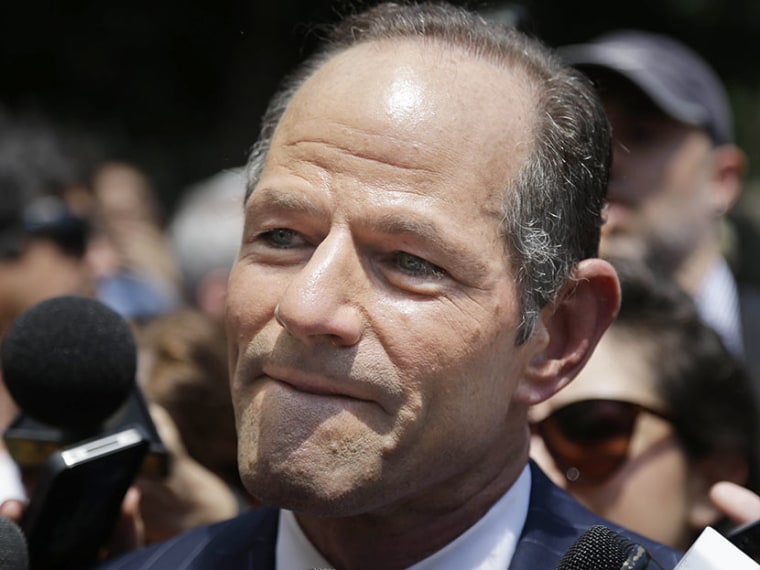

It would be foolhardy to suggest New York City voters shouldn’t think hard about turning over their comptroller’s office to an ex-governor once known to the Emperors Club VIP escort agency as Client-9. That’s a threshold question many voters won’t get past in deciding whether to support Eliot Spitzer’s return to politics.

For those who do, however, a more practical question awaits. Is the shareholder activism that Spitzer proposes using the job to espouse an effective tool for reforming corporate America?

Spitzer wants to be New York City comptroller mainly because the comptroller is in charge of the city’s five public-employee pension funds, whose combined assets total $140 billion.

The former governor--who made his name bird-dogging Wall Street corruption as state attorney general--laid out his vision for the job a year and a half ago in Slate magazine (where until earlier this year he wrote a column that turned out to be the first step in his political rehabilitation). “The current Occupy Wall Street could enlist a few savvy and courageous state and city comptrollers,” he wrote.

It could then rename itself “We Own Wall Street.” After acquiring a 5% stake in the major Wall Street firms that received bailouts or loan guarantees, We Own Wall Street could make two demands:

1.) Disclose all records of meetings with regulators since 2006.2.) Halt giving corporate funds to any entity, for-profit or nonprofit, that seeks to affect legislation or regulation.

That would certainly put a choke chain on the banks. “Ownership trumps regulation,” Spitzer likes to say, “as a way to change the way corporations behave.”

But what Spitzer envisions is more of a fantasy for regulators than shareholders, because a shareholder has to worry about maximizing return on investment.

Is a wholesale ban on all lobbying by banks truly a recipe for increasing bank profits? It’s hard to see how depriving them of lobbyists would do anything but lower their stock prices. Yet as comptroller, increasing banks’ stock prices would be Spitzer’s job as long as the pensions he oversaw were invested in them.

Would New York City voters care whether those pensions increased in value? Possibly not. They aren’t their pensions, after all. Voters might well be more interested in seeing banks and other corporations brought to heel, as they did when Spitzer was attorney general.

Would Spitzer himself care whether the pensions thrived? Not necessarily. The pensions he’d be in charge of might include his own, but Spitzer is independently wealthy and surely wouldn’t count on any annuity that New York City might provide him.

That’s the downside. But there’s a big upside too, and it’s a lot less theoretical.

As a practical matter, Spitzer is not going to gag the banks; I’d guess he’ll soon disavow that Slate column now that he’s a candidate for political office. Were Spitzer elected, its mere existence might cow the banks into lobbying less aggressively. But such an outcome could well benefit both stockholders and ordinary citizens. Prior to 2008 it was mainly the banks’ own recklessness (and resistance to regulation) that created the financial crisis. Less future meddling by banks in government policymaking might actually make banks more solvent in the future.

Academics disagree about the extent to which shareholder activism thus far has increased or decreased shareholder value, or indeed whether it has affected shareholder value at all. The studies are inconclusive because it’s hard to isolate individual factors that affect share price, and because the shareholder activism that has occurred thus far has been extremely modest. The most dramatic change, the “say on pay” provision in the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform law, allows shareholders to vote up or down on executive compensation--but the vote is nonbinding.

Accountable institutions tend in general to work better than unaccountable ones. A half-century ago economists considered it a given that stockholders had no say in the governance of corporations. That’s changed a little bit with the rise of “institutional investors”—mainly pension plans and money market funds—since the 1970s and 1980s. “There is no question,” says corporate governance expert Nell Minow, “that [growing shareholder power] made some difference.”

When she first got involved in the issue three decades ago, Minow said, O.J. Simpson sat on no fewer than five corporate boards (and sat on the audit committee for one of them). Today, boards are less packed with Hollywood and sports celebrities. “Say on pay” votes may be nonbinding, but they generate bad publicity that management doesn’t welcome, and not too long ago, the circulation of any reform proposal among more than ten shareholders required prior approval by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The current New York City Comptroller, John Liu, has already raised his office’s profile through shareholder activism—for example, by prodding two companies into adopting gender nondiscrimination policies.

A final reason not to fear Spitzer’s reformist tendencies, New York World points out,, is that his power would be more limited than it was as attorney general. (New York World is an excellent Web site operated by recent alumni of Columbia Journalism School and named after Joseph Pulitzer’s flagship newspaper.)

The city’s pensions are governed by an elaborate board structure that limits the comptroller’s oversight. Indeed, Minow observes, Spitzer would have far less power as city comptroller than he’d have as New York’s state comptroller, who is sole fiduciary of the pensions he oversees.

The current incumbent, Thomas DiNapoli, is up for re-election next year. Why isn’t Spitzer making a play for DiNapoli’s job instead? Probably because, given Spitzer’s lurid past, winning a statewide vote in New York would be much taller order than winning in New York City.

Whether Spitzer himself is morally fit to be city comptroller is a question only New York City voters can decide. But Spitzerism, despite a few potential pitfalls, might be worth a try.

Corrections: An earlier version of this column stated that O.J. Simpson sat on the compensation committee of a corporate board; it was an audit committee. Also, New York World website is run by Columbia Journalism School alumni, not students as originally written.