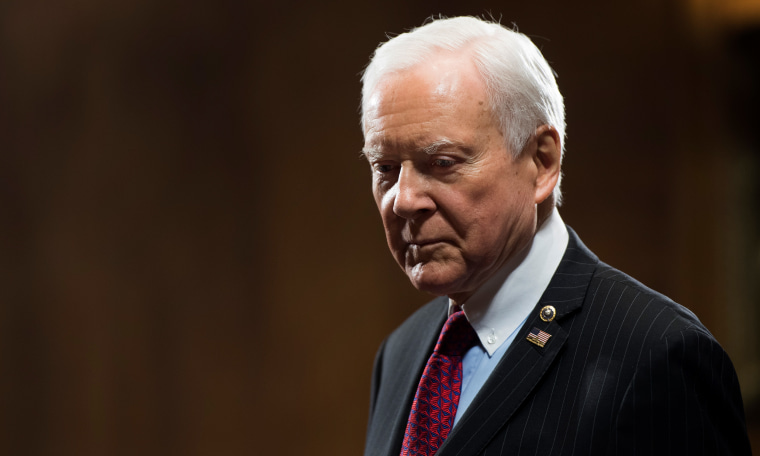

My 2015 piece about being an autistic journalist covering Washington included an anecdote about an interaction I had with Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah and my deep embarrassment from my violation of Senate decorum. My stomach dropped when I got an email saying Hatch, then the chair of the Senate Finance Committee and the most senior Republican senator, wanted to talk to me.

Hatch’s telling me his sponsorship of the Americans with Disabilities Act was his proudest moment in the Senate was a reminder that most politicians want to get policy right.

My fears were unfounded. Hatch’s telling me that his sponsorship of the Americans with Disabilities Act was his proudest moment in the Senate was a reminder that most politicians want to get policy right, even if they don’t succeed.

When Hatch died Saturday at age 88, and I couldn’t help but be sad. But I also mourned the reality that he so often chose the more partisan route, even when it meant tarnishing the ADA, the crown jewel of his legacy.

It might come as a surprise to some, but before the signing of the ADA in 1990, there was a tradition of conservative Republicans’ supporting disability rights. Their positions made sense inasmuch as the promotion of disability rights was seen as helping people with disabilities be fully integrated into their communities and hopefully find gainful employment and independence.

Disability rights activist Evan Kemp was conservative enough for President George H.W. Bush to appoint him to as chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission when Clarence Thomas was appointed to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Kemp was also friends with Thomas and his wife, Ginni Thomas.

Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, who was appointed by Bush, had been a Republican governor of Pennsylvania. Thornburgh’s son Peter was left with a brain injury after a car crash, and the elder Thornburgh helped sell the ADA to Congress as a means of empowering and liberating people. Justin Dart, the cowboy hat-wearing disability rights activist who sat beside Bush as the president signed the ADA into law, said he quit the Democratic Party because “I gradually came to appreciate the importance of independence and liberation from too much paternalistic central government.” (Dart would later become disillusioned with the GOP and supported Bill Clinton in 1996.)

Hatch, a Latter-day Saint, came to care about disability because his brother-in-law had polio and slept in an iron lung. “I personally carried him in my arms all the way through the Los Angeles Temple of my faith,” Hatch said at the time.

His co-authorship of the ADA didn’t make Hatch a liberal by any stretch. He had a history of making noxious comments about gay people, including saying he’d oppose gay teachers just like he’d oppose Nazi teachers and characterizing Democrats as “the party of homosexuals.”

His co-authorship of the ADA didn’t make Hatch a liberal by any stretch.

Nevertheless, when Jesse Helms, the Republican senator from North Carolina, tried to include an amendment in the ADA to allow restaurants to keep workers with AIDS from handling food, Hatch neutered it with the requirement that the secretary of health and human services create a list of diseases that could be spread through the handling of food.

“I think if we would rely more on science and a little less on fears and misperception we would be better off as a society, as a nation, and there would be less prejudice,” Hatch said.

Unfortunately, Hatch was also more than willing to go along with the GOP’s willingness to erode disability rights, which kicked off in earnest after the passage of the ADA. In 2012, three years before our call, Hatch joined other Republicans who had voted for the ADA to oppose the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a U.N. treaty that would have promoted the rights of people with disabilities. Hatch wouldn’t give even after a friend, former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, himself disabled, personally lobbied Republicans on the Senate floor.

During one of the Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, disability rights activists chanted "No cuts to Medicaid! Save our liberty!" and Hatch responded, “If you want a hearing, you better shut up.” In 2020, by then retired from the Senate, he wrote an op-ed criticizing “drive-by lawsuits” that resulted from the ADA and called for weakening the very law he helped author by giving businesses a grace period to correct inaccessibility. Never mind that the law is as old as I am and that businesses have had just as long to comply with it.

I should have known he would take these positions, but I guess I expected more having experienced his personal decency myself. I had experienced him as a gentleman with a first-rate mind making witty ripostes in Capitol hallways.

But being personally kind doesn’t mean one doesn’t also make glaring errors. In ignoring the counsel of his friend Dole, in shouting down those protesters, in supporting weakening the ADA and in writing an opinion piece that called for it to be gutted, Hatch made such errors.

Which breaks my heart. Because whatever commitment he had to making good policy gave way to his commitment to a Republican Party that’s grown less and less committed to the ADA.