In the opening sequence of “Katrina Babies,” the new HBO documentary directed by Edward Buckles, we see quiet, expressionless Black children spinning around in rescue baskets as helicopters pull them high above the raging waters pouring into New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward. These stoic, suspended children represent more than just the reality of Aug. 29, 2005. They also symbolically foreshadow so many children's future: lives marked by disorientation and swallowed-down suffering.

Is now really the time for yet another Katrina remembrance project? For this one, absolutely.

It's been 17 years since the city’s federally constructed flood control system crumbled, leaving bodies floating in the street. Given that extensive gap and the public health crises that have since redirected our attention, is now really the time for yet another Katrina remembrance project? For this one, absolutely.

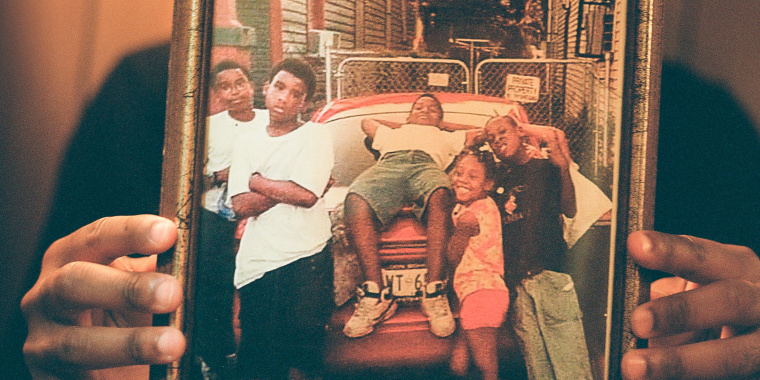

Director Buckles was 13 when his family hastily threw a few things together and fled New Orleans ahead of the storm. He was 20 and a student at Dillard University when he conceived of “Katrina Babies” and a 23-year-old high school media instructor when he started filming. Now 30, Buckles told me Thursday, “I spent all my 20s making this film.”

Black children are talked about often but rarely listened to. They are frequently discussed, pitied or pathologized, but almost never asked to speak. They are commonly the subjects of stories, but less often those stories' narrators.

But there are no talking heads in Buckles’ film. Even though most of Buckles’ interviewees are no longer children, the message remains the same: Children are the authorities of their own lives. They don’t need adults speaking about them or for them.

“I knew that would be a challenge, to not include experts who contextualize” things, Buckles said. But, he added, “I wanted us to be the experts.”

When the children of New Orleans were scattered across the country, they were often treated more like problems than people. The “Katrina babies” remember that insensitivity bitterly.

Heather Haynes was 16 when she landed at a new school. “The principal was like, ‘Do you think you’ll fit in here?’ What kind of question is that to ask a girl whose home is under 8 feet of water, ‘Do you think you’ll fit in here?’ Hell the f--- no! I don’t want to fit in here.”

When the children of New Orleans were scattered across the country, they were treated more like problems than people.

Haynes’ anger is understandable. But interestingly, few of the people Buckles interviewed expressed much visible emotion. That strange dynamic is not a coincidence.

“Yes, there is a lack of tears,” Buckles said. “I think that comes from numbness. It's not that we don't feel; it's that we felt so much that we are immune to it.”

At the same time, it’s clear that nobody ever explicitly gave them permission to cry. Miesha Williams, who was 12 during Katrina, is one of only two people we see shedding tears. And she apologizes. “I didn’t want to cry,” she says. “Sorry.”

“Have you ever talked about this before?” Buckles asks.

“No. I haven’t.”

“Why, you think?”

“I don’t know. Nobody ever asked me.”

Watching the film in 2022, after years of deadly natural disasters and a deadly and destabilizing coronavirus pandemic, it’s hard not to think about the current generation of American children. Who is tending to their emotional needs? Will they, too, grow up without anyone asking about their experiences and feelings?

New Orleanians know who the villains in the Hurricane Katrina story are: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which built shoddy levees and floodwalls it later acknowledged was “a system in name only;” former President George W. Bush and his FEMA Director Michael Brown, who dithered and dallied when the city needed rescue; a New Orleans Police Department that killed, maimed and framed innocent people and even attempted to cover up one killing by burning the body; racist know-nothings who maligned Black New Orleanians as ignorant, overly dependent and savage.

But Buckles couldn’t identify a villain for the collective disregard of Katrina’s babies. “Who do we blame? When I say, ‘Nobody asked me,’ who am I talking about?” he said. “Am I talking about my parents? Am I talking about the local or national government? I still don't know who to blame.”

But ultimately, that unanswered question doesn’t matter — nor does it blunt the power of this film. What matters is that he gives young, Black adults, who were disastrously, and at times callously, failed on a societal and institutional level, a platform to speak authoritatively about their own lives. That shouldn’t be as rare as it is.