This column is part of "The State of America," an msnbc.com series leading up to President Barack Obama’s 2015 State of the Union Address on Tuesday, Jan. 20. This is the state of the issues you care about, as told by organizations promoting social change.

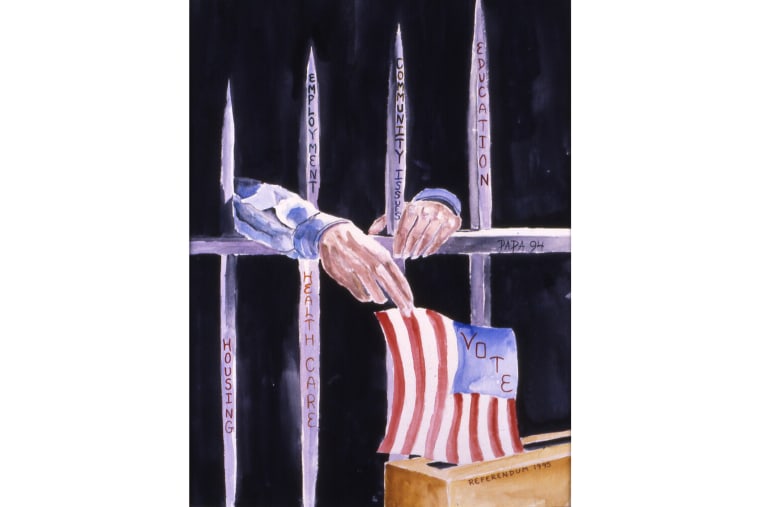

When President Obama delivers his State of the Union address on Jan. 20, he will be talking to two Americas: One of voters who will listen to his words to help form their political voices, and another group of “Americans” who, because of felony disenfranchisement, America’s longest standing form of voter suppression, have no political voice.

Harlem, New York, America’s most identifiable African-American community, has been vilified, gentrified and minimized because of this strategic and intentional dilution of its political strength. African-American communities across these United States have been decimated by 40 years of mass incarceration and will endure untold years of powerlessness due to felony disenfranchisement. Ending these injustices is what President Obama must prioritize in his last two years in office. The Harlems of America are calling for universal suffrage as a right, not a privilege; an inalienable right for all citizens.

"The Harlems of America are calling for universal suffrage as a right, not a privilege ..."'

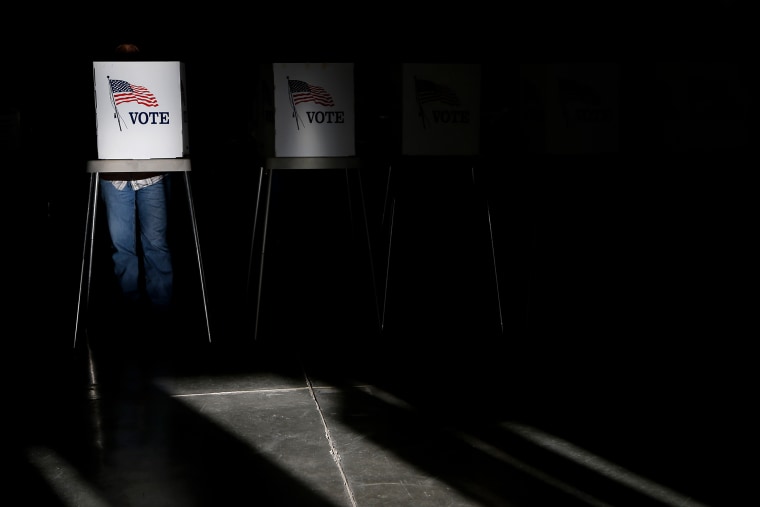

On Nov. 4, 2014, at 4:15 a.m., Larry White, 79, headed to the polls to serve as a poll monitor. White has held this responsibility during every election for the past six years. This time, however, things were a bit different. Larry left the site where he was working early so he could return to his Harlem neighborhood to vote … for the first time in his life. After more than 50 years of incarceration and community supervision, Larry’s constitutional right to vote was “restored” upon the termination of his parole. When All Things Harlem met Larry that morning, the natural question was, “How does it feel?”

“I feel like I count in some meaningful way for the first time in my life,” replied Larry.

Larry’s story is not unique. Today, one in 13 African-Americans are denied the right to vote. Felony disenfranchisement, the suppression of millions of black and brown votes, will continue to influence local, state and national elections in ways that maintain African-Americans’ status as second-class citizens.

The political impact of the unprecedented disenfranchisement rate in recent years is not insignificant. One study found that disenfranchisement policies likely affected the results of seven U.S. Senate races from 1970 to 1998, as well as the hotly contested 2000 Bush-Gore presidential election. If disenfranchised voters in Florida alone had been permitted to vote in 2000, Bush’s narrow victory “would almost certainly have been reversed.”

The 2014 midterm election results, where Republicans had massive gains both locally and nationally, were mired in voter suppression, including felony disenfranchisement. In three key Senate races in Georgia, Alaska and North Carolina, as well as in the Florida governor’s race, the number of disenfranchised felons was greater than the margin of victory. Not only does felony disenfranchisement contribute to the class and race bias in the electorate by primarily impacting low-income people and people of color, it often disenfranchises more voters than the margin of victory.

"This year, as we ... 'celebrate' the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, we must be mindful that there is unfinished business."'

This year, as we acknowledge the 50th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery marches and “celebrate” the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, we must be mindful that there is unfinished business. Mass incarceration and the new Jim Crow — specifically as manifested in felony disenfranchisement — have pushed back, if not nullified, the civil rights gained by the blood, sweat and tears of those who marched across this country in the '60s.

President Obama, the numbers are in, the research has been done, the issue has been well defined, and well publicized. What is needed now is the power of the White House.

Mr. President: Harlem, African-Americans across this Union, and people throughout the world are wondering: Is America democratic? The answer will frame your legacy.

Joseph “Jazz” Hayden is the CEO and founder of All Things Harlem and Campaign to End the New Jim Crow. Lewis Webb, Jr. is a program coordinator for American Friends Service Committee and Campaign to End the New Jim Crow. Both Hayden and Webb are advocates for criminal justice system reform and for prisoners' right to vote. All Things Harlem is a grassroots new media platform. The organization's mission is "to cover every aspect of the community life of the marginalized and voiceless at the base of the social structure in Harlem."