Last week in New York City, a state court judge dismissed the first-degree murder convictions of two men who each served more than 20 years in prison for the 1965 killing of Malcolm X. One of those wrongly convicted men wasn’t even alive to hear the government apologize. Cyrus R. Vance Jr., the current Manhattan district attorney, offered an apology on behalf of law enforcement which he stated, “failed the families of the two men.”

The exonerations of Muhammad A. Aziz, now 83, and Khalil Islam, who died at 74 in 2009, leave us with more questions than answers.

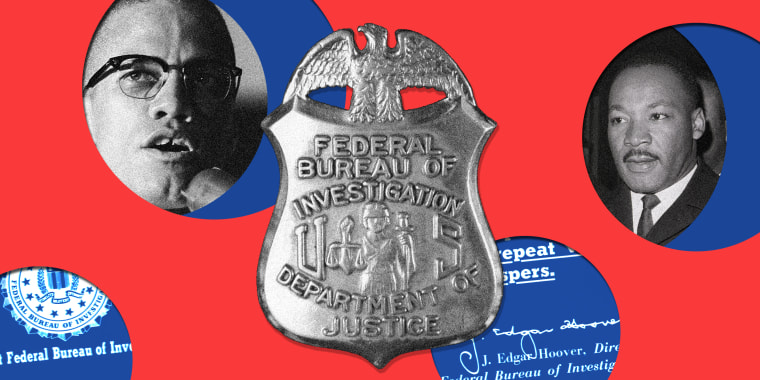

Now, 56 years after the murder of the fiery African American minister and former spokesman for the Black nationalist group, the Nation of Islam, the exonerations of Muhammad A. Aziz, now 83, and Khalil Islam, who died at 74 in 2009, leave us with more questions than answers, especially questions related to the conduct of law enforcement agencies. Previous suspects who were never arrested are dead. So we shouldn’t limit ourselves to asking, “Who did it?” The bigger question is “Why was the truth suppressed?”

A 22-month joint investigation by Vance’s office, lawyers for Aziz and Islam, the Innocence Project and civil rights attorney David A. Shanies, revealed that prosecutors, the New York City Police Department and the FBI withheld evidence that would likely have led to the two men’s acquittal. Their findings seemed to support what a third man convicted in the shooting death of Malcolm X has been saying all along. Mujahid Abdul Halim, an 80-year-old former member of the Nation of Islam, confessed in open court that he was one of the killers, but he also emphatically asserted that Aziz and Islam were not the other men involved.

While the recent investigation led to the formal exonerations, the credit for prompting the government’s action — or maybe publicly shaming officials into action — belongs to amateur historian, activist and investigative journalist Abdur-Rahman Muhammad whose Netflix docu-series “Who Killed Malcolm X?” exposed glaring gaps in the case.

Some of the investigative findings that led officials to conclude that Aziz and Islam were wrongfully convicted include:

- FBI documents implicating other Nation of Islam suspects and lessening suspicions about Islam and Aziz, then known, respectively, as Thomas 15X Johnson and Norman 3X Butler.

- State prosecutor’s notes revealing a failure to disclose the presence of undercover officers at the time of the shooting.

- NYPD files documenting that a New York Daily News reporter received a call the morning of the shooting from someone indicating Malcolm X would be murdered.

- An interview of a still-living witness who continued to confirm Aziz’s alibi: that he was home when the shooting happened.

We may never learn who the other killers were. But the bigger question may be why this case was, at best, horribly flawed – and at worst – deliberately deceiving. Deborah Francois, lawyer for Islam and Aziz, told The New York Times, “This wasn’t mere oversight. This was a product of extreme and gross official misconduct.”

While the recent inquiry found no evidence that the police or FBI conspired to kill Malcolm X, their conduct raises important questions: Did authorities have intelligence indicating Malcolm X, who’d left the Nation of Islam and excoriated its leader Elijah Muhammad for fathering eight children with six teenage girls, was being targeted for murder by the Nation of Islam but fail to act on it?

Wiretaps now require court authorization, and undercover operations must adhere to high-level oversight.

Malcolm X was perceived as a dangerous radical who, while he served as the most outspoken member of the Nation of Islam, had promoted the group’s theology of innate black superiority over whites and had, at least then, referred to Caucasians as “devils.” Is it possible that law enforcement, aware of the Nation of Islam’s growing animosity toward Malcolm X, found it convenient to ignore signs of the group’s plans to assassinate him, thereby allowing the elimination of a radical firebrand it viewed as a security threat?

Was the failure to disclose the presence of undercover officers at the site of the shooting merely a security safeguard to facilitate continued covert operations against the Nation of Islam, or, is it possible those undercover officers had learned of the plans to kill Malcolm X and did nothing to stop it from happening?

Did the original murder investigators deliberately ignore a strong suspect they had identified – a Nation of Islam “enforcer” named William Bradley – because Bradley, or other suspects, were police informants?

Or was the original investigation lacking rigor because the mostly-white law enforcement organizations and the mostly-white media organizations of that day not care much about a crime within the Black community, especially one that claimed the life of a leader who had spoken so negatively about white people?

Maybe the most important question that remains is whether anything has changed to make this kind of law enforcement misconduct less likely. Even as we continue to question the credibility of our justice system, nearly 60 years after Malcolm X was assassinated, there are encouraging developments. Police departments suspected of unlawful investigations are subject to U.S. Department of Justice patterns and practices inquiries. At the FBI, the abuses of power by former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who ruled his agency for 40 years and was in charge when Malcolm X was killed, led to strict regulations governing domestic operations. Wiretaps now require court authorization, and undercover operations must adhere to high-level oversight.

Layers of review within the FBI, the Justice Department and Congress don’t eliminate possible wrongdoing, but greatly reduce the chances. All FBI new agent and intelligence analyst classes study the dangers of authoritarian regimes and travel to the Holocaust Museum. Those same classes include in-depth study of the FBI’s abuses during its investigation of Martin Luther King, and those employees pay a visit to the MLK Memorial in Washington. The FBI has an official historian who chronicles the agency’s past abuses and shares them in presentations to classes at the FBI Academy.

The Manhattan DA’s office did the right thing in leading the inquiry that exonerated Aziz and Islam. It’s proof that the system, though flawed, is capable of correcting itself. Moving forward, we’ll need proof that measures are implemented to trigger regular review of police and prosecutor files in controversial convictions where contrary evidence exists. We shouldn’t have to rely on Netflix to force corrective court actions that come way too late to be construed as anything resembling justice.