Fifty years ago today, President Lyndon Johnson declared “unconditional war on poverty in America.” Narrowly defined, the war failed, in two ways. Most obviously, poverty still exists—indeed, the official poverty rate is only four percentage points lower today than it was then. Moreover, the government agency created to implement the War on Poverty--the long-forgotten Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO)--had lost Johnson’s active support by 1967, was actively undermined by President Richard Nixon (who briefly appointed the reactionary Howard Phillips to run it), and was finally put out of its misery by President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

But the official poverty numbers mask a substantial reduction in poverty attributable to government efforts, and although the OEO proved a short-lived failure, other poverty programs implemented under Johnson--Medicare, Medicaid, and, yes, food stamps--achieved measurable success.

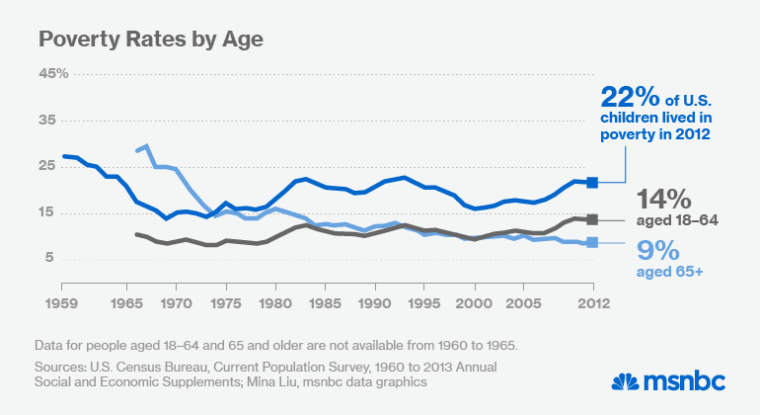

Even judging by the official poverty rate (currently $23,550 for a family of four), Johnson’s anti-poverty programs enjoyed initial success. The poverty rate for African-Americans dropped precipitously for the remainder of Johnson’s term. It evened off for the next 25 years, then dropped again under President Bill Clinton before rising slightly during the past decade. The poverty rate for the elderly dropped dramatically under Johnson and Nixon and, less dramatically, continues to do so. Overall, the official poverty rate declined significantly through Nixon’s first term before leveling off; since the 2008 crash it’s been rising.

None of these calculations include in-kind benefits through Medicare, Medicaid, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and none include the Earned Income Tax Credit, a program targeted to the working poor that was implemented under President Gerald Ford and greatly expanded under Reagan and Clinton. When these are factored in, the poverty rate has dropped nearly in half. That’s especially notable when you take into account that the 1996 welfare-reform bill, in addressing concerns that cash assistance to the jobless fostered dependency, cut the federal government’s cash-assistance caseload by 60%. Clinton really did end “welfare as we know it.” Unfortunately, the right responded by redirecting its fire toward non-cash programs that assist the working poor.

Government programs weren’t the only reason poverty declined. Sharon Parrott of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonprofit, points out a few other factors: high school graduation rates rose, families got smaller, and more women entered the workforce. (Less beneficial from an economic standpoint was a sharp rise in single parenthood.) But the much-reviled welfare state played a significant role in reducing poverty. Parrott observes that in 1967, government raised a mere 4% out of poverty, and today it raises more like 44%.

Ironically, it isn’t the government that’s failed the poor so much as the market economy. After 1979 the poor, defined as the bottom 20% in income distribution, saw no increase in their share of the nation’s pre-tax income (while the middle class saw its share decline). In absolute terms, pre-tax income rose two-fifths for the bottom 20%, compared to nearly three-fifths for the top 20%. For the top one percent, it more than tripled. Rather than pay workers a living wage, corporations like Wal-Mart and McDonalds guide them to government assistance programs. The majority of food-stamp recipients--and more than 60% of food-stamp recipients with children--have jobs. They just don’t get paid enough to eat. Whatever welfare dependence existed before 1996 has shifted from individuals to corporations.

Maybe it’s time the U.S. Chamber of Commerce declared its own War on Poverty by directing its members to raise wages for the working poor. But since that will never happen, the Obama administration proposes raising the minimum wage instead. Even better would be the removal of at least a few government obstacles to union organizing. But even Johnson, at the height of the Great Society—the most ambitious expansion of government power since the New Deal--lacked sufficient clout to achieve that.