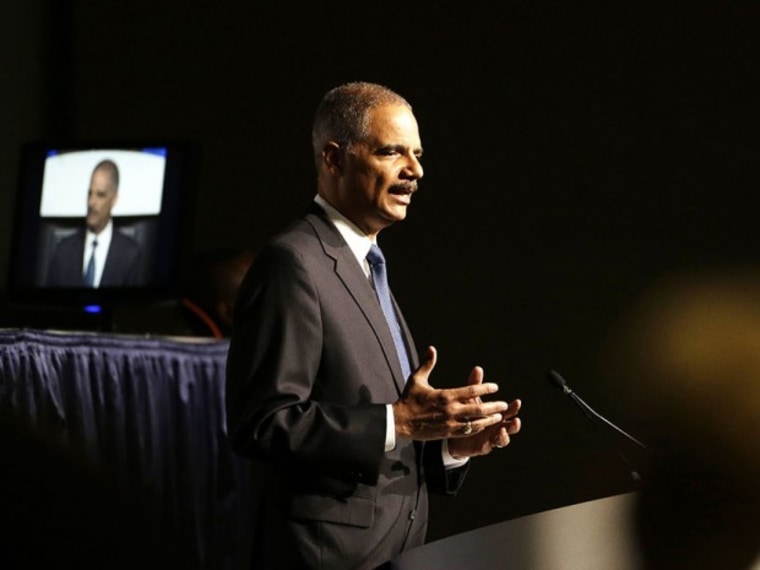

Attorney General Eric Holder gave a remarkable speech this week explaining how narcotics policy and sentencing cut to the core of the most important criminal justice issue of our time.

“As the so-called ‘war on drugs’ enters its fifth decade, we need to ask whether it, and the approaches that comprise it, have been truly effective," he said. "With an outsized, unnecessarily large prison population, we need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter, and rehabilitate—not merely to warehouse and forget.”

Holder also said, powerfully, that the disproportionately long sentences of black male offenders “isn’t just unacceptable—it is shameful.”

As Holder’s speech recognized, the Trayvon Martin case has focused President Obama on issues of race and crime. This administration clearly knows there is a problem to be solved within the federal system and the attorney general movingly described the shape and scope of the problem. Sadly though, the measures Holder announced to deal with that issue were striking in their lack of ambition or imagination. The speech did not even mention the presidential power crafted by the framers specifically for such injustices: Clemency.

There was funding for law enforcement and support for proposed legislation that has little chance to get through a Congress that can’t even deal with the sequester. Then Holder made three significant policy announcements relating to over-incarceration. In the first, he required United States attorneys to develop local guidelines for what cases should be accepted for prosecution. This is no great revelation—most offices already have such guidelines. The second change related to allowing a relatively small number of elderly inmates to receive compassionate release.

The third policy directive, which has received the most attention, changed the Justice Department's charging policies so that some low-level defendants will be less likely to face mandatory minimum sentences in narcotics cases. While this is significant and good, it probably will not affect as many cases as some reformers hope. It still gives a lot of leeway to prosecutors and disparities will continue to exist based on their differing attitudes. More importantly, a large number of these low-level cases are subject to a statutory “safety valve” which already gives prosecutors the ability to evade mandatory minimums.

These remedies address only a thimbleful out of the ocean of tragedy that misguided drug policies have created.

Hopefully, further initiatives will be announced. The first, and most obvious, would be a vigorous use of the clemency power to free those who continue to serve long federal sentences under sentencing schemes the nation has abandoned. Through Holder’s speech, the administration took credit for 2010’s Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced threshold amounts for mandatory sentences in crack cocaine cases.

Before that legislation, the thresholds were triggered by (at the lowest level) 500 grams of powder cocaine or just five grams of crack. This 100-to-1 ratio resulted in nonsensical, lengthy sentences that were reserved almost exclusively for African-American defendants. In the end, all three branches of government rejected the 100-to-1 scheme.

That rejection means little to the thousands of Americans who continue to serve long sentences under the law that contained that ratio prior to reform. The Fair Sentencing Act was not retroactive. That means that the only realistic path to fulfilling the important principle Holder articulated so well (that “we need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter, and rehabilitate—not merely to warehouse and forget”) is through the president’s pardon power. If the administration really believes in this principle, the next step should be a mass commutation of those prisoners’ sentences.

This is the last, best chance for Obama to show meaningful boldness to correct this wrong. Such a large number of clemency petitions will require significant process to be established; it can’t wait until the last days of the administration.

If Holder and Obama are thinking of their legacies, the pardon power would be a good place for firm action. As it stands, this administration is the least active of any modern presidency in the use of this important presidential tool. Of thousands of commutation petitions, many from over-sentenced black defendants, this president has granted exactly one.

The use of the pardon power isn’t just a latent option for the president: It is a constitutional responsibility to use clemency in the face of injustice, just as much as it is a constitutional responsibility to use military force as commander in chief in the face of a military threat to our nation.

Given the obviousness of this injustice, and the consensus on its importance, it is time for President Obama to reach for the tool created by the framers for just such a situation. It is time for clemency.