I'm willing to admit it sounds like it can be pretty hard to be a member of Congress at times. You're forced to have a position on literally every piece of national public policy, even if what you believe and what your constituents believe don't exactly line up.

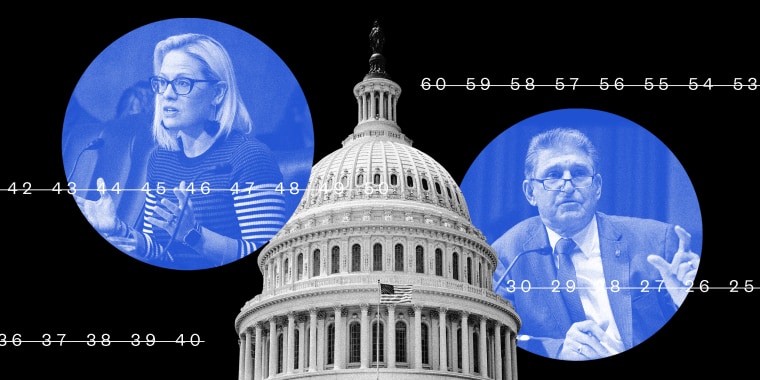

But that's the job. It's what you signed up for when you ran for election. Except, as it stands, members of the Senate have an out. And Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., is using it for all it's worth.

In a Politico profile published Friday, Sinema doubled down on her belief that the filibuster's imposition of a supermajority hurdle to legislation not only is right — it should be the basis of all legislative votes.

Not only does she want to keep the filibuster; she wants to rebuild it. And the end-around idea of overruling the parliamentarian to jam whatever Democrats want to in a budget reconciliation bill isn't going to happen on Sinema's watch, either.

"There is no instance in which I would overrule a parliamentarian's decision," Sinema said. "I want to restore the 60-vote threshold for all elements of the Senate's work."

Now, this isn't new for Sinema. Last month, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., was holding the Senate's organizing resolution hostage, insisting on a pledge from Democrats, in writing, that the legislative filibuster remain in place over the next two years. Sinema and Sen. Joe Manchin's promise not to be votes 49 and 50 to nuke the filibuster is part of what led McConnell to rescind his demands.

What gets me is that in protecting the filibuster, Sinema and Manchin are protecting themselves politically at the expense of the country.

I understand the arguments that the filibuster encourages bipartisanship, even though I wholeheartedly disagree with them. But what gets me is that in protecting the filibuster, Sinema and Manchin, D-W.Va., are protecting themselves politically at the expense of the country.

The filibuster is pernicious not just in its ability to get bills passed in the Senate; it's in its power to block bills from even coming to recorded votes. I spent a lot of time going through the cloture votes — the method of shutting down filibusters — over the last few Congresses to track how often filibusters blocked bills and nominees. As I said then, it's not a perfect method for measuring the filibuster's use these days.

Because as Adam Jentleson, author of "Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy," told MSNBC's Chris Hayes on the "Why Is This Happening?" podcast, these days the process is all conducted over email. Senate leadership sends a bill around and asks whether anyone has plans to filibuster. "Literally any staff member can reply to that email" to say their bosses object, Jentleson said. "And it's that single email that today raises the threshold of whatever bill is at stake from a simple majority to a supermajority."

That's an intentionally opaque process. It's one that cloaks how many measures are floating around that have majority support but never reach the Senate floor. And it keeps legislation from failing in the Senate in close 49-51 votes, save for a few extraordinary exceptions.

Lofty rhetoric about the Senate's historical support for the minority's rights aside, as I told Peacock host and fellow MSNBC Daily columnist Mehdi Hassan on Sunday, it's not hard to see why Sinema and Manchin are the biggest holdouts in their party when it comes to the filibuster. As the Politico article emphasized, Sinema's political support in purple Arizona depends on her political image as a maverick who isn't beholden to her party's leadership. (In this way, she's drawn many comparisons to the late Republican Sen. John McCain.)

Manchin, meanwhile, is consistently described as the most conservative member of the Senate Democratic caucus. He is serving his third term representing a state that has become only more solidly Republican since he was first elected, and the common wisdom is that if he weren't in the seat, it would be an easy GOP pickup. That has positioned him as kingmaker in Democrats' extremely narrow majority, in which every member's vote will be needed to pass anything with Vice President Kamala Harris' tiebreaker.

So you can see why neither of them would want to cast too many votes on legislation that might be too nationally popular to reject but too controversial at home to support. Absent the filibuster, they'd not only be on the record as for or against the laws in question — they'd also be the deciding votes. I can see why it's much easier to insist on dragging 10 Republicans along for any ride as political cover than be the only reason a bill stalled out.

But that can't be a reason for inaction over the next two years. Manchin and Sinema need to let legislation live or die by the majority's will. If they truly want bipartisanship to have its day again, they need to be unafraid to let bills come to final votes, even if they find themselves voting with the minority.

CORRECTION (Jan. 12, 2022, 8:11 p.m. ET): A previous version of a headline and caption with this article misspelled the first name of a senator from Arizona. She is Kyrsten Sinema, not Krysten.