When Stephanie Nodd was released from prison on a warm Florida day back in November 2011, she confronted a world that was radically different than the one she left when she was put behind bars. After all, it had been 21 years.

Her mother had passed away. Her five children were now adults. She had grandchildren. Her once-rundown neighborhood in Mobile, Alabama now had nice restaurants, apartment buildings and businesses lining the streets. A black man was president.

It was difficult for Nodd to adjust, let alone find a job. The fact that she had a criminal record for her involvement in a crack cocaine conspiracy surely didn't help.

Nodd’s troubles started shortly after her 20th birthday when the single mother and high school dropout says she met a man named John, whom she helped for a little over a month setting up his business to sell drugs in return for money to provide for her children.

She eventually cut ties with John and moved to Boston to be with family. While there, Nodd was indicted on drug charges and returned home to take responsibility for her mistake, thinking she would avoid jail time because of her limited involvement. Nodd, then 23, was never caught with drugs and had no prior convictions. But under mandatory minimum sentencing laws, she received a 30-year sentence.

“I thought it was a joke,” Nodd told msnbc. “I didn’t think it was real. I didn’t want to live anymore.”

Times have changed since the 1980s' “war on drugs,” when states and the federal government passed laws requiring judges to hand down lengthy sentences to anyone caught or involved with illegal drugs, no matter the circumstances. Now, with crime rates in many urban areas down and the national prison population bursting at the seams, President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder are continuing to modify sentencing laws and reduce jail time for thousands of federal prisoners serving drug sentences. Critics of mandatory minimum laws say they disproportionately affect low-income and minority Americans.

“I didn’t need 20 years to learn my lesson. It would have taken me a month behind bars because it killed me to leave my kids,” said Nodd, now 47 years old. When she was sentenced, she was five months pregnant and had to give her child away to her family. She passed her time getting her GED, taking college courses, working in food services in prison, and exercising.

“I realized how quick you can go to prison but just how long it takes to get out," she said.

Because of the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s 2011 decision to reduce penalties for crack cocaine crimes, Nodd was able to get out of prison a few years early. And with many potential policy changes in the works, current and future inmates may not have to wait as long as she did.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Sentencing Commission unanimously voted to reduce sentencing guidelines for certain nonviolent drug offenses. The change would trim the average sentence for drug traffickers by approximately 11 months by lowering the drug sentencing guidelines two levels. Sentencing is based on “levels” depending on the quantity of controlled substance involved in a particular drug offense.

The new guidelines will go to Congress in the form of an amendment on May 1. Lawmakers will then have 180 days to make changes. If Congress does nothing, the amendment will go into effect on Nov.1. The change isn’t retroactive, so it wouldn’t affect those who have already been sentenced through mandatory minimums.

Deputy Attorney General James Cole announced this week that his department would broaden clemency criteria for drug offenders. Low-level, non-violent offenders without a significant criminal history will be made eligible to win early release from jail. They also must have spent at least 10 years behind bars and received a stricter sentence than they would have gotten if convicted for the same crime today.

Congress will also consider the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would cut in half mandatory 10 and 20 year terms for some lesser federal drug crimes. The law would give judges some discretion to impose sentences below the mandatory minimum. It passed the Senate Judiciary Committee in January and could be taken up by the full Senate as early as May.

Obama is clearly trying turn the tide and legacy of the old sentencing structure. The reforms would also be a real victory for Holder, whose tenure at Justice has been fraught with several controversies including the seizure of journalists' phone records and some officials at the Internal Revenue Service wrongly targeting conservative groups.

The times are changing

Public attitudes on criminal sentencing have been shifting for years. According to a national survey released this month the Pew Research Center, the majority of Americans want to significantly reduce the role of the criminal justice system in dealing with those who have used drugs. More than six in 10 Americans – 63% -- say that state governments moving away from mandatory prison terms for drug violations is a good thing. That’s a big change from 2001 when the survey found the public evenly divided over the issue.

Many states — both red and blue -- have also changed their laws to jail fewer Americans for lower level drug crimes.

Yet the National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys, which represents 5,400 federal prosecutors across the U.S., has vehemently opposed legislation supported by Holder to curb mandatory minimum drug sentences. In a letter to Democratic Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont and GOP Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa – the chair and ranking minority member of the Judiciary Committee, respectively -- the organization argued that the “current system works well in preserving public safety, is not broken, and should not be ‘fixed.’”

Among their arguments: mandatory minimums deter crime and help gain cooperation of defendants in lower-level roles; justice demands some type of consistency; and that there are already sufficient opportunities available to defendants through the current law to secure shorter sentences.

Other groups lobbying against sentencing reforms include the National Sheriffs’ Association, the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the National Narcotic Officers’ Associations’ Coalition.

Several leading Republicans have backed sentencing reform, including Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich and former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush.

The Smarter Sentencing Act also has bipartisan support, but not everyone is on board. Several Republican Judiciary Committee members did not vote in favor of the bill when it was voted out of the Committee 13-5 in January. They included Grassley, Sens. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, John Cornyn of Texas and Orrin Hatch of Utah.

Still, the act “has bipartisan support and is very much in play right now,” said Vanita Gupta, the American Civil Liberties Union’s legal director. “Right now we really just have to see what happens in the [Republican-led] House.”

Mary Price, who serves as the general counsel of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, said real federal reform started happening under Obama, in part due to the 2008 financial crisis.

“It spurred states to take a look at its sentencing and corrections policies, coupled with the budget crisis at the federal level,” she said.

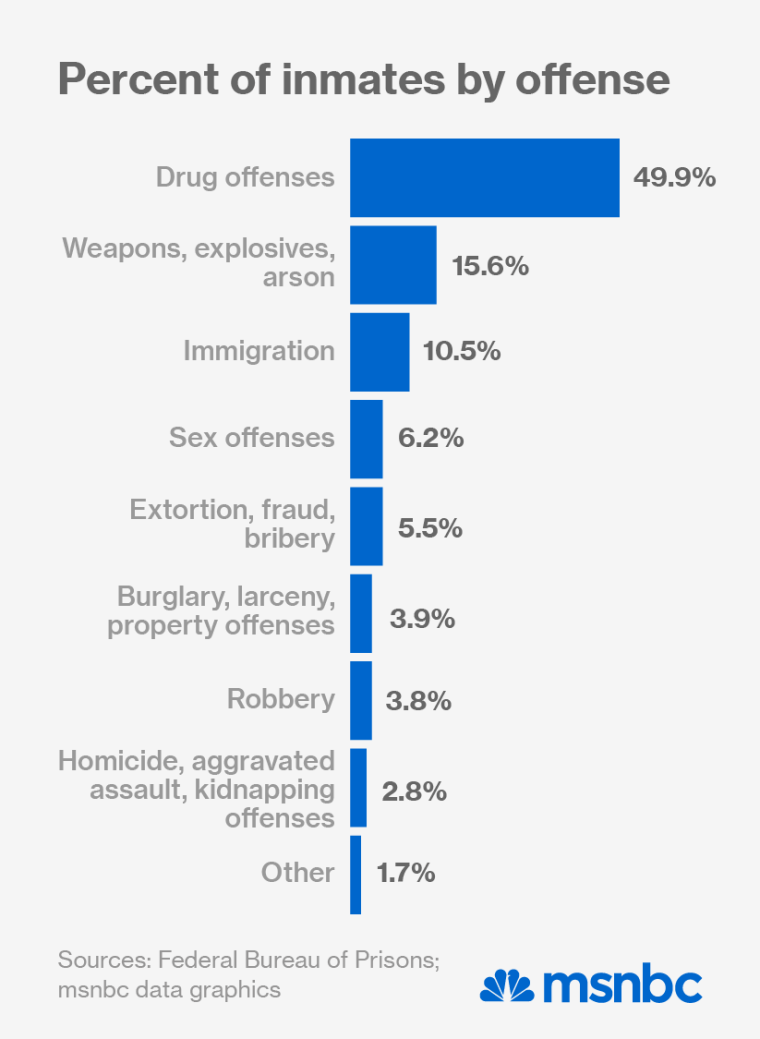

After all, one of every four Justice Department dollars is spent on locking up mostly non-violent offenders in federal prisons, according to tthe department's own data. Taxpayers spent almost $60 billion on prisons and jails in 2012 alone.

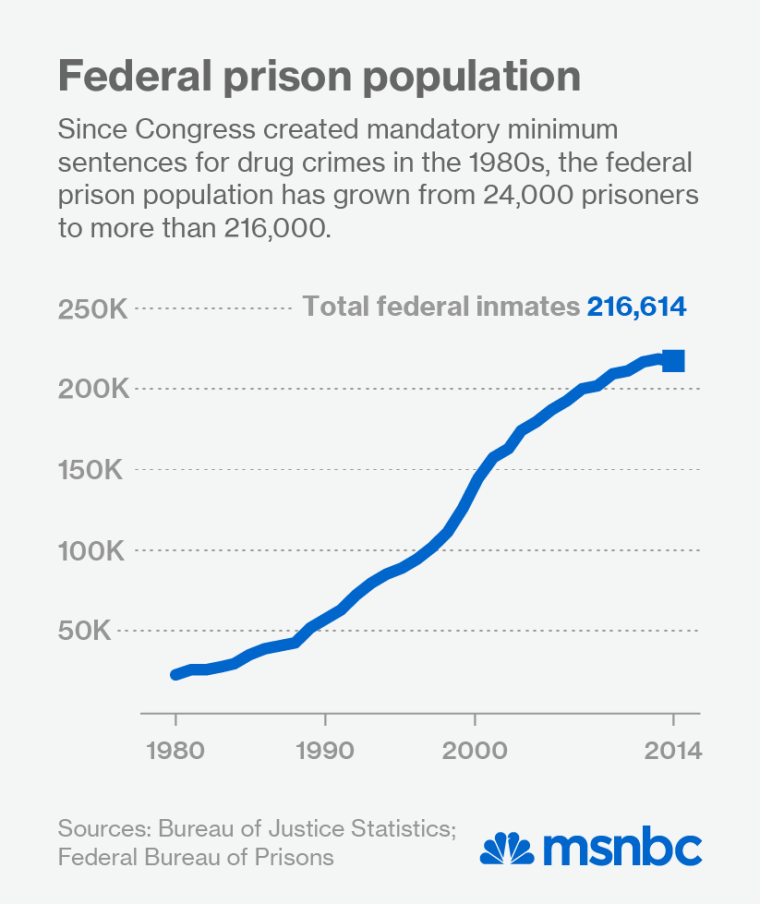

Since Congress created mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes in the 1980s, the federal prison population has grown from 24,000 prisoners to over 216,000, according to the federal Bureau of Prisons.

Price said she’s pleased policy makers want to make reforms but called the recent U.S. Sentencing Commission’s vote to reduce sentencing guidelines “modest.” But in the larger picture, Price said, “We’re very happy. It’s hard to see a downside here. I’d like to say we want more, but what we are seeing is pretty good.”

Gupta applauded the Justice Department for breathing new life into the clemency process. “Our federal sentencing laws have shattered families and wasted millions of dollars,” she said. “Too many people—particularly people of color—have been locked up for far too long for nonviolent offenses.”

That includes Nodd, who immediately knows exactly the amount of time she spent in jail. “21 years, 1 month and 24 days," she said.

When she came out of prison, her sister, best friend, and the daughter she bore while incarcerated were waiting for her. “Once that door opened, it was like a weight had been lifted off of me,” said Nodd, who will start a new job with Hertz later this month.

Although Nodd served the bulk of her long sentence, she’s optimistic the bills on the horizon will prevent first time offenders from missing out on life like she did. “It’s never too late. One day makes a difference out of somebody’s life. Even though I did this much time, I pray no one else does.”