiple sources (including streamed and posted from the insurrectionists themselves).

In the aftermath of the attempted coup, it is easy to claim platforms should have known immediately to take down posts that are obviously harmful — like Trump’s message of support and encouragement (“We love you, you are very special”) to his violent, armed insurrectionist supporters waving the Trump campaign flag while storming the Capitol with guns and zip ties. But it is harder to create blanket rules in advance on what kinds of content should be kept up or taken down.

Content moderation is particularly difficult because there are many values at play. One reason why many platforms did not take strong actions to moderate Trump’s posts until relatively recently was that he was and still is the president of the United States. There is a clear newsworthy interest in allowing the public to access the opinions (no matter how ridiculous or incorrect) of the leader of one of the most powerful nations in the world.

Content moderation is particularly difficult because there are so many values at play.

Platforms have had to balance this newsworthy public interest with the potential harm caused by Trump’s posts. The scales have been tipping more and more recently. A combination of Trump’s increasing irrelevance and the increasing harm are what ultimately spurred platforms to finally shut him down (albeit temporarily for some).

While it is true that disinformation and extremism are critical problems to tackle on online platforms, it is imperative that we approach future regulation carefully. We do not want extremism to proliferate freely on social media websites, radicalizing vulnerable people and potentially infecting all of society, with often violent results. But we also don’t want an internet where people are not able to express themselves. In many places around the world, the internet is the last place where political dissidents can gather and voice their opinions.

The problem is that any regulation that targets the online speech of violent extremists seeking to overthrow a democratically elected government also risks targeting the online speech of good faith political dissidents trying to fight back against tyranny. We must work to guard against the harms of disinformation and extremism while still protecting free speech and the ability of the internet to connect the world.

Trump himself has not been a fan of social media platforms, despite being an incredibly prolific user, of Twitter in particular. The president has called repeatedly for a repeal of Section 230 and has accused platforms of bias against conservatives and against himself.

He has gone so far as to sign an executive order on social media calling for the Federal Communications Commission to engage in rule-making on Section 230; attempt to tie a Section 230 repeal into a coronavirus stimulus bill; and, most recently, veto a critical National Defense Authorization Act because Section 230 was not revoked. Biden has also not been a fan of Section 230 and has made numerous confusing comments about his desire to see the law repealed.

Trump himself has not been a fan of social media platforms, despite being an incredibly prolific user, of Twitter in particular.

It doesn’t take a fortune teller to predict that political pressure will soon force a repeal or drastic modification of Section 230. However, if and when that happens, policymakers must remember that repealing Section 230 won’t necessarily prevent catastrophes like what we saw happen at the Capitol. What will happen, however, will be a net loss in the ability of the internet to allow all of us to speak and express ourselves freely.

It is 2021. The Trump presidency is almost over, despite the fact that the president still refuses to admit it. The Biden administration and the new Democratic majority in the House and Senate will likely determine the fate of Section 230 and the thrust of internet regulation moving forward. Hopefully, any new legislative or regulatory action will take into account both the harms and the benefits of a free and open internet. In the meantime, all of us can only do our best to be good netizens, avoiding disinformation and doing our part to better the internet — while we still have it.