TikTok has become a powerful vehicle for young creators to expand their reach and even earn an income. But it appears to be much easier to do so if you’re white.

Black creators and other creators of color have been struggling to receive the same kind of recognition, although they are often the ones who create the original dance routines that go viral — a lot of times without attribution.

Since Juneteenth, a growing number of Black TikTok users have been staging a boycott of sorts, refusing to post new dance routines on the platform. As dancer Erick Louis, one of the first to announce the work stoppage, stated in his post: “This app would be nothing without [Black] people.”

This dispute on TikTok is the latest chapter in a problematic cycle within a society that appropriates Black culture for mainstream art, music, food, entertainment and other pop culture trends for profit without sharing that profit — or credit — with the original Black architects. As a result, Black creators face glaring inequalities, including in the internet marketplace, where visibility is the most valuable currency. Even the most influential Black creators have difficulty finding competitive sponsorships.

Today, Black Americans continue to face myriad barriers to building wealth. That ability is fundamentally connected to attribution and ownership. If creators of color are not credited for their creations, they cannot prove ownership. That’s what the current TikTok strike addresses.

As Sarah J. Jackson, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, told NPR, “A large swath of American popular culture comes from Black culture and that is before the internet even existed.”

“We can take any historical period and look at popular culture,” she added, “and see the ways in which white folks who have access to mainstream capital and mainstream media … were drawing inspiration from the art forms and creative forms of Black folks.”

During the 19th and 20th centuries, white performers in the United States often used blackface in public performances. The practice, which still occurs today, became a means for many white performers to earn a living through racist distortions. White performers’ use of blackface fueled a massive industry in the aftermath of the Civil War throughout the country. The first major American “talkie” film, “The Jazz Singer,” for example, prominently featured a blackface performance by the white entertainer Al Jolson.

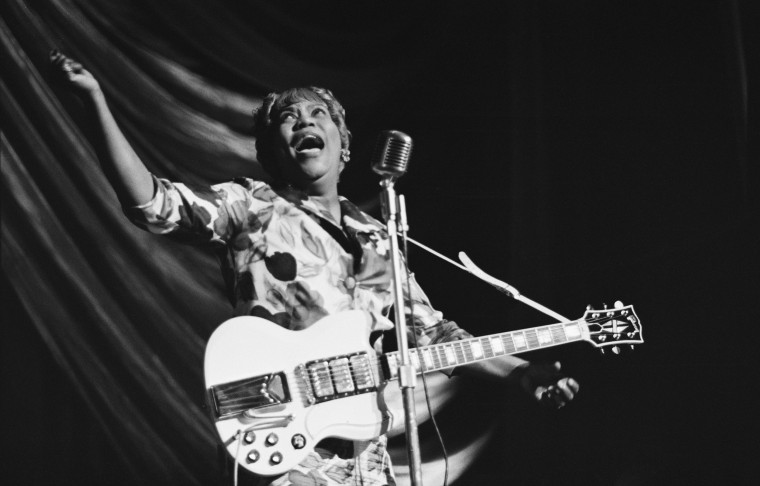

In rock 'n' roll history, mainstream narratives tend to focus on white musicians even though Black musicians were instrumental in its shaping. Many Americans are still unaware of the contributions of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, dubbed the “Godmother of Rock 'n' Roll” because of her extraordinary influence. Born in 1915 in Cotton Plant, Arkansas, Tharpe started to learn how to play the guitar around the age of 4. Her unique style of playing the guitar — straying from the traditional chords — set her apart.

According to biographer Gayle Ward, Tharpe was “gospel’s original crossover artist, its first nationally known star, and the most thrilling and celebrated guitarist of its Golden Age” and greatly influenced many well-known artists including Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash. But until recently, Tharpe’s talents and contributions were overshadowed because she did not fit the mold of what many expected a pioneer of rock 'n' roll to look like: a young, white man.

We’re still seeing strong echoes of Tharpe’s plight today. In May 2020, Black creators called for a “Blackout” on TikTok to bring greater awareness to unfair censorship practices and content suppression. Although the company responded by pledging to make changes to support Black creators and vowed to provide a space for them to be “safe,” these harmful practices have persisted.

Before that, young Black creatives on TikTok’s now-defunct predecessor, Vine, spoke out when they witnessed their original content being widely used without attribution. They resisted the practice then, as they are resisting now.

"Black folk have always been aware that we’ve been excluded and othered,” Erick Louis told the Washington Post. “Even in the spaces we’ve managed to create for ourselves, [non-Black] people violently infiltrate and occupy these spaces with no respect to the architects who built it.”

Louis’ assessment could easily describe any period of American history. Despite their many contributions to shaping American culture, Black people are often overlooked — even as white Americans draw inspiration from their creative work. The TikTok strike is the latest effort to bring an end to this longstanding practice. Perhaps it is just the spark we need to ensure Black creators finally receive their due.