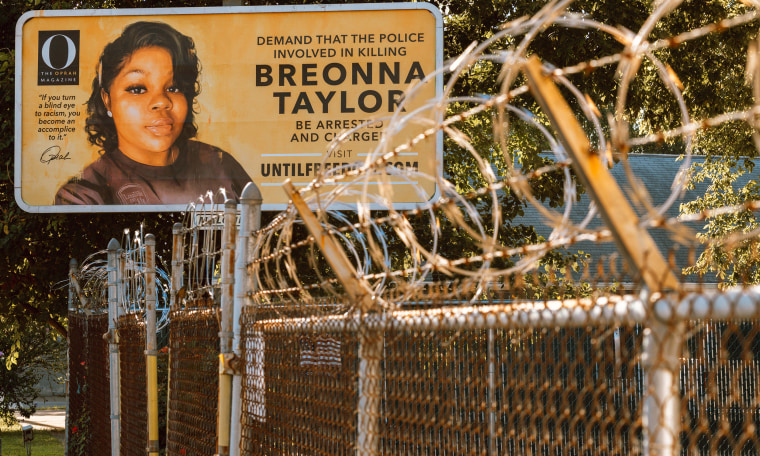

UPDATE (Aug. 4, 2022, 11:35 a.m.): On Thursday, DOJ charged four current or former Louisville police officers with civil rights violations believed to have contributed to the death of Breonna Taylor in 2020.

There is not a day that goes by that I do not think of Breonna Taylor. It took months for news of her killing at the hands of the Louisville Police Department to reach the national media. On the same day I spoke, and cried, about her death on my former podcast, “Pod Save The People,” Errin Haines, editor-at-large for The 19th, reported on the story in a collaboration with The Washington Post. (The 19th is a nonprofit newsroom covering gender, politics and policy.)

If Black women are good enough to carry this country on its back, winning its elections and securing its democracy, we should be worthy of its protection.

A few months later, when the grand jury in her case returned with an indictment for only one officer — and for the wanton endangerment not of Taylor, but of her neighbors — Haines reached back for a quote, as she had done many times since we first met in Ferguson, Missouri, to discuss yet another moment of Black pain.

“This is the lowest charge in one of the highest profile cases. What are folks supposed to tell their daughters?” she texted.

“The truth,” I said. “That they love our labor and not our lives.”

Such is the cycle for Black people, especially Black women, in America. We continue to be, as author Zora Neale Hurston proclaimed, “the mules of the world.” Taylor labored as an essential worker, an EMT on the front lines of a deadly pandemic and was still discarded by officers who cared nothing for her life and a system that treats us as disposable.

If Black women are good enough to carry this country on its back, winning its elections and securing its democracy, we should be worthy of its protection. And our protection is rendered impossible without fully examining and altering the systems that do us harm, from the medical apartheid that killed Dr. Susan Moore to the law enforcement systems that killed Breonna Taylor.

It should concern every American — not just the Black ones — that our tax dollars pay into a system that kills over 1,000 people annually.

Those same systems left Jacob Blake paralyzed from the waist down after officers shot him in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Yet there will be no accountability for the police officers involved. Just today, we learned that Kenosha police officers who shot Blake seven times as he walked away from them will not face charges.

The news reflects yet another unjust outcome for Black lives, and should tell you all you need to know: The issue of police shooting unarmed Black people is not about bad apples or bad actors, it’s about a bad system.

Now is the moment you may be tempted to delve into the specific elements surrounding Taylor's death, Blake’s life-altering injuries, and so many other tragedies. These events often compel us to magnify each factor and detail. Conversations about deadly police encounters often tread quickly into the details. Countless articles, television segments and Twitter threads are dedicated to the painstaking detailing of these events, from departmental procedure to officer history and the timeline of the incident.

Often, these details quickly veer into victim blaming — the idea that Taylor, Tony McDade, Rayshard Brooks and many others did something to cause their own deaths, or Blake to incur his own paralysis. Look no further than the responses to my most recent segment on MSNBC’s “American Voices” discussing Breonna’s life: Accusers with misinformed details on the case insist that she caused her own demise. Blackness is treated as a weapon unto itself worthy of a death sentence, as presumptions of innocence are applied to blue and not Black. And justice — let alone accountability — rarely materializes.

The same has been true in the latest developments in the investigation of Taylor’s death. Louisville’s interim police chief now intends to fire two more officers involved in the killing, and The New York Times recently released a digital re-enactment of the scene of her death. Certainly, Taylor’s family deserve an answer to every question they may have about what happened that night.

But Taylor’s death is not an aberration in policing. It is the norm. These obsessive procedural conversations excuse us from critically interrogating the institution that allows such injustices to persist. In truth, Taylor’s death was not merely the result of policy violations or tactical errors. It is the repeated and consistent result of an institution that fails to protect and serve as promised.

Nearly 80 percent of survivors who had not previously called police would still not do so in the future.

Even a cursory examination of the institution of policing immediately clarifies that something is amiss. We are told that police departments, and the criminal legal systems within which they operate, serve essential functions of public safety: to prevent, solve and deter crime.

We should all be able to sleep soundly knowing that “protect and serve” isn’t merely a slogan, but a way of life. Instead, it’s a lie.

Are the police preventing crime? Recent revelations about the Nashville bomber give a worrisome answer amid reports that law enforcement had received several warnings about Anthony Quinn Warner’s intentions to commit crimes of domestic terrorism, yet failed to act on them until it was too late.

Domestic abuse survivors are less likely to call police to protect them, due to the perceived and real fear about policing failures: Nearly 80 percent of survivors who had not previously called police would still not do so in the future, and 1 in 4 women report police officers arresting them instead of their abusers. The idea that more police can prevent more crime lacks substantial evidence, as major U.S. cities have experienced a decline in violent crime even while the numbers of officers on the force have gone down.

Are the police solving crime? Certainly not to the levels that consistent budget increases would indicate. Only 46 percent of violent crimes are cleared by law enforcement. That number plummets to 18 percent for property crimes, which constitute the vast majority of criminal incidents. Should any civilian employee like you or I achieve an annual 18 percent success rate, we’d most likely not enjoy a raise — we'd more likely be fired. Public servants, especially those armed with firepower and tear gas, should be held to the highest standards. Instead, they are often excused from even the most basic standards the rest of us endure.

Is this system deterring crime? Once again, the answer is a resounding no. Supporters of this concept believe that the tens of billions of dollars the U.S. spends on being the world’s largest incarcerator deters crime by keeping people with criminal histories removed from society, and/or deters criminal activity with the threat of jail.

However, this expensive and inhumane solution renders little of that true. Vera Institute of Justice research indicates that “increases in incarceration rates have a small impact on crime rates,” and may actually “increase crime in certain circumstances. In states with high incarceration rates and neighborhoods with concentrated incarceration, the increased use of incarceration may be associated with increased crime.”

Government could do far more by investing in social safety nets and services that create healthy communities from the ground up than spending more on jails and prisons.

Instead, the police are too often causing crime. Police violence is deeply racialized — this we know. And yet it should concern every American — not just the Black ones — that our tax dollars pay into a system that kills over 1,000 people annually, and injures and assaults far more. Each incident is tragic, unjust and entirely preventable. And such a reality is an insult to the democracy we claim to hold dear.

Other countries similar in development and wealth are doing far better than a supposedly exceptional America at keeping police violence minimal, if existent at all. It should offend our sensibilities each and every time American law enforcement officers harm the very communities through which they derives their power, while the system protects them from accountability or transformation.

If the police aren’t preventing crime, solving crime or deterring crime, and are far too often causing the crime themselves, we would be wise to remove our tacit approval of this institution — along with our society’s deep financial and social investments, and invest in those things that truly keep us safe.

Now is the time to ask better questions. Inquiring which detail justified the death of the latest victim of public servants is as inhumane as it is misguided. Isolated tactical conversations risk the implication that some killings by police are permissible. So I ask you, when is it permissible for the police to kill your daughter? What details would reasonably justify her death for you?

We, the people, are on the wrong end of a bad deal. These returns fail to justify our investment — because the returns are deadly, just like they were for Breonna Taylor. She saved lives. We owe it to her to save every other Breonna Taylor in her memory.