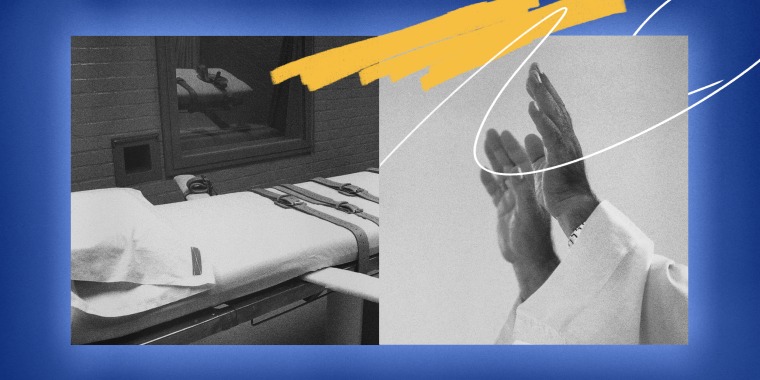

John Ramirez is going to die soon. Texas will put him to death for the 2004 killing of 46-year-old convenience store clerk Pablo Castro. The United States Supreme Court will tell us exactly what can happen in the execution chamber as he dies.

The Supreme Court has never decided what, if anything, a spiritual adviser can do inside the death chamber.

Ramirez wants his spiritual adviser, a Baptist pastor he met while in prison, to be able to touch him and audibly pray while he is being put to death by lethal injection. Texas says the pastor can be in the death chamber but cannot put his hands on Ramirez or pray out loud.

If this conservative Supreme Court is as protective of religious rights as it appears to be, then it will protect the rights of Ramirez, a death row inmate, just as it protected the rights of employers that wish to deny their employees contraception, religious schools that wish to discriminate against their employees, religious adoption agencies that do not want to work with same-sex couples and people who object to Covid-19 restrictions on religious grounds.

The Supreme Court has never decided what, if anything, a spiritual adviser can do once inside the death chamber. Previous cases have only addressed whether death row inmates have the right to have their spiritual advisers present. And previous cases have answered this question inconsistently. In 2019, the Supreme Court allowed Alabama to execute a Muslim man without his imam present in the death chamber but then a month later stopped Texas from executing a Buddhist man without his Buddhist priest present. Part of the difference in treatment, according to some members of the court, is that the Muslim man waited too long to ask for his imam to be present. This year, the court prohibited Alabama from executing a death row inmate without his pastor present.

On Tuesday the court heard arguments on whether Ramirez possesses a constitutional or statutory right to have his pastor not only present, but to physically touch him and pray out loud. The First Amendment’s free exercise clause is designed to protect an individual’s religious liberty and prevents the government from restraining an individual’s free exercise of her religion, with lots of caveats and exceptions. And the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act specifically protects the religious rights of prisoners.

If Ramirez can show that Texas’ decision to bar his pastor from touching him and praying out loud substantially burdens his exercise of his religion under the First Amendment’s free exercise clause rights or under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, then Texas must show it has a compelling state interest for that substantial burden and that there is essentially no other way to achieve that interest.

Texas says Ramirez’s request violates its security procedures and that Ramirez didn’t follow proper procedures and should have asked for his pastor to be present before he filed his suit. And to the substance of Ramirez’s claims, Texas argues it is not substantially burdening his religious rights. Instead, it simply decided not to grant all of his requests, which he claims are a necessary part of his religion.

Ramirez’s argument brings a clash of considerations the court tends to defer to.

Ramirez’s argument brings a clash of considerations the court tends to defer to. This is a court that has been very protective of religious rights. (See the court’s recent decisions in cases addressing religious objections to Covid-related restrictions.) This is also a court that appears deferential to the government’s need to maintain the security of its prisons.

Oral arguments evidenced a sharp fault line in the Supreme Court. The conservative wing of the court worried that granting Ramirez’s request would open the floodgates to other death row inmates asking for other religious accommodations and wondered whether Ramirez’s religious beliefs were sincerely held. Chief Justice John Roberts, for instance, asked what would happen if Ramirez’s religious beliefs dictated that three people be in the execution chamber with him. The liberal wing of the court was far less worried about opening the floodgates of litigation by ruling in favor of Ramirez. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, perhaps the most liberal member of the court, argued that under current federal law, Ramirez is legally entitled to having the prison work in good faith to accommodate his religious beliefs.

There is something jarring about hearing conservative justices wringing their hands over whether and how to accommodate a death row inmate's religious beliefs when they have been far more concerned about protecting an individual’s religious beliefs in situations that could pose far greater harm to others. Let’s again remember the employers who can opt out of providing their employees with contraception, the schools that can discriminate against their teachers, the places of worship that do not have to adhere to health and safety regulations, the religious adoption agency that does not have to work with a same-sex couple.

If the court rules against Ramirez, then it should be clear on exactly why Ramirez’s religious beliefs cannot be accommodated. Otherwise, the court will be leaving itself open to the criticism that it inconsistently applies legal doctrine in order to hand wins to favored people and groups.