On Monday, the Trump administration released the first, and only, report from the President's Advisory 1776 Commission. Its authors insist that the 45-page document is an effort to set the historical record straight. "In order to build up a healthy, united citizenry," they write, "scholars, students, and all Americans must reject false and fashionable ideologies that obscure facts, ignore historical context, and tell America's story solely as one of oppression and victimhood rather than one of imperfection but also unprecedented achievement toward freedom, happiness, and fairness for all."

Oddly enough, for a report that claims to offer the clear facts of American history, there are no scholars of American history among its authors.

Oddly enough, for a report that claims to offer the clear facts of American history, no scholars of American history are among its authors. To be sure, academics and experts from other fields and Americans from all walks of life can weigh in on the shared history of their nation. But the complete lack of involvement from those who were trained in the field and who teach it today means the 1776 report winds up doing exactly what it claims others do: obscuring facts and ignoring historical context.

Since its release, historians have denounced the report in no uncertain terms, drawing attention to its shoddy scholarship while decrying its clumsy partisan intent. The "1776" project as a whole was a thinly veiled response to The New York Times Magazine's "1619 Project" — for which I wrote an essay on the impact of racism on urban planning.

That backdrop, and the report's release on the federal holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr., means that the report's distortions of the civil rights movement deserve special attention.

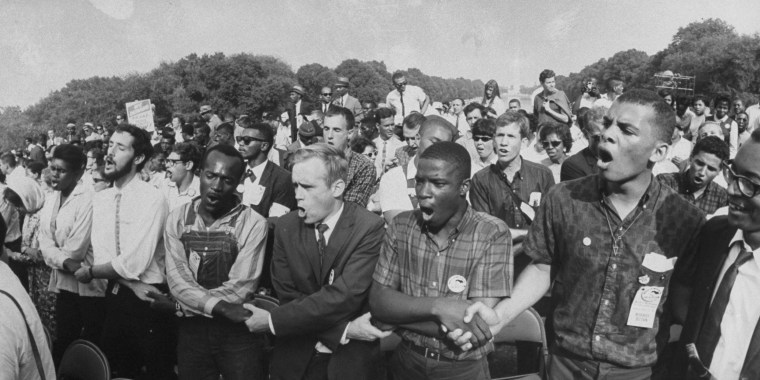

According to the authors, the modern struggle for Black equality can be easily split into two separate and unequal stages. First, they say, there was the civil rights movement, which is pointedly presented here not as a revolutionary cause championed by African Americans in the South but rather "a national movement composed of people from different races, ethnicities, nationalities and religions" — effectively a precedent of the "All Lives Matter" rhetoric of our own time.

"The civil rights movement culminated in the 1960s, with the passage of three major legislative reforms affecting segregation, voting, and housing rights," the report notes, reassuring readers that during this period the movement "presented itself, and was understood by the American people, as consistent with the principles of the founding."

The report’s distortions of the civil rights movement deserve special attention.

But, of course, the civil rights movement and the landmark legislation it prompted were deeply controversial at the time. Countless Americans opposed these laws and, pointedly, claimed that it was their resistance that reflected the "principles of the founding."

When Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina filibustered the Civil Rights Act of 1957, for instance, he pointedly recited the entire Declaration of Independence to link his act of defiance to the colonists' acts. When Gov. George Wallace of Alabama denounced the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 at a segregationist rally, he, too, claimed that segregationists were like the "stalwart patriots" of the American Revolution.

The 1776 report ignores this resistance to the civil rights movement, in which segregationists made their own claims to "the principles of the founding," to present a simplistic view of a controversial campaign that was routinely resisted through acts of police brutality, vigilante violence and even bombings and assassinations.

This sanitized version of the struggle for Black equality serves a purpose, of course, as it lets the authors draw a stark contrast between the "good" struggle of the 1960s and modern demands for equality. "The civil rights movement was almost immediately turned to programs that ran counter to the lofty ideals of the founders," the report argues, presenting affirmative action programs as "distortions" of the nation's true principles.

It’s not surprising that the authors of the report cling to the only line of King’s that many conservatives apparently know.

The 1776 report argues not merely that affirmative action was a departure from the values of the founders, but that it was, in their view, a departure from the values of the civil rights movement. "Identity politics," the report asserts, "is the opposite of King's hope that his children would 'live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,' and denies that all are endowed with the unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

It's not surprising that the authors cling to the only line of King's that many conservatives apparently know, while the rest of us can read King's extensive comments to see that this claim is utter nonsense.

In his 1964 manifesto, "Why We Can't Wait," King asserted that the nation owed a special debt to African Americans: "Few people consider the fact that, in addition to being enslaved for two centuries, the Negro was, during all those years, robbed of the wages of his toil." As a result, he concluded, African Americans deserved "a massive program by the government of special, compensatory measures which could be regarded as a settlement."

Likewise, in his 1967 book, "Where Do We Go From Here?" King again made the case for affirmative action clearly, directly rejecting the argument that the 1776 report uncomfortably assigns to him. "The Negro must have 'his due,'" he argued. "It is, however, important to understand that giving a man his due may often mean giving him special treatment."

King acknowledged that his assertion would be "troublesome" for many, "since it conflicts with their traditional ideal of equal opportunity and equal treatment of people according to their individual merits."

"But this is a day which demands new thinking and the reevaluation of old concepts," he wrote. "A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds or years must now do something special for him, in order to equip him to compete on a just and equal basis."

Despite King's vocal advocacy for affirmative action, the 1776 report bizarrely holds him up as the antithesis of those programs and "identity politics" writ large. Not content simply to erase this aspect of King from the historical record, the authors go several giant steps further by suggesting that affirmative action programs had a conception of "'group rights' not unlike those advanced by Calhoun and his followers," referring to John C. Calhoun.

Drawing a straight line from the South Carolina politician Calhoun, one of the most infamous defenders of Black enslavement, to the African Americans who advocated affirmative action as a remedy for that very enslavement is, to say the least, an incredible stretch.

To be sure, Calhoun's political claims were revived during the civil rights era — by segregationists. As much as Calhoun proposed that slave states could use his doctrine of "nullification" to reject any federal law against slavery, his ideological heirs argued that segregated states could use a similar doctrine of "interposition" to reject any federal order against segregation.

Indeed, all sides of the civil rights struggle understood this obvious fact. "The difference between nullification and interposition is naught," The Montgomery, Alabama, Advertiser asserted in 1956, approvingly linking Southern segregationists and Calhoun. King agreed; in another line from his "I Have a Dream" speech, he pointedly denounced Wallace with "his lips dripping with the words of 'interposition' and 'nullification.'"

To recap: The 1776 report presents Calhoun, the inspiration for segregationists, as a forefather of "identity politics," while King, a strong supporter of affirmative action, is positioned as an opponent.

The 1776 Commission's report is riddled with these ridiculous errors, but I should note that there is one claim that historians would strongly support. "States and school districts," the authors write, "should reject any curriculum that promotes one-sided partisan opinions, activist propaganda, or factional ideologies that demean America's heritage."

That's precisely what the 1776 report is. And why all Americans should reject it.