For some, it's a spiritual calling, an exercise regimen, or a lifestyle choice. But for a growing number of people in the United States, yoga is a job. It's just not a job that happens to pay very well.

Just ask Eve, who spent eight years working as a full-time yoga instructor in New York, including seven and a half years during which she had a steady gig at one of Manhattan's biggest studios. Eve -- who asked not to be identified by her last name because she still attends classes at the studio -- said she and her co-workers had to struggle in order to scrape together a livable income.

"There hasn't been a change in the compensation structure since 1998, I would say," she said of her former employer. "And as you know, the cost of living in New York has just continued to skyrocket."

The per-class amount which Eve was paid depended on the number of people in the class; if nobody showed up, she didn't earn a dime, despite the time she spent traveling to the studio. On top of that, she was required to wear the studio's brand of yoga attire during classes, purchased with her own hard-earned cash (albeit with the help of an employee discount). But the biggest expense was the teacher training, which cost Eve $12,000 and took weeks of grueling, full-time work to complete.

"I had colleagues who put the teacher training on their credit cards and were still paying it off two years, five years later," said Eve. She had to work as a full-time yoga instructor for about a year before she broke even.

The industry group Yoga Alliance only grants accreditation to teacher training courses which include a minimum 200 hours of instruction, but Eve's studio required that all teachers go through a far more intensive program. She paid her future employer thousands of dollars to go to an upstate retreat, where she worked and studied from 7 am to about 10 pm, six days a week, for four weeks. When she arrived on the first day and saw the schedule, "I actually started to cry," she told msnbc.

Not all yoga training is as costly and intensive as the one Eve attended, but in most other respects she had a fairly typical yoga teaching experience. Adri Frick, who owns the California studio Type A Yoga, said the Bay Area yoga industry is characterized by precarious, low-paying contractor gigs.

"It saves the employers because they get to evade taxation law, and so they don't have to pay for workers comp," she said, regarding the widespread practice of paying teachers as independent contractors. "They also just save in accounting and administrative overhead by not keeping track of a lot of the finances."

The casual, gig-based nature of yoga teaching makes it hard to gather hard data about the profession, and estimates of its average annual salary range from $45,000 to roughly $30,000 or less. A yoga teacher's income may vary wildly from month to month, as practitioners go on vacation or decide to stay home due to inclement weather. And on top of all that, a flood of new teachers has made the competition for teaching slots more intense than ever. In 2005, the North American Studio Alliance estimated that there were 70,000 yoga teachers in North America. But since then, yoga practice has only grown in popularity, and the number of teacher training programs has risen as a result.

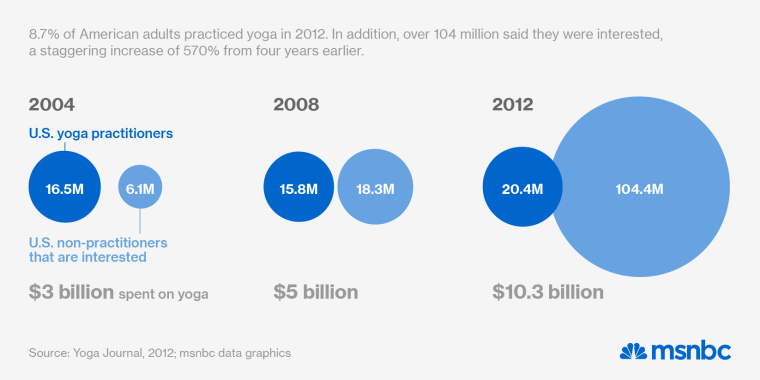

"Yoga obviously is growing, but it's not just growing," said Yoga Alliance President and CEO Richard Karpel. "The rate of growth, I think, has increased over the past year or two."

The growth is expected to continue over the next several years, but it's unclear whether it can keep up with the proliferation of new teachers. A large teacher training school may "turn out graduates via intensive programs at a rate of 30-50 every three months," according to Frick. In order to scrape together a full-time income, those teachers must then pick up gigs at a range of studios and venues in their home cities.

For yoga instructors, performative tranquility is a big part of the job. But underneath the serene exterior, the pressure of trying to pay the bills can be extremely stressful, especially given the amount of work teachers are forced to do off-the-clock. Traveling from gig to gig is a big part of any yoga teacher's job, but so is offering informal counseling to students.

"We aren't just fitness instructors," said Frick. "We stay after class to talk to people who are dealing with emotional concerns. [...] So sometimes that means you're getting texts at 3:00 on a Friday from someone who just got in a car accident, or you're getting an email from someone who had a tough weekend."

Some teachers, especially those without Yoga Alliance-certified training, may not be qualified to deal with their students' emotional or spiritual dilemmas. But even those who are equipped to provide counseling will inevitably wind up doing almost all of that counseling after class hours, without additional pay. The rise of online coupons, such as those offered by Groupon and LivingSocial, has also claimed a chunk of some yoga teachers' salaries, since studios don't necessarily pay them the full rate for students who take advantage of those discounts.

In many respects -- the low pay, the gig-based nature of the job, and the unpaid overtime -- yoga is little different from other freelance professions in the new, service-based American economy. More than one person interviewed by msnbc compared teaching yoga to being a part-time adjunct professor, with all the job insecurity and irregular pay that implies. And like many low-paying service jobs, the field of yoga instruction is dominated by women. According to the Yoga Journal's 2012 Yoga in America survey, 82% of American yoga practitioners are women. The survey didn't track the gender breakdown for teachers specifically, but only one of the dozen or so yoga instructors who replied to msnbc's request for interviews was male.

Many of the industry's most prominent gurus, however, are male. And in recent years, the yoga community has been hit with high-profile allegations of sexual harassment or sexual assault. The most infamous case involved Bikram Choudhury, the founder of Bikram Yoga, who has been sued multiple times over allegations of rape and harassment. Other yoga instructors accused of harassment include Aspen, Colo. teacher Steven Jon Roger and Austrian guru Kausthub Desikachar. John Friend, the founder of Anusara Yoga, has been accused of "sexual misuse of power and pension fraud" according to the site Well and Good, though he has only admitted to having an affair with a married student.

Karpel, the head of the Yoga Alliance, said that sexual harassment is "absolutely not" widespread in yoga.

"I think you've got two yoga teachers who got to kind of guru status, and there's danger in that, but that's pretty rare," he said of Friend and Choudhury.

The more immediate problem for most yoga teachers is just making ends meet. According to Marthe Weyandt, the author of a 2013 article called "You're Never Going to Make a Living as a Yoga Teacher," that's in part due to a certain deeply ingrained belief that "it's not 'yoga' to ask for adequate compensation."

"I think there's this sort of reluctance to talk about money, rooted in the principles [of yoga]," said Weyandt. "But obviously, since it's your career, you need to be getting paid enough to afford food, and rent, and basic things."