It took six months of strife, setbacks and vicious partisan sniping, but Obamacare has emerged from the first open enrollment period poised to become an enduring feature of American life. New health care marketplaces are up and running (at varied speeds) in all 50 states. Public approval is starting to recover after crashing with the federal enrollment website last fall. And roughly 10 million previously uninsured people have now gained basic health security — the largest such expansion since the advent of Medicare and Medicaid in the mid-1960s.

For those who support health care equity, a big drink is in order. But it should include a shot of espresso, because the challenges ahead are still daunting. Nearly half of all states have so far refused to expand Medicaid, denying needed coverage to 5 million low-income people. The federal courts are still considering legal challenges that could eviscerate the law. And though public acceptance is growing, people who could benefit from Obamacare still harbor fears and misconceptions that the Right is well-prepared to exploit in next fall’s midterm elections. Here’s a brief to-do list for health care advocates in the months ahead.

Salvage the safety net

As signed into law four years ago, the Affordable Care Act included two basic provisions to expand access. It expanded Medicaid to cover anyone earning less than 139% of the poverty wage ($16,105 for an individual, $23,850 for a family of four), and it provided tax credits to subsidize private health insurance for anyone living between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level.

The Supreme Court blew a hole in the first provision in 2012 by turning the Medicaid expansion into a state option rather than a federal mandate. And as many analyses have shown, the states now opting out the expansion are the very ones whose residents most desperately need the assistance. The results of a newly released Gallup poll crystallize the paradox. Of the 11 states where people are least able to afford needed care, only four are accepting federal dollars to expand Medicaid.

If history is any guide, that resistance will soften as the refusal states suffer for their obstinacy. Twenty-four states opted out of Medicaid completely when the feds launched the program in 1966. All except Arizona and Alaska were taking part by 1970, and even those stragglers eventually came around. A number of red states are now breaking ranks to expand Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, but some are proposing changes to the program that could make it less effective.

Under a waiver approved in December, Iowa can now charge Medicaid enrollees up to 2% of their income in annual premiums and another 5% of their income in copayments. Arkansas, Arizona and Michigan have included less onerous user fees in their expanded Medicaid programs, and several of the refusal states (Indiana, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Tennessee) are now proposing expansion plans that include similar cost-sharing provisions.

The administration is trying to accommodate these innovations — even limited coverage is better than none at all — but federal officials will have to draw firm lines to protect Medicaid’s integrity. As a team of health care experts cautioned in the New England Journal of Medicine last week, copayments can keep low-income patients from seeking needed care — and insurance premiums are the main reason poor people can’t afford coverage in the first place. The trick is to expand state buy-in without punishing the poor in the name of reform.

Protect premium assistance

If the Supreme Court’s 2012 Medicaid decision weakened one leg of the health care law, a separate legal challenge could amputate the other one, effectively killing the whole health care law. In court battles playing out in Virginia and Washington, D.C., plaintiffs backed by the Competitive Enterprise Institute seek to bar all marketplace subsidies in the 34 states where the feds are administering health-insurance exchanges.

The dispute centers on a single phrase in the Affordable Care Act. As written, it says the federal government will extend tax credits to qualified consumers who buy health coverage through insurance exchanges “established by the state.”

The plaintiffs claim that Congress meant to reserve the tax credits for people living in states that built their own exchanges — a feat that only 14 have attempted. By their logic, Congress conceived the consumer subsidies as a weapon to punish states for letting the federal government run their insurance exchanges. The IRS is thus violating the law by extending the tax credit to all Americans living between one and four times the poverty level.

In January, D.C. District Court Judge Paul L. Friedman demolished that argument, writing that Congress “clearly intended to make premium tax credits available on both state-run and federally-facilitated exchanges.” The disputed phrase might suggest otherwise if ripped from its context, he conceded, but the Affordable Care Act says nothing about reserving affordable health care for certain states. Its history, structure and language show that the tax credit — and the option of a federally facilitated insurance exchange — were intended simply to expand participation.

The case, known as Halbig v. Sebelius, is now before the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, where a three-judge could still reverse Friedman’s ruling. And as University of Chicago health policy analyst Harold Pollack shows in a recent blog post, the exchanges would quickly collapse if that happened. The 87% of exchange participants now receiving federal financial assistance would lose it, making even the lowest level of marketplace coverage unaffordable. That would effectively nullify the individual mandate (the government can’t require people to buy coverage beyond their means) — and the loss of enrollees would push individual insurance rates into the stratosphere.

“I trust that no court would be reckless enough to wreak such havoc on such a flimsy basis,” Pollack writes. “Yet ... you never know what might happen within a judicial system that is, itself, conspicuously polarized on ideological lines.”

The D.C. Circuit Court’s conspicuously polarized judges heard oral arguments in Halbig v. Sebelius last week. A ruling is expected later this spring. The Virginia case, King v. Sebelius, is now before the Fourth Circuit appeals court, where oral arguments are scheduled for May 31. If either court goes nuclear, only Congress or the Supreme Court will be able to salvage the health care law.

Strengthen public awareness

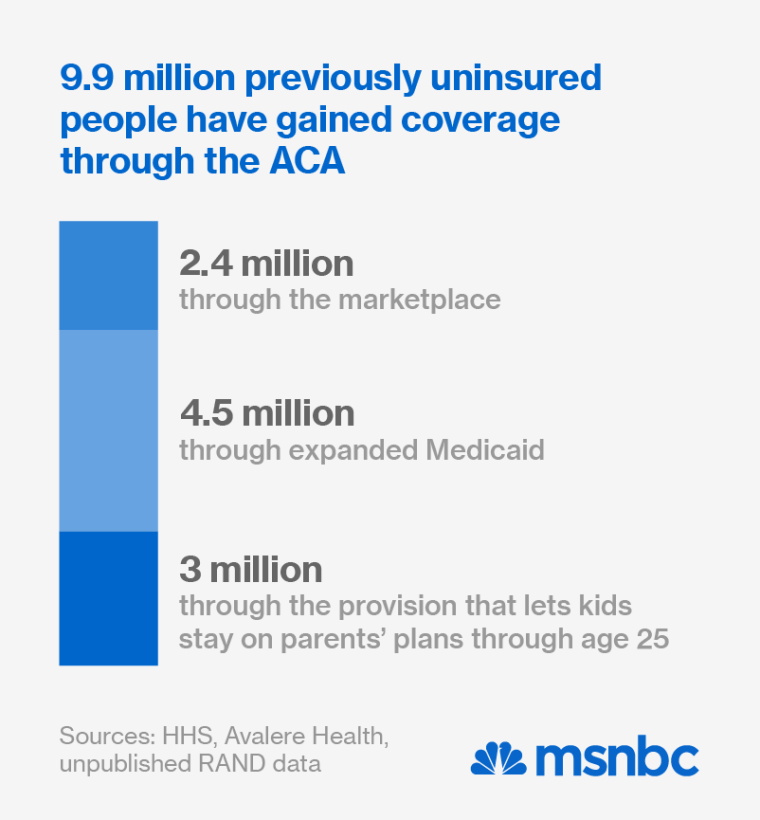

It’s not just a do-gooder’s dream. Besides fulfilling a fundamental human right, every surge in enrollment gives the Affordable Care Act a layer of political armor. Some 7.1 million Americans — including 2.4 million who were previously uninsured — now have affordable coverage through the exchanges. The expansion of Medicaid is protecting millions more from bankruptcy and preventable illness. The Congressional Budget Office projects that 24 million people will be insured through the exchanges alone by 2017, and that the number of uninsured Americans will decline by a third — from 45 million to 30 million. Politically, taking that coverage away would be a fool’s errand.

But the surges won’t happen spontaneously. Only 37% of Americans viewed the health care law favorably in the Kaiser Family Foundation’s March tracking poll. A third of the uninsured still hadn’t heard that coverage is now mandatory for most people, and 61% didn’t know that this year’s enrollment period would end on March 31. To fulfill the law’s promise, and strengthen it politically, the Obama administration must improve that record.

In a report released Tuesday, the advocacy group Families USA lays out 10 shrewd strategies for strengthening outreach and enrollment. They include hiring more navigators, retooling healthcare.gov to accept applications in languages other than English and Spanish, using SNAP (food stamp) records to streamline Medicaid enrollment, and timing the annual enrollment period to coincide with the tax-filing season, when consumers are most likely to review their own risks and opportunities.

“There are still tens of millions of Americans without health coverage,” Families USA director Ron Pollack said during a Tuesday press briefing on the new report. “If we build on the success of the first enrollment period, we can sustain its momentum.”