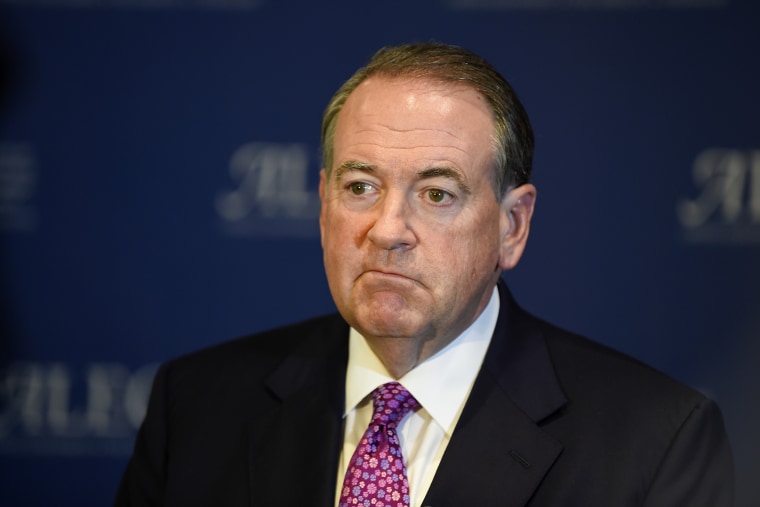

When Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee claimed last weekend that President Obama would ultimately “take the Israelis and march them to the door of the oven,” the former Arkansas governor wasn't being simply hyperbolic about the merits of the Iranian nuclear deal. He was banking on the idea that there is a rift between the Democratic president and the American Jewish community -- an opening presumably ripe for political exploitation.

The attempt to drive a wedge between Obama and American Jews has long been part of the Republican playbook. But a closer look at the history of Jewish voting patterns shows why, exactly, the GOP gambit continues to fail.

RELATED: Jewish groups react to Mike Huckabee’s ‘oven’ remarks

It is a widely-recognized fact that American Jews tend to be liberal, despite falling into an affluent socioeconomic bracket that normally leans conservative. In the 1920 presidential election, when Americans backed Republican Warren Harding over Democrat James Cox by an unprecedented 60-to-34 margin, 38% of American Jews cast their ballots for the Socialist candidate, Eugene Debs. Debs, who made his final presidential run from prison after being arrested in 1918 for speaking out against America’s involvement in World War I, received only 3% of the general popular vote.

American Jews became solidly Democratic voters in the 1930s, as Franklin Roosevelt's bold liberalism moved the party decisively to the left, guaranteeing 80-90% of the Jewish vote to every Democratic presidential candidate in nearly every election from 1932 to 1968. Jewish voters broke from that trend on only three occasions: Twice in the 1950s, when personal admiration for Republican Dwight Eisenhower overcame other ideological considerations (as happened for many other normally Democratic groups), and in 1948, when 15% of American Jews abandoned President Harry Truman -- despite his instrumental role in recognizing the State of Israel only six months earlier -- to support former Vice President Henry Wallace, the standard-bearer for the socialist Progressive Party. (Truman still received 75% percent of the Jewish vote that year.)

American Jews’ overwhelming support for Democrats began to weaken in the early 1970s. Despite playing a disproportionate role in the rise of the New Left, the intra-party movement that pushed Democrats toward even more liberal positions, many Jews had grown more conservative as they had assimilated into the American mainstream. Although this was partially due to the New Left’s increased willingness to criticize Israel, it can also be traced to the waning of systematic anti-Semitism and the growing pattern of Jews moving out of cities and into the suburbs.

As a result, Jewish support for Democratic presidential candidates dropped to a range of 64-to-71% in the five presidential elections after the Democratic Party became widely associated with the New Left (even though its presidential candidates didn’t always subscribe to New Leftist ideals). The one exception was the election of 1980, in which Jimmy Carter won just 45% of the Jewish vote. Carter still won more Jewish votes than Ronald Reagan (who scored 39%), but his stance on Israel, perceived ideological flip-flopping, and general unpopularity hurt him at the ballot box.

RELATED: Obama: Huckabee comment would be 'ridiculous if it wasn’t so sad'

Fortunately for Democrats, Jewish voters began to return to the fold after the nomination of Bill Clinton in 1992, who pushed the party brand toward a more left-of-center ideology and reestablished American Jews as a reliably 70-to-80% Democratic voting bloc. In years when the Democratic presidential candidate won by a landslide -- such as Clinton in 1992 and 1996 or Obama in 2008 -- Jewish support was on the higher end of that spectrum. When the Democrat either lost or won by a smaller margin, Jewish support trended lower, with Obama garnering the weakest showing in 2012 with 69%.

Rather than indicating softening support, however, Obama's shakier showing with Jewish voters in 2012 suggests the limited effectiveness of Republican attempts to drive a wedge between American Jews and the Democratic president. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his Republican allies did all they could to undermine Obama's outreach to the Jewish community during the election, playing up his well-known personal friendship with the Republican candidate, Mitt Romney. The effect was not inconsequential -- Jewish support for Obama dropped nine points from 2008 to 2012 -- but seven in 10 Jewish voters still punched their ticket for Obama.

"Being an American Jew means more than just supporting Israel."'

Of course, Huckabee isn’t alone in mistaking this drop in support for deeper hostility. "You know, I think I am the closest thing to a Jew that has ever sat in this office," the president reportedly told David Axelrod, then one of his senior advisers. "For people to say that I am anti-Israel, or, even worse, anti-Semitic, it hurts."

Obama is absolutely right about one thing: He may very well be the closest equivalent to a Jewish president that America has had. Jews in the United States have long identified with African-Americans and the civil rights movement due to their own historical experience facing widespread prejudice. It’s hardly a coincidence that the campaign which elected Obama as America’s first black president was run by two Jews (David Axelrod and David Plouffe), or that he has surrounded himself with Jewish advisers throughout his presidency. The president's support for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict -- openly opposed by several GOP candidates -- was backed by 80% of American Jews as of last year (the same poll found his support among Jews to be at 57%, compared to 43% of the general population).

In short, the president's reputation with the Jewish community is just fine. If Republican politicians want to win Jewish votes, they'll have to do better than rhetorical bomb throwing and aligning themselves with Israel's current right-wing government. They’ll need to recognize that being an American Jew means more than just supporting Israel; it means embracing the values of pluralism, religious tolerance, and humanitarianism that has made America such a welcoming home for minorities like Jews in the first place.

Matthew Rozsa is getting his PhD in American history from Lehigh University and is a regular contributor to The Daily Dot, Salon, and The Good Men Project.