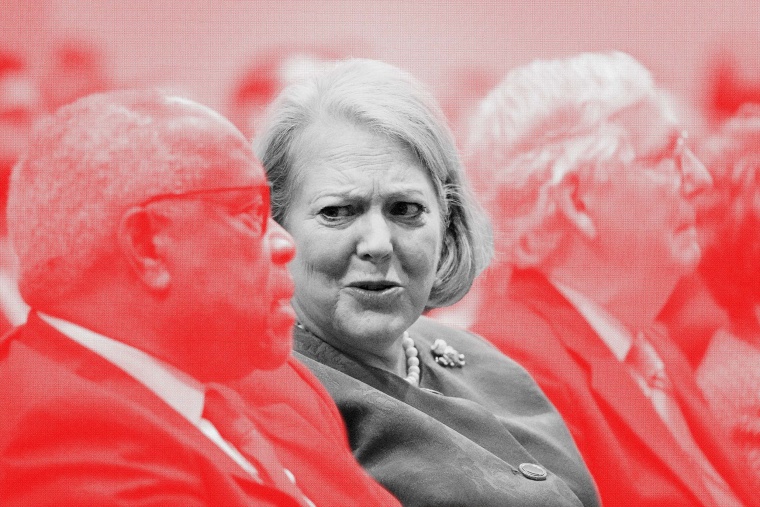

New reports indicate that Ginni Thomas, who’s married to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, was even more involved than we knew in systematic efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s 2020 victory over Donald Trump. We knew that she had sent a barrage of texts to Trump’s White House chief of staff Mark Meadows in an effort to overturn the 2020 election. We knew she’d reportedly emailed the aide of a prominent conservative in the U.S. House of Representatives and said his group needed to be “out in the streets.”

Ginni Thomas was even more involved than we knew in efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s 2020 victory.

We knew that she’d reportedly sent emails to John Eastman, one of Trump’s attorneys, who provided a roadmap for the fake electors scheme. We knew she’d attended the rally that occurred right before the riot on Jan. 6, 2021. According to past reports, she emailed 29 Republican lawmakers in Arizona urging them to contest Biden’s win there. The latest development is that she also contacted Wisconsin lawmakers in an effort to overturn the election.

Even so, we should be careful not to make systemic changes to the Supreme Court because of what Ginni Thomas did while married to Justice Clarence Thomas.

Let’s be clear, for the reasons listed above, Justice Clarence Thomas should have recused himself from weighing in on at least some of the litigation related to the 2020 presidential election. His spouse, Ginni Thomas, didn’t just vocally support one candidate. She lobbied for people across the country to help to overturn her candidate’s loss.

The Supreme Court weighed in on whether the House Select Committee to Investigate Jan. 6 could obtain certain records held by the National Archives and Records Administration. Only one of the nine Supreme Court justices said the committee should not be able to obtain those documents. You guessed it: Justice Thomas.

Thomas should have recused himself, but he was not required to do so. There is a judicial code of conduct for federal judges that applies to every federal judge in the country except nine. You guessed it again: the Supremes. But here is a misunderstood point. Even for all of the lower court judges who are subject to the code of conduct, the code itself is an “aspirational set of rules” and not binding law. There is no enforcement mechanism. And it is only in very rare circumstances, that a judge who violates the code of conduct will face judicial discipline, such as being prohibited from hearing new cases.

In addition to the code of conduct, there is also a federal disqualification statute (the code of conduct references, nearly verbatim, the disqualification statute). Disqualification questions are appealable to the highest court in the land, that is, the Supreme Court. There is no one else to appeal to once you’ve reached that court.

The current statute requires judges, including Supreme Court justices, to recuse themselves when their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” That is a distressingly broad standard. It is so malleable it might as well be made of liquid. But even so, when your spouse is involved in plotting to overturn an election, and you’re ruling on cases dealing with a mob that storms the Capitol to try to overturn the election, it is fair to say your impartiality might reasonably be questioned. However, one person’s bad behavior, or, in this case, one power couple’s ethically questionable behavior, should not necessarily lead to a systemwide change.

While this may be an unpopular view, there are good reasons not to have a mandatory code of ethics that applies to the Supreme Court. The idea raises certain concerns over separation of powers in our system of co-equal branches. A mandatory judicial code of conduct could amount to the legislative branch improperly taking power from the judicial branch. In addition, the code itself would be subject to judicial review by the Supreme Court. Among other issues, there is also the question of who would enforce a code of conduct that applies to that court. Would it be other members of the Supreme Court? Some uber supreme court that oversees the actual Supreme Court? That would be unconstitutional.

There are reasons we should tread carefully when we are talking about imputing one spouse’s activities or views to the other spouse.

In addition, there are reasons why we should tread carefully when we are talking about imputing one spouse’s activities or views to the other spouse. Spouses often disagree on big issues. Sure, not every couple will look like the famous pairing of Democratic strategist James Carville and Republican strategist Mary Matalin. But neither is every couple in lockstep on their political, legal or social views. Let’s consider some additional examples: a criminal defense attorney and a prosecutor, an astrologer and a physicist, a coal company executive and an environmental activist, or Elon Musk and, well, anyone. And even when couples are in general philosophical agreement, that doesn’t mean they fail to exercise independence in their professions.

Most cases will not be as stark as the case of a conservative activist trying to overturn a presidential election and her conservative Supreme Court justice husband ruling on an investigation into rioters who sought to overturn that presidential election. The solution is to nominate and confirm judges and justices who seek to do everything possible to ensure that their impartiality is never questioned. When that doesn’t work, the solution may be political and peer pressure. Additional codes of conduct are unlikely to do much more than make us all feel like we did something to strengthen the integrity of the judicial branch, while actually not doing much at all.