On Aug. 1 in Wyoming, Michigan, Eric Brown, an African American realtor, was showing a property to his client Roy Thorne, also African American, when the two were handcuffed by police officers after a neighbor called the police.

The Black homeownership rate is 30.5 percent lower than white Americans and 22 percent lower than the national homeownership rate.

When officers arrived on the scene, they drew their guns on Brown, his client, and his client’s 15-year-old son and ordered them out of the house. The three were uncuffed and released after officers determined they were not in violation of the law. While city officials deny allegations of racial profiling, Black residents in the city point to a pattern of racial exclusion and discrimination.

The majority-white city of Wyoming — of which only 7.8 percent of the residents are Black — is not the only site of racial profiling and housing discrimination, a persistent problem the Biden administration is now working to address. The first step has been reviving anti-discrimination regulations that former President Donald Trump gutted. But eradicating housing discrimination requires much more than that.

Each year, thousands of Black residents encounter roadblocks when seeking housing, including violence and intimidation. In October 2020, a white man in the Detroit suburb of Warren fired a gun into the home of a Black family, threw a rock through a window, slashed their tires, and terrorized neighbors before he was arrested. Last month, a white man in Mount Laurel, New Jersey was arrested after harassing several of his neighbors of color. Prosecutors found that the 45-year-old not only yelled racial slurs at his neighbors but also wrote threatening notes, smeared feces on their windows, and threw rocks at them.

Despite some of the tangible gains of the Civil Rights Movement, including the dismantling of Jim Crow on the national level and the expansion of Black political rights, housing remains a racial battlefield in the United States. According to a 2019 study, 16.8 percent of Black Americans live in majority Black neighborhoods.

The Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, reinforced this point in a 2020 letter to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), explaining that “Today a typical white person lives in a neighborhood that is 75 percent white and 8 percent Black, while a typical Black person lives in a neighborhood that is only 35 percent white and 45 percent Black.”

This reality is not coincidental; it’s by design. Housing discrimination has kept Black and brown families out of many neighborhoods and continues to contribute to the current racial gap in homeownership. According to the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, the Black homeownership rate is 30.5 percent lower than white Americans and 22 percent lower than the national homeownership rate of 63.7 percent.

More than 60 percent of those displaced by these urban renewal programs were Black Americans, Latinx people, and other racial minorities.

Housing discrimination and other exclusionary practices at the local, state, and federal level reinforce segregation in cities. In her groundbreaking book “Race for Profit,” historian Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, a professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, has noted that these disparities were “abetted by the failure of the federal government, in any historical period, to enact rigorous regulatory compliance with civil rights laws.”

Consider the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), for example. From 1934 to 1962, the FHA and the Veterans Administration administered more than $120 billion to fund urban renewal projects in various cities across the nation. The FHA loans and other federal funds made available to cities to help them become economically viable ultimately lined the pockets of private developers — at the expense of poor Black people and other marginalized groups.

Less than 2 percent of the new real estate developed through these programs was made available to Black Americans and other marginalized groups. These federally funded projects led to the destruction of 20 percent of city housing units that were occupied by Black people. More than 60 percent of those displaced by these urban renewal programs were Black Americans, Latinx people, and other racial minorities.

Federal and state policies reinforced housing discrimination. And so did local resistance. In June 1925, African American physician Ossian Sweet and his wife, Gladys, bought a house in a working-class, mostly white neighborhood in Detroit, Michigan. Fearing white resistance to their arrival, the Sweets delayed their move until September. When they attempted to move in on Sept. 8, their fears became real when white residents gathered outside the home in protest to the family’s arrival. When Ossian Sweet’s brother, Otis, arrived with a friend, the crow of white neighbors began attacking the family. In the commotion, shots were fired, killing a member of the white mob and wounding another. Police arrested Ossian, Gladys, and the other adults in the home — and charged each of them with first-degree murder.

The NAACP rallied around the Sweets, arguing that they had the right to defend their home. When the Sweets were eventually absolved in court — the first jury was unable to reach a verdict and the second case resulted in an acquittal — African Americans across the country celebrated their win. The outcome of the cases represented a blow to racial segregation in American housing.

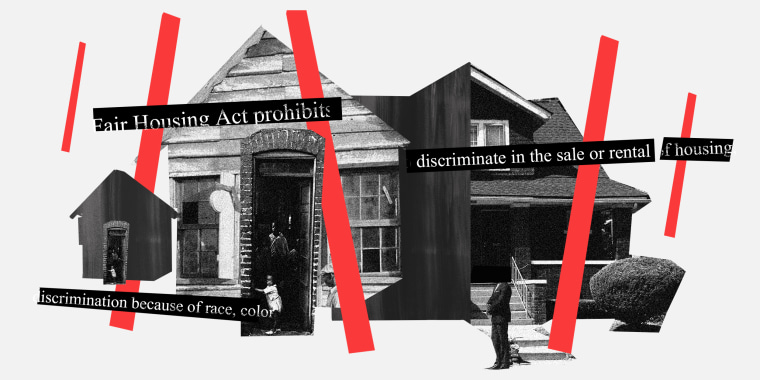

Decades later, the 1948 decision Shelley v. Kraemer decision effectively outlawed restrictive covenants that were aimed at keeping Black people and other marginalized groups out of certain communities. The 1968 Fair Housing Act further reinforced the importance of equal access to housing for all, regardless of race and ethnicity.

This history of discrimination and exclusion has left devastating consequences.

Yet housing discrimination persists. As President Joe Biden pointed out in his memorandum to HUD earlier this year, “racially discriminatory housing policies [have] contributed to segregated neighborhoods and inhibited equal opportunity and the chance to build wealth for Black, Latino, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and Native American families, and other underserved communities.”

This history of discrimination and exclusion has left devastating consequences. As Biden reminds us, “the Federal Government has a critical role to play in overcoming and redressing this history of discrimination and in protecting against other forms of discrimination by applying and enforcing Federal civil rights and fair housing laws.”

Much like past instances when white Americans have called the police on Black people for simply living their lives — for eating or bird-watching, for instance — the incident in Wyoming is yet another example of how racism permeates all aspects of American society. Let’s hope this experience — and the continued pattern of exclusionary practices in housing across the United States — creates a new sense of urgency for the administration.